6

7

M&C 13

#BuildingArchitecture

Chapeau les artistes!

by Jean Nouvel

Exterior and interior

views of the Musée

du quai Branly,

Paris, 2007.

Fondation Cartier

pour l’art contemporain,

Paris, 1994.

A quiet understanding

by Renzo Piano

Jerome L. Greene

Science Center

Columbia University,

New York, 2017.

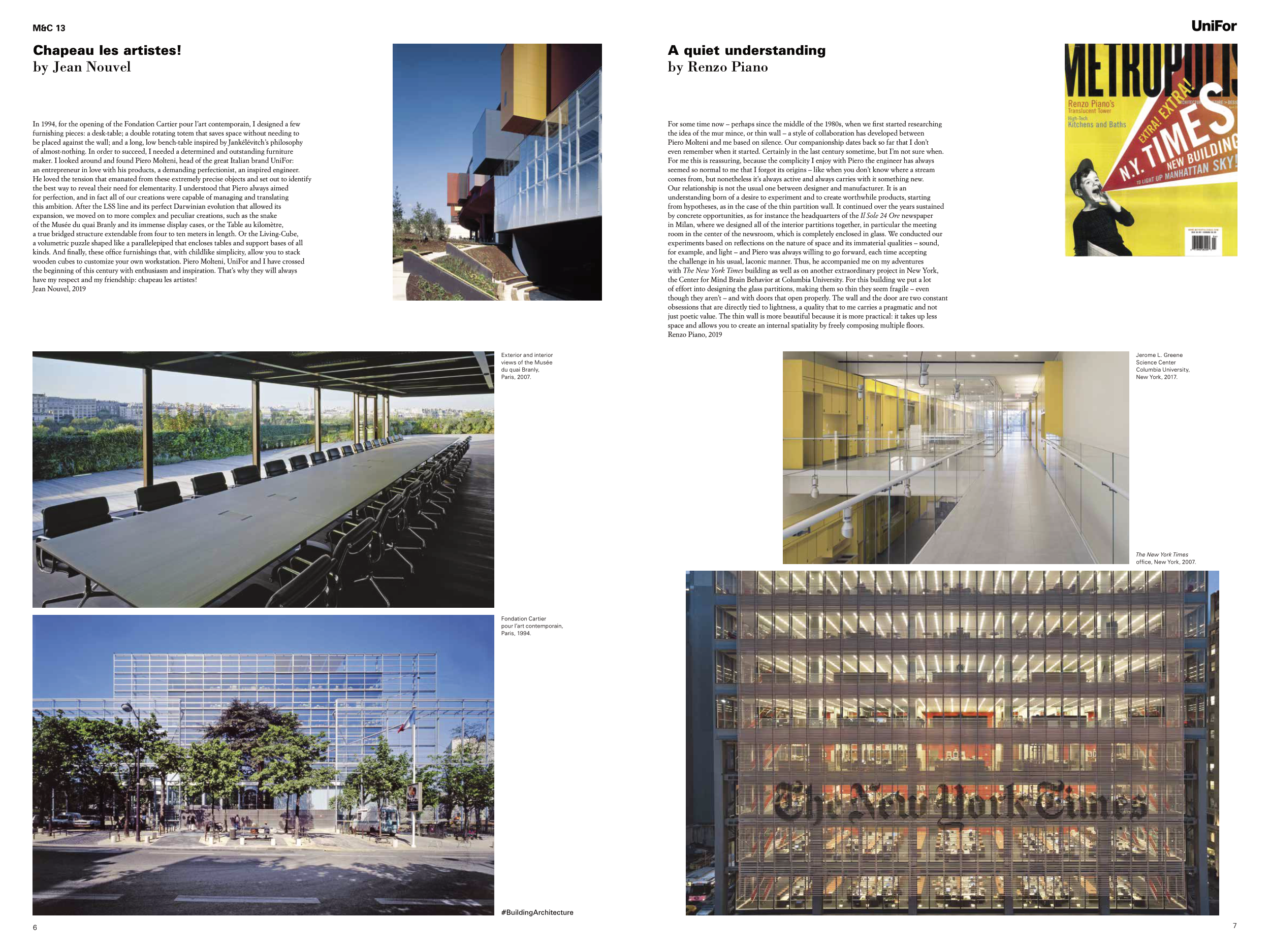

The New York Times

office, New York, 2007.

In 1994, for the opening of the Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain, I designed a few

furnishing pieces: a desk-table; a double rotating totem that saves space without needing to

be placed against the wall; and a long, low bench-table inspired by Jankélévitch’s philosophy

of almost-nothing. In order to succeed, I needed a determined and outstanding furniture

maker. I looked around and found Piero Molteni, head of the great Italian brand UniFor:

an entrepreneur in love with his products, a demanding perfectionist, an inspired engineer.

He loved the tension that emanated from these extremely precise objects and set out to identify

the best way to reveal their need for elementarity. I understood that Piero always aimed

for perfection, and in fact all of our creations were capable of managing and translating

this ambition. After the LSS line and its perfect Darwinian evolution that allowed its

expansion, we moved on to more complex and peculiar creations, such as the snake

of the Musée du quai Branly and its immense display cases, or the Table au kilomètre,

a true bridged structure extendable from four to ten meters in length. Or the Living-Cube,

a volumetric puzzle shaped like a parallelepiped that encloses tables and support bases of all

kinds. And finally, these office furnishings that, with childlike simplicity, allow you to stack

wooden cubes to customize your own workstation. Piero Molteni, UniFor and I have crossed

the beginning of this century with enthusiasm and inspiration. That’s why they will always

have my respect and my friendship: chapeau les artistes!

Jean Nouvel, 2019

For some time now – perhaps since the middle of the 1980s, when we first started researching

the idea of the mur mince, or thin wall – a style of collaboration has developed between

Piero Molteni and me based on silence. Our companionship dates back so far that I don’t

even remember when it started. Certainly in the last century sometime, but I’m not sure when.

For me this is reassuring, because the complicity I enjoy with Piero the engineer has always

seemed so normal to me that I forgot its origins – like when you don’t know where a stream

comes from, but nonetheless it’s always active and always carries with it something new.

Our relationship is not the usual one between designer and manufacturer. It is an

understanding born of a desire to experiment and to create worthwhile products, starting

from hypotheses, as in the case of the thin partition wall. It continued over the years sustained

by concrete opportunities, as for instance the headquarters of the Il Sole 24 Ore newspaper

in Milan, where we designed all of the interior partitions together, in particular the meeting

room in the center of the newsroom, which is completely enclosed in glass. We conducted our

experiments based on reflections on the nature of space and its immaterial qualities – sound,

for example, and light – and Piero was always willing to go forward, each time accepting

the challenge in his usual, laconic manner. Thus, he accompanied me on my adventures

with The New York Times building as well as on another extraordinary project in New York,

the Center for Mind Brain Behavior at Columbia University. For this building we put a lot

of effort into designing the glass partitions, making them so thin they seem fragile – even

though they aren’t – and with doors that open properly. The wall and the door are two constant

obsessions that are directly tied to lightness, a quality that to me carries a pragmatic and not

just poetic value. The thin wall is more beautiful because it is more practical: it takes up less

space and allows you to create an internal spatiality by freely composing multiple floors.

Renzo Piano, 2019