90

91

sato alla storia come una grande utopia, ossia il non-luogo

dei sogni irrealizzabili. Ma quando il fi losofo si dedicò al

dialogo che noi tutti conosciamo come La Repubblica, non

erano sogni quelli che coltivava bensì progetti. Era ormai

ben noto nella sua Atene ma anche in Sicilia e soprattutto a

Siracusa dove era andato a tentare i primi accenni del suo

esperimento politico. Tutti sapevano che se aveva aperto una

scuola non era per formare ragazzi capaci solo di contempla-

re le stelle. La grande domanda a cui tutti i fi losofi avevano

cercato di rispondere – ossia “come vivere bene?”, “come es-

sere felici?” – si traduceva per Platone nella questione politi-

ca per eccellenza, perché legata alla realizzazione della po-

or namely not the place of pipe dreams. But when the philos-

opher devoted himself to the dialogue that all of us know as

La Repubblica, he did not cultivate dreams but projects. He

was now well-known in his home city of Athens but also in

Sicily and above all in Syracuse where he had gone to try the

fi rst allusions of his political experiment. Everybody knew

that if he had opened a school it was not for training boys to

gaze upon the stars. The big question to which all philoso-

phers had tried to seek the answer to – or rather “how to live

well?”, “How to be happy” – resulted in the political ques-

tion par excellence for Plato because it was connected to the

creation of polis, or rather, a fair policy for the creation of a

But let’s start at the beginning and look at the fi rst books.

Here Plato offers a picture of reform of the literature of

the time to educate young people mainly on two virtues:

moderation and courage.

lis, ossia una politica giusta per la realizzazione di una polis

in cui dominasse la giustizia. E per fare questo il primo irri-

nunciabile sforzo riguardava la formazione dei giovani, l’e-

ducazione, la cosiddetta paideia. Fu nell’ambito di questo

grande tentativo che il fi losofo si lanciò nella sua battaglia

contro Omero. Se allora Omero era considerato il poeta per

eccellenza, il maestro dell’Ellade, colui che aveva sfornato

poemi capaci di costituire una specie di grande enciclopedia

dei saperi, era proprio Omero il primo obiettivo a cui dedi-

carsi, il maestro da sostituire, il maestro a cui sostituirsi.

Nella La Repubblica sono due i luoghi in cui noi assi-

stiamo alla grande battaglia platonica per la supremazia pai-

deutica. Fra i dieci libri che scandiscono il dialogo, il II e il

III sono i più famosi. Ma anche nell’ultimo libro Platone tor-

na sulla questione. Ciò che colpisce un lettore attento è che

in entrambi i luoghi, mentre combatte Omero, Platone si

confronta paradigmaticamente con l’eroe senza volto, l’eroe

in lacrime. Ma cominciamo dall’inizio e guardiamo ai primi

libri. Qui Platone offre un quadro di riforma della letteratura

del tempo per educare i giovani principalmente a due virtù:

la temperanza e il coraggio. Si tratta di due virtù entrambe

decisive ma quella fondamentale per ragazzi che dovranno

affrontare ogni pericolo e ogni sfi da pur di difendere la nuo-

polis in which justice dominated. In order to do this the fi rst

fundamental concentration regarded training and educating

the young people, education the so-called paideia. It was

within this context that the philosopher launched his battle

against Homer. Then if Homer was considered the poet par

excellence, the Master of Hellas who had created poems able

to build a type of great encyclopedia of knowledge, it was

then Homer the fi rst objective to dedicate himself to, the

master to substitute, the master to be substituted with.

There are two places in La Repubblica in which we

witness the great Platonic battle for paideutic supremacy.

The most famous books amongst the ten that spell out the

dialogue, Books II and III are the most famous. But Plato

returns to the issue also in the last book. What strikes an at-

tentive reader is that in both places, when challenging Hom-

er, Plato confronts himself paradigmatically with the hero

without a face, the hero in tears. But let’s start at the begin-

ning and look at the fi rst books. Here Plato offers a picture of

reform of the literature of the time to educate young people

mainly on two virtues: moderation and courage. They are

both decisive virtues but the fundamental one for the young

ones who will have to face every danger and every challenge

in order to defend the new city is courage. Plato takes this

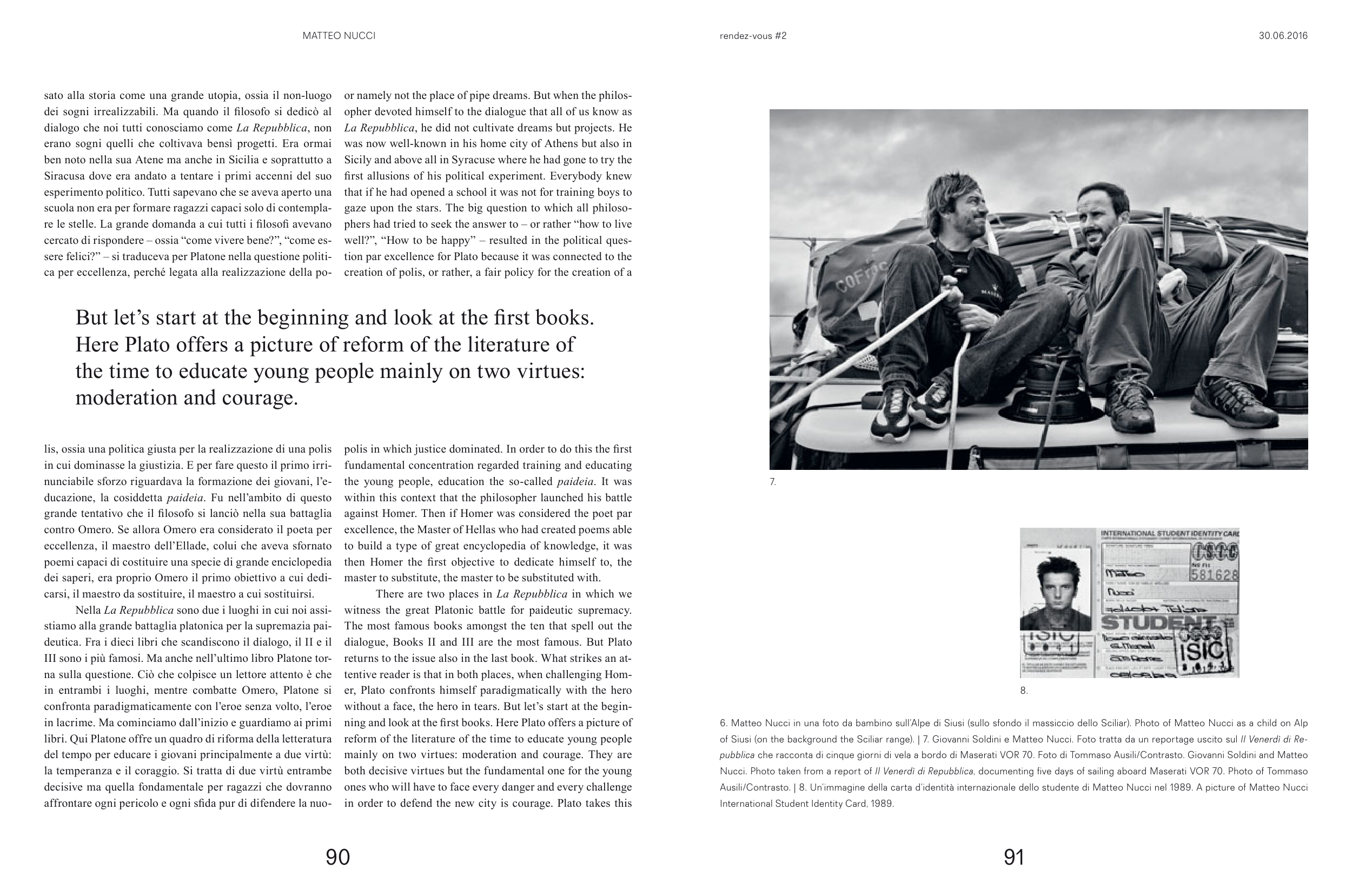

7.

8.

MATTEO NUCCI

6. Matteo Nucci in una foto da bambino sull’Alpe di Siusi (sullo sfondo il massiccio dello Sciliar). Photo of Matteo Nucci as a child on Alp

of Siusi (on the background the Sciliar range). | 7. Giovanni Soldini e Matteo Nucci. Foto tratta da un reportage uscito sul Il Venerdì di Re-

pubblica che racconta di cinque giorni di vela a bordo di Maserati VOR 70. Foto di Tommaso Ausili/Contrasto. Giovanni Soldini and Matteo

Nucci. Photo taken from a report of Il Venerdì di Repubblica, documenting five days of sailing aboard Maserati VOR 70. Photo of Tommaso

Ausili/Contrasto. | 8. Un’immagine della carta d’identità internazionale dello studente di Matteo Nucci nel 1989. A picture of Matteo Nucci

International Student Identity Card, 1989.

30.06.2016

rendez-vous Δ2