86

87

ira con cui Achille si allontana dalla guerra augurandosi che

il rivale sia destinato a pagarla, si trasforma subito nel nostro

grande personaggio in lacrime. Achille se ne va “in riva al

mare canuto” (I, 350), si siede, implora la madre e scoppia a

piangere. Il liquido lacrimale si confonde nel liquido del

mare. Teti, fi glia del Vecchio del Mare, una Nereide, divinità

marina, liquida, polimorfa è in ascolto. Le parole di Achille

attraversano l’aria e l’acqua.

“Molto implorava la madre, stendendo le mani: / «Madre, poi che

mi generasti a vivere breve vita, / gloria almeno dovrebbe darmi

l’Olimpio / Zeus, che tuona sui monti; e invece per nulla m’onora. /

Ecco, il fi glio d’Atreo strapotente, Agamennone, / m’offende, m’ha

preso e si tiene il mio dono, me l’ha strappato!» / Diceva così ver-

sando lacrime: l’udì la dea madre / seduta negli abissi del mare, vi-

cino al padre vegliardo: / subito emerse dal mare canuto, come neb-

bia, / e si mise a sedere vicino a lui che piangeva, / lo carezzò con la

mano e disse parole, diceva: / «Creatura mia, perché piangi? Che

pena ha colpito il tuo cuore? / parla, non la nascondere, perché tutti

e due la sappiamo!» / E a lei, con grave gemito, Achille piede rapido

disse” (I, 351-364).

I singhiozzi che uniscono madre e fi glio sono il sug-

gello dell’inizio del poema. E sono anche il suggello della

sua conclusione. In cui la madre viene sostituita da un padre.

Non è il padre di Achille, ma il padre di Ettore. Sappiamo

tutti cosa va a fare, il vecchio Priamo, di notte, scortato in-

consapevolmente da Ermes, attraversando il campo nemico.

Il corpo del suo fi glio migliore è steso nella tenda del ragaz-

zo che glielo ha ucciso. Qui, noi lettori di oggi ci aspettiamo

il dolore più atroce, quello di un padre che ha perso il fi glio,

e veniamo invece sorpresi dal dolore speculare, quello di un

fi glio che intravede, in una lampeggiante anticipazione, il

dolore del suo stesso padre quando, fra poco, Achille non

sarà più fra i mortali. È una scena che nessuno ha mai saputo

replicare. Achille osserva Priamo, re dei nemici, padre del

più acerrimo nemico, e in lui vede solo un vecchio che ha

perso il fi glio e, attraverso di lui, vede il vecchio Peleo, suo

padre, che non riabbraccerà più il fi glio. Priamo, a sua volta,

osserva Achille, il più atroce nemico, ma in lui non vede

l’uomo che ha massacrato Ettore, bensì l’eroe giovane, lumi-

noso, forte della sua fragilità, l’eroe che è stato il suo miglio-

re fi glio. Sulla scena, alla fi ne dell’Iliade, incontriamo sem-

plicemente un padre e un fi glio. Del resto, questo è il poema

dove “ci sono soltanto uomini che soffrono, guerrieri che

combattono, trionfano o soccombono” come scrisse Rachel

Bespaloff, vincenti e perdenti solo temporaneamente, dun-

que. Non più nemici. Solo un padre e un fi glio che si abbrac-

ciano e insieme piangono:

“Immersi entrambi nel ricordo, l’uno per Ettore massacratore /

piangeva a dirotto prostrato ai piedi di Achille, / mentre Achille

piangeva suo padre, ma a tratti / anche Patroclo: il loro lamento

echeggiava per la casa. / Ma quando il divino Achille fu sazio di

pianto, / gli svanì quella voglia dal corpo e dal cuore, / s’alzò di

scatto dal seggio, sollevò per la mano il vecchio, / mosso a pietà

dalla sua testa bianca, dal suo mento bianco, / e articolando la voce,

gli diceva parole che volano” (XXIV 509-17).

Quel che accade nell’Odissea è assolutamente specu-

lare. All’inizio del poema, quando gli dèi lasciano la scena

agli umani, ci sono un fi glio e una madre, Telemaco e Pene-

lope, che immediatamente ci si rivelano per una caratteristi-

ca comune: sono spesso in lacrime. A noi però importa piut-

tosto la prima comparsa del grande eroe protagonista, le cui

gesta e i cui patimenti danno il nome al poema. Dobbiamo

aspettare il V libro per vedere Odisseo, ma il lettore (e l’a-

scoltatore di un tempo) sa già dove trovarlo e in che posizio-

ne. I cantori omerici non usano mai lo strumento della su-

spense. Semmai anticipano e dilatano e così impongono a

chi si confronta con il poema la possibilità di un cambia-

mento interiore. Di Odisseo abbiamo già sentito parlare in

tre occasioni. Prima, quando Atena lo ha raccontato a Zeus,

poi quando Menelao ha rievocato quel che gli raccontò Pro-

vowing his wrath to Agamenmon. This famous rage with

which Achille moves away from the war hoping that his rival is

destined to pay for it, immediately transforms our great char-

acter to tears. Achille goes “by the hoary sea” (I, 350), sits

down, implores his mother and bursts into tears. The tears

mingle with the sea water. Thetis, daughter of the Old Man of

the Sea, a Nereid, a marine divinity, fl uid, a polimorfa is listen-

ing. Achille’s words pass through the air and the water.

“Stretching out his hands, he cried aloud to his mother: / «Mother,

since you gave me life - if only for a while - Olympian / Zeus, high

thunderer, should give me due honour. / But he doesn’t grant me

even slight respect. For wide-ruling Agamemnon, Atreus’ son / has

shamed me, has taken away my prize, appropriated for its own

use!» / As he said these words he wept: His divine mother heard him

/ from deep within the sea, where she sat by her old father: / quickly

she rose up moving out of the grey water, like an ocean mist, / and

sat down next to him, as he wept / She stroked him and then said: /

«My child, why are you weeping? What sorrows weigh heavy on

your heart? Tell me, don’t hide from me what’s on your mind so we

will both know!» / With a deep groan, swift footed Achilles then

said” (I, 351-364).

The sobs that unite mother and son are the seal of the

beginning of the poem. And they are also the seal of its con-

clusion. In which the mother is substituted by a father. It is

not Achille’s father but Hector’s. We all know what he gets

up to, old Priam, at night, escorted unwittingly by Hermes,

crossing over enemy lines. The body of his preferable son is

lying in the tent of the boy who killed him. At this point,

readers of today expect the most excruciating pain, that of a

father who has lost his son, and we are rather surprised by

the specular pain, that of a son who sees, in a fl ashing fore-

taste, the pain of his own father, when in a little while, Achil-

les will no longer be among mortals. It is a scene that no-else

has ever known how to replicate. Achilles observes Priam,

the king of all enemies, the father of his fi ercest enemy, and

in him sees only the old man who has lost his son and,

through him, sees his father, old Peleo, who will not embrace

his son again. Priam, in turn, observes Achilles, the most

atrocious enemy, but doesn’t see the man who massacred

Hector, but rather the young hero, bright, strong in his own

fragility, the hero who was his preferable son. In the scene,

at the end of Iliad, we simply meet a father and a son. After

all, this is the poem where “there are only men who suffer,

warriors who fi ght, triumph or succumb” as Rachel Be-

spaloff wrote, therefore victorious and defeated only tempo-

rarily. No longer enemies. Only a father and a son who em-

brace and weep together:

“Both were lost in memory, one for man-killing Hector / and wept

aloud, at Achilles feet, / while Achilles wept for his father / and for

Patroclus: the sound of their lament fi lled the house. / But when

Achilles was satiated with weeping / and the force of grief was

spent, / he rose instantly from his chair, and raising the old man by

the arm, / moved in pity on his white beard and hair / and spoke

eloquently to him, saying words that drift” (XXIV 509-17).

What happens in Odyssey is absolutely specular. At

the beginning of the poem, when the Gods leave the scene to

the humans, there is a mother and a son, Telemachus and Pe-

nelope, who immediately reveal a common feature: they are

often in tears. It is more relevant to us the fi rst appearance of

the great hero, the protagonist, whose actions and whose suf-

ferings give the name to the poem. We have to wait until

Book V to see Odysseus, but the reader (and at one time the

listener) already knows where to fi nd him and in what posi-

tion. The Homeric cantors never use suspense. If anything

they anticipate and expand thus imposing those who confront

themselves with the poem the possibility of an inner change.

We have already heard of Odysseus on three occasions. The

fi rst, when Athena talked about him to Zeus, then when Me-

nelaus recalled what Proteus, the Old Man of the Sea, told

him. And fi nally when the cantors explained his whereabouts

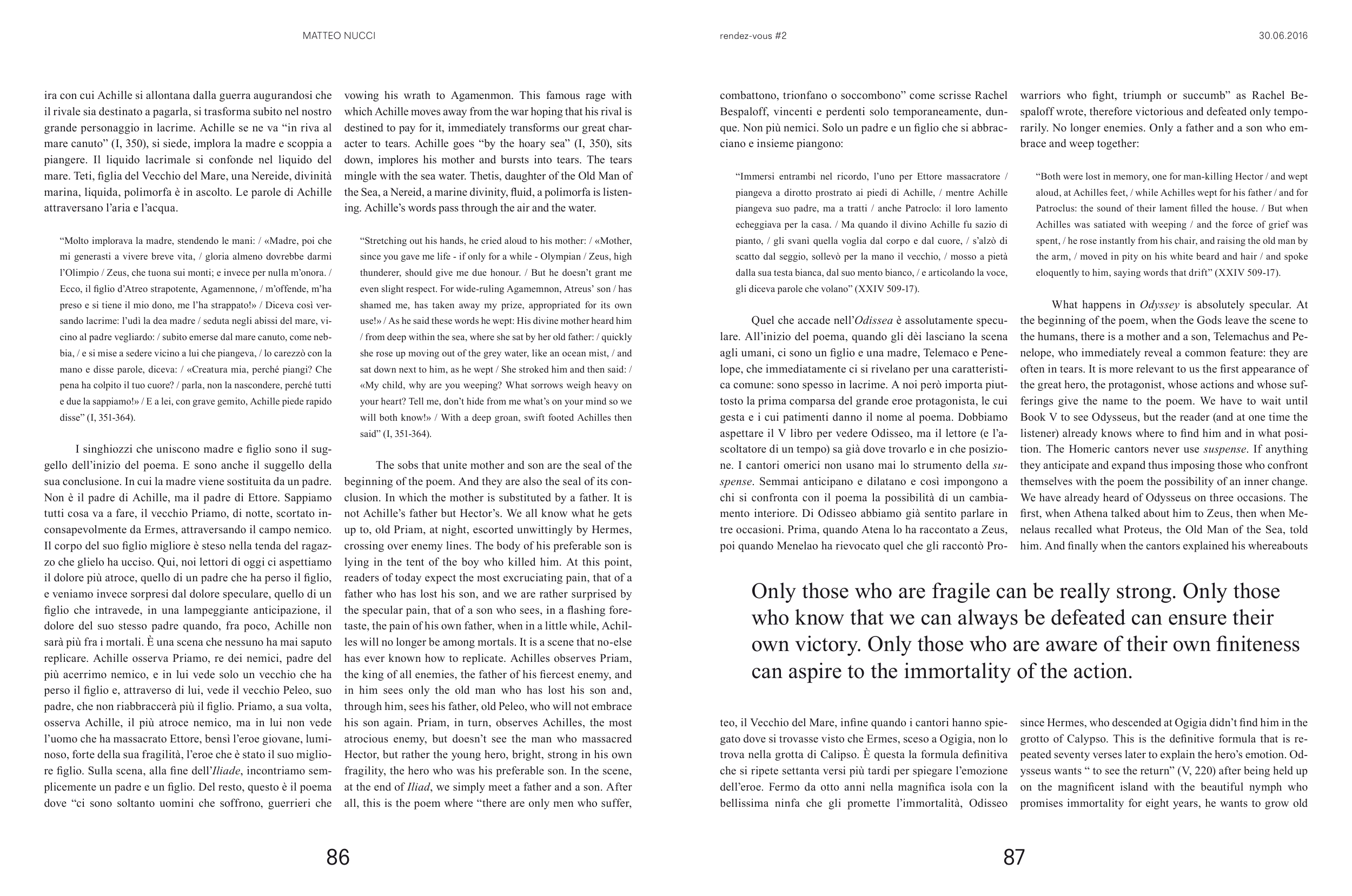

Only those who are fragile can be really strong. Only those

who know that we can always be defeated can ensure their

own victory. Only those who are aware of their own fi niteness

can aspire to the immortality of the action.

teo, il Vecchio del Mare, infi ne quando i cantori hanno spie-

gato dove si trovasse visto che Ermes, sceso a Ogigia, non lo

trova nella grotta di Calipso. È questa la formula defi nitiva

che si ripete settanta versi più tardi per spiegare l’emozione

dell’eroe. Fermo da otto anni nella magnifi ca isola con la

bellissima ninfa che gli promette l’immortalità, Odisseo

since Hermes, who descended at Ogigia didn’t fi nd him in the

grotto of Calypso. This is the defi nitive formula that is re-

peated seventy verses later to explain the hero’s emotion. Od-

ysseus wants “ to see the return” (V, 220) after being held up

on the magnifi cent island with the beautiful nymph who

promises immortality for eight years, he wants to grow old

MATTEO NUCCI

30.06.2016

rendez-vous Δ2