IL SETTECENTO E LO STILE

BAROCCHETTO O ROCOCÒ

Non è possibile parlare di mobili settecenteschi senza osservare che

in nessun’altra epoca il mobile di lusso si è tanto differenziato, anche

nella linea, dal mobile comune. Il Rococò avviluppa la linea usuale e la

camuffa sotto esuberanti motivi decorativi che compongono essi stessi

la struttura del mobile. Siamo nell’epoca di Charles Andrè Boulle,

creatore di uno stile e di un tipo di arredo rivestito di palissandro,

tartaruga, ebano, intarsiato di metalli e talvolta di placchette di

porcellana.

Il Settecento è anche il secolo del mobile intagliato, intarsiato, dipinto,

laccato o dorato, decorato con figurine, paesaggi e tralci di fiori.

L’epoca del Barocco ci ha lasciato la mobilia ricca creata in Francia,

nella culla di questo stile detto anche “Luigi XIV”, ma anche la sobria

mobilia dell’Inghilterra, quella pesante tedesca e l’esuberante spagnola

oltre agli arredi italiani, con i quali le scuole artigiane seppero tenere

testa alle esuberanze decorative curandone la linea. Possiamo trovare

questa mobilia a Venezia e nelle grandi città quali Milano, Genova e

Torino.

In questo secolo scompaiono bugnature, losanghe e riquadri cari al

primo Seicento, ma si affermano gli spigoli smussati o arrotondati, gli

intagli a curve e volute simmetriche, la linea a serpentina nelle facciate

di canterani e cantonali. Compare la “mossa inversa”, ossia una linea

sporgente ai lati e concava al centro. Nelle case signorili compaiono i

mobili a ribalta radicati, intarsiati, intagliati, con sculture dorate sulle

lesene. Le alzate hanno cimasa mossa e specchi di vetro.

Per i cassettoni ed altri mobili a tiretti e sportelli compare in Lombardia

il tipo di finitura con cornici e nervature verniciate in nero, che formano

un disegno a base di ricci e volute.

Mentre il Rococò, detto in francese “Rocaille”, abbandona ogni motivo

decorativo della Rinascenza e tende alla linea asimmetrica e capricciosa,

in Italia attorno al 1720 compare il Barocchetto che perdurò, insieme

con il Luigi XV d’importazione francese, fino all’ultimo quarto di

secolo.

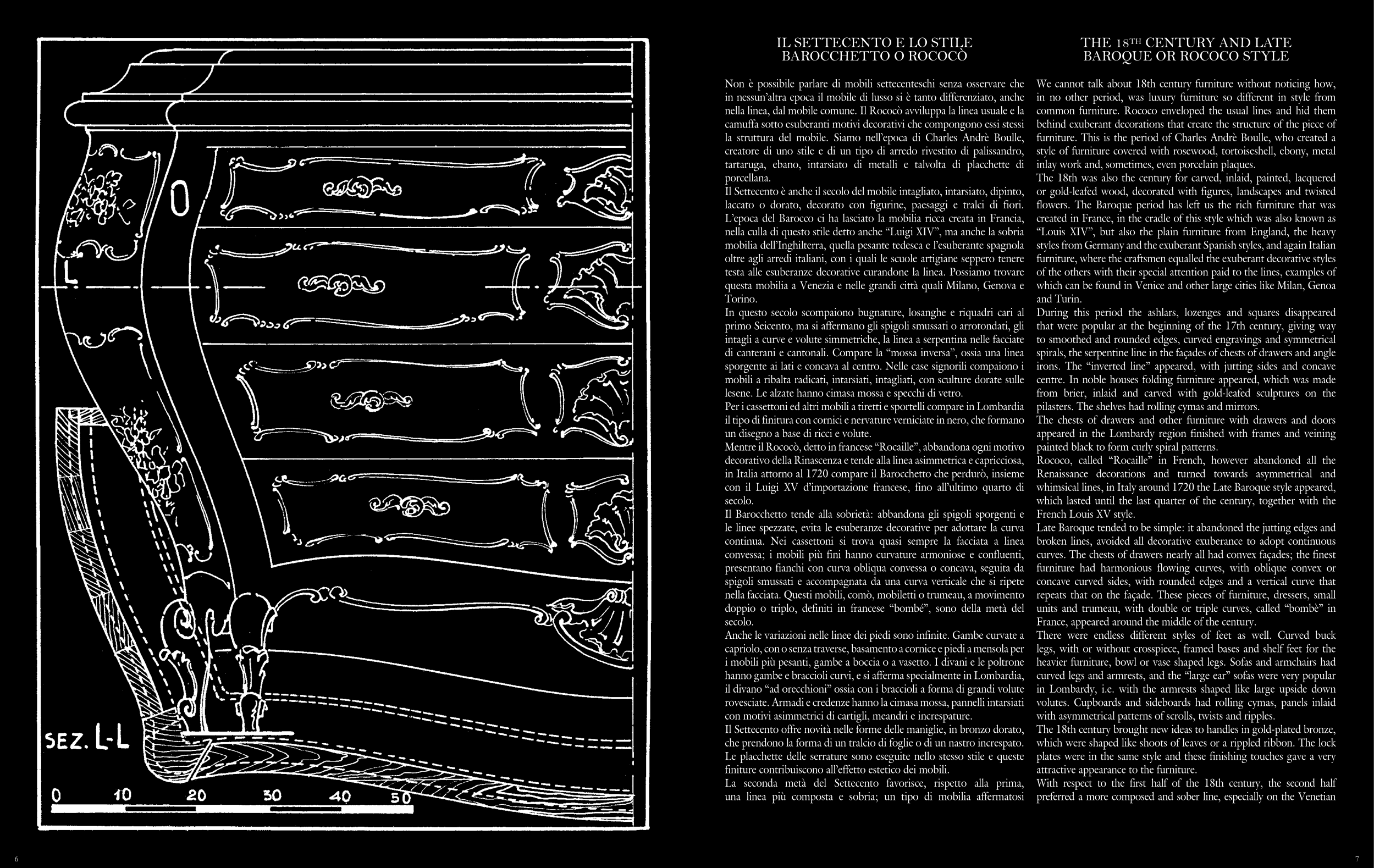

Il Barocchetto tende alla sobrietà: abbandona gli spigoli sporgenti e

le linee spezzate, evita le esuberanze decorative per adottare la curva

continua. Nei cassettoni si trova quasi sempre la facciata a linea

convessa; i mobili più fini hanno curvature armoniose e confluenti,

presentano fianchi con curva obliqua convessa o concava, seguita da

spigoli smussati e accompagnata da una curva verticale che si ripete

nella facciata. Questi mobili, comò, mobiletti o trumeau, a movimento

doppio o triplo, definiti in francese “bombé”, sono della metà del

secolo.

Anche le variazioni nelle linee dei piedi sono infinite. Gambe curvate a

capriolo, con o senza traverse, basamento a cornice e piedi a mensola per

i mobili più pesanti, gambe a boccia o a vasetto. I divani e le poltrone

hanno gambe e braccioli curvi, e si afferma specialmente in Lombardia,

il divano “ad orecchioni” ossia con i braccioli a forma di grandi volute

rovesciate. Armadi e credenze hanno la cimasa mossa, pannelli intarsiati

con motivi asimmetrici di cartigli, meandri e increspature.

Il Settecento offre novità nelle forme delle maniglie, in bronzo dorato,

che prendono la forma di un tralcio di foglie o di un nastro increspato.

Le placchette delle serrature sono eseguite nello stesso stile e queste

finiture contribuiscono all’effetto estetico dei mobili.

La seconda metà del Settecento favorisce, rispetto alla prima,

una linea più composta e sobria; un tipo di mobilia affermatosi

THE 18TH CENTURY AND LATE

BAROQUE OR ROCOCO STYLE

We cannot talk about 18th century furniture without noticing how,

in no other period, was luxury furniture so different in style from

common furniture. Rococo enveloped the usual lines and hid them

behind exuberant decorations that create the structure of the piece of

furniture. This is the period of Charles Andrè Boulle, who created a

style of furniture covered with rosewood, tortoiseshell, ebony, metal

inlay work and, sometimes, even porcelain plaques.

The 18th was also the century for carved, inlaid, painted, lacquered

or gold-leafed wood, decorated with figures, landscapes and twisted

flowers. The Baroque period has left us the rich furniture that was

created in France, in the cradle of this style which was also known as

“Louis XIV”, but also the plain furniture from England, the heavy

styles from Germany and the exuberant Spanish styles, and again Italian

furniture, where the craftsmen equalled the exuberant decorative styles

of the others with their special attention paid to the lines, examples of

which can be found in Venice and other large cities like Milan, Genoa

and Turin.

During this period the ashlars, lozenges and squares disappeared

that were popular at the beginning of the 17th century, giving way

to smoothed and rounded edges, curved engravings and symmetrical

spirals, the serpentine line in the façades of chests of drawers and angle

irons. The “inverted line” appeared, with jutting sides and concave

centre. In noble houses folding furniture appeared, which was made

from brier, inlaid and carved with gold-leafed sculptures on the

pilasters. The shelves had rolling cymas and mirrors.

The chests of drawers and other furniture with drawers and doors

appeared in the Lombardy region finished with frames and veining

painted black to form curly spiral patterns.

Rococo, called “Rocaille” in French, however abandoned all the

Renaissance decorations and turned towards asymmetrical and

whimsical lines, in Italy around 1720 the Late Baroque style appeared,

which lasted until the last quarter of the century, together with the

French Louis XV style.

Late Baroque tended to be simple: it abandoned the jutting edges and

broken lines, avoided all decorative exuberance to adopt continuous

curves. The chests of drawers nearly all had convex façades; the finest

furniture had harmonious flowing curves, with oblique convex or

concave curved sides, with rounded edges and a vertical curve that

repeats that on the façade. These pieces of furniture, dressers, small

units and trumeau, with double or triple curves, called “bombè” in

France, appeared around the middle of the century.

There were endless different styles of feet as well. Curved buck

legs, with or without crosspiece, framed bases and shelf feet for the

heavier furniture, bowl or vase shaped legs. Sofas and armchairs had

curved legs and armrests, and the “large ear” sofas were very popular

in Lombardy, i.e. with the armrests shaped like large upside down

volutes. Cupboards and sideboards had rolling cymas, panels inlaid

with asymmetrical patterns of scrolls, twists and ripples.

The 18th century brought new ideas to handles in gold-plated bronze,

which were shaped like shoots of leaves or a rippled ribbon. The lock

plates were in the same style and these finishing touches gave a very

attractive appearance to the furniture.

With respect to the first half of the 18th century, the second half

preferred a more composed and sober line, especially on the Venetian

7

6