94

95

no convinti che la bellezza vera si portasse appresso la giu-

stizia e il bene. Ciò che è veramente bello rappresenta so-

stanzialmente una specie di armonia disarmonica che non

può avere a che fare con il male. È la più grande realizzazio-

ne della nostra umanità, delle nostre migliori capacità, del

nostro più elevato modo di ragionare. La bellezza vera si

lega inestricabilmente alla giustizia e al bene. Il bel logos, il

bel modo di ragionare signifi ca quindi automaticamente

comportamento giusto, azioni virtuose. Di fronte a queste

due certezze – potenza dell’eros e bellezza/bene – Platone

that real beauty was close to justice and good. What is really

beautiful basically represents a kind of discordant harmony

that can have nothing whatsoever to do with evil. It is the

greatest achievement of our humanity, of our best capacities,

of our most elevated way of thinking. Real beauty is inextri-

cably linked to justice and good. The bel logos, the good way

of reasoning therefore automatically means the right behav-

iour, virtuous actions. In front of these two certainties – the

power of love and beauty/goodness – Plato did nothing but

advance one step to put them suitably together. In the end, the

If young people grow up in a beautiful city they will only

be able love that beauty, try to adapt to it and therefore will

grow up capable of reasoning in the best possible way and

to behave themselves in the fairest possible way.

non fece altro che avanzare di un passo per metterle adegua-

tamente assieme. La chiave del suo progetto educativo sta

tutta qui, in fondo. Legare la passione dei giovani con la bel-

lezza. Se i giovani crescono in una città bella (dunque giu-

sta) non potranno che amare quella bellezza, tentare di uni-

formarsi a essa e dunque cresceranno capaci di ragionare

nella maniera più bella e di comportarsi in maniera giusta.

Ma come educare i giovani a una passione che riesca a

tenderne completamente l’animo verso la bellezza? Questo

fu il grande dilemma con cui fece i conti Platone e che lo

spinse alla condanna di Omero di cui abbiamo parlato.

Le cose stavano così: Platone sapeva che la grande emo-

tività degli eroi omerici poteva incarnarsi in comportamenti

del tutto opposti. Lo snodo dell’anima iraconda e desiderosa di

gloria che caratterizza tutti i personaggi raccontati nei poemi

può tendere verso grandi obiettivi ma può anche precipitare

nella sua più nefasta e mortifera incarnazione. Esistono “calde

lacrime”, vitali, di eroi presi da un’ira che li spinge a difendere

i loro ideali e a lottare per ciò che ritengono giusto. Esiste il

“gelido pianto” di eroi presi da un’ira che diventa rancore sor-

do e li sprofonda verso la miseria dell’egoismo e della presun-

zione. Platone sapeva bene che quell’enorme potentissima pas-

sione, se slegata dal bello e dal bene, rischiava di risucchiare i

giovani nelle sabbie mobili del vizio. Lo scrisse in maniera

esplicita, nella La Repubblica, probabilmente pensando a Alci-

key to his enlightening project lies here. Bind the passion of

young people to beauty. If young people grow up in a beauti-

ful city (and therefore right and fair) they will only be able

love that beauty, try to adapt to it and therefore will grow up

capable of reasoning in the best possible way and to behave

themselves in the fairest possible way.

How to educate young people on a passion that is able

to stretch the soul towards beauty? This was the greatest di-

lemma that Plato faced and that led him to the conviction of

Homer that we have spoken about.

It was like this: Plato knew that the great emotivity of

homeric heroes could be incarnated into completely opposite

behaviours. The turning point of the irascible and glory seek-

ing soul that characterizes all the characters in poems can be

stretched towards great objectives but can also deteriorate in

its most inauspicious and deadliest incarnation. There “hot

tears”, vital, from heroes so enraged that they are driven to

defend their ideals and to fi ght for what they believe to be

right. There is an “icy cry” by heroes so enraged that it be-

comes dull resentment and sinks them into the misery of self-

ishness and conceit. Plato knew only too well that, that enor-

mous and extremely powerful passion, if unleashed by

beauty and right, threatened to suck young people into the

quicksand of vice. He wrote about this explicitly in La Re-

pubblica, probably thinking about Alcibiades, the young

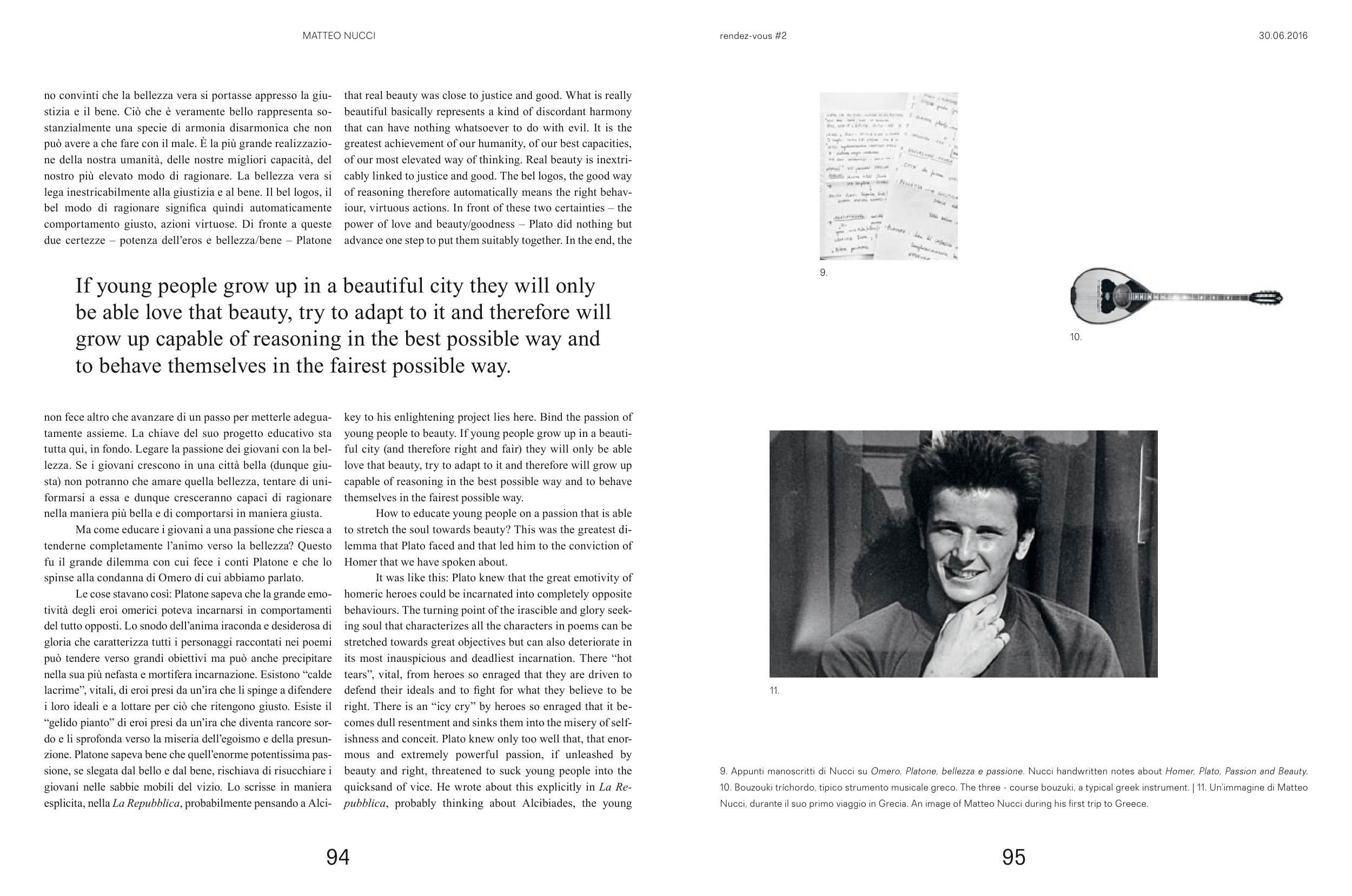

11.

9.

10.

MATTEO NUCCI

9. Appunti manoscritti di Nucci su Omero, Platone, bellezza e passione. Nucci handwritten notes about Homer, Plato, Passion and Beauty.

10. Bouzouki tríchordo, tipico strumento musicale greco. The three - course bouzuki, a typical greek instrument. | 11. Un’immagine di Matteo

Nucci, durante il suo primo viaggio in Grecia. An image of Matteo Nucci during his first trip to Greece.

30.06.2016

rendez-vous Δ2