58

59

La parola materiali deriva da materia, ha la stessa radice

fisica, solida, concreta. Grave. Ma è termine più specifico,

differenziato, il plurale indica che siamo già in presenza di

molte varianti, di un mondo studiato e classificato ancor

prima di Linneo. Istintivamente, a parlare di materiali,

attiviamo nel nostro cervello una divisione netta che ci porta

a distinguere le cose materiali dalle cose immateriali, le cose

concrete da quelle astratte; le cose umane, terrene, da quelle

divine, filosofiche, speculative. Un dualismo che separa la

sfera dei sensi da quella del pensiero. Le cose materiali sono

pratiche e funzionali, fatte per essere adoperate. Le altre si

raggiungono con la mente. Nel caso delle arti visive, però, si

passa da uno dei sensi – come ci indica il nome stesso.

La funzione dell’arte è estetica; l’estetica dell’arredamento

è funzionale. Penso che ai tempi del Magnifico le cose non

fossero così nette e che nella sua

visione di letterato, prima ancora

che di Signore di Firenze, l’arte e

l’arredamento, come la letteratura

e la musica, potessero concorrere,

insieme, a creare un clima di piacevole

appagamento per l’Uomo evoluto.

Per chi, cioè, voleva elevarsi da una

condizione di pura materialità e incamminarsi sulla via dello

spirito. La contemplazione estetica da una parte, e la funzione

d’uso quotidiano dall’altra, rispondevano allo stesso bisogno

di armonia e bellezza. Erano parti di un unico disegno, senza

connotazioni nette di valore: senza essere, cioè, incasellate

nella cultura alta e in quella bassa, che a volte viene definita,

appunto, cultura materiale.

Il passaggio dalla sfera dell’arte a quella dell’arredamento

ha una linea di confine marcata, espressa in particolare da

uno dei nostri sensi: il tatto. L’arte non si tocca con mano, si

ammira e basta. Gli oggetti di design si toccano e si usano. Al

primo approccio ci avvaliamo della vista per leggere forma

e colore; ma è subito dopo, toccandolo, che cerchiamo di

capire come quel mobile, divano, lampada, tavolo o letto, è

stato lavorato e quali sensazioni ci trasmette. Ettore Sottsass

raccontava in un’intervista che “toccare una superficie di

laminato è un tale brivido sensoriale che comincia a diventare

interessante”. E si riferiva appunto al laminato, elemento

innaturale ma piatto, senza asperità, senza matericità.

Di fronte alla trama di un tessuto o alla lavorazione di un

mobile i brividi possono solo moltiplicarsi. Oltre al tatto,

infine, ci sono oggetti su cui possiamo sederci o sdraiarci,

registrando le oscillazioni del benessere, prendendoci il

Tessuto collezione Rinascimento.

Le delicate fiammature della texture in ciniglia

creano linee irregolari che muovono leggermente la superficie,

alternandosi con la struttura di ordito,

valorizzando la palette cromatica.

The delicate flames of the chenille texture create

irregular lines that slightly move the surface,

alternating with the warp structure,

enhancing the color palette.

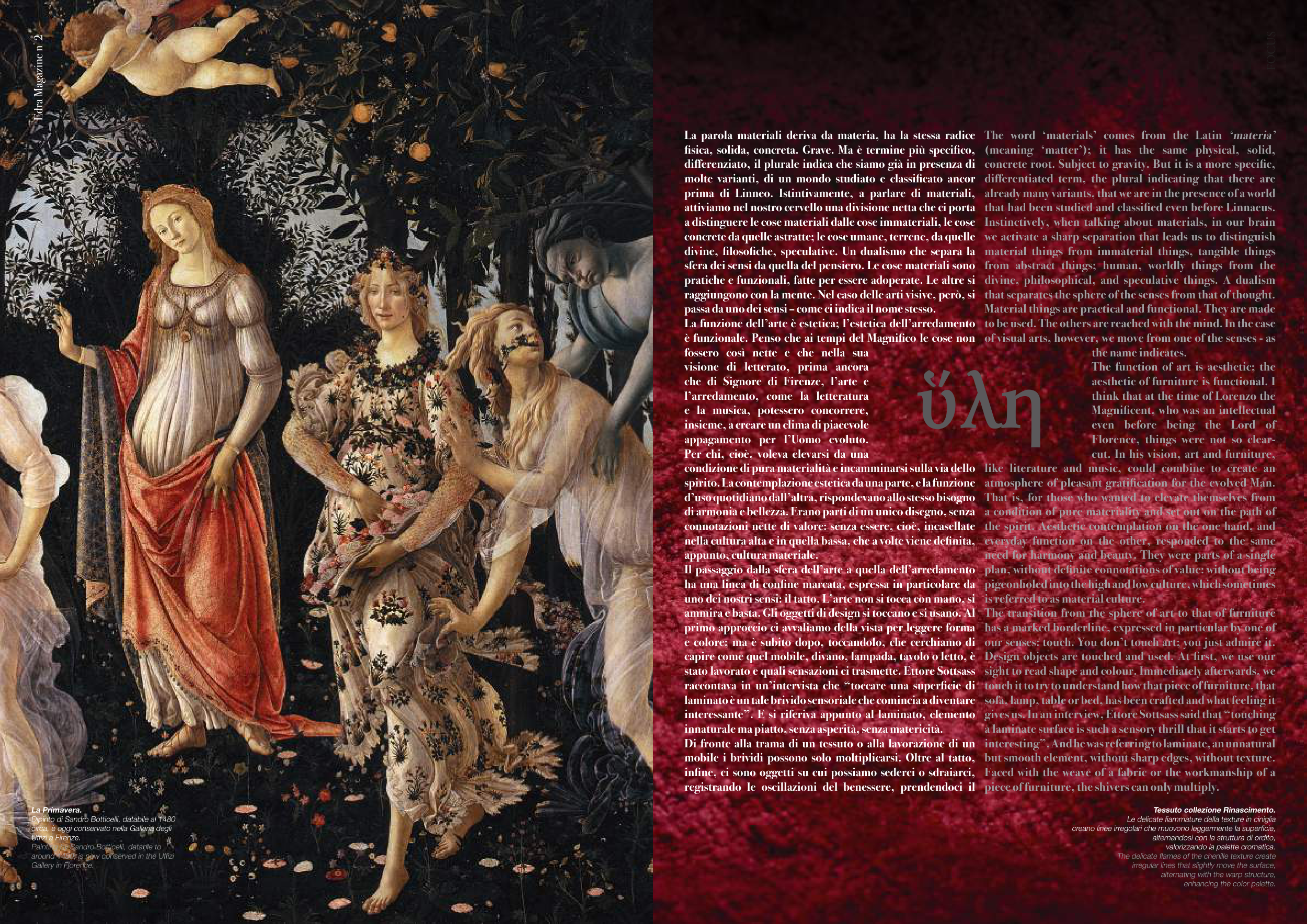

La Primavera.

Dipinto di Sandro Botticelli, databile al 1480

circa, è oggi conservato nella Galleria degli

Uffizi a Firenze.

Painting by Sandro Botticelli, datable to

around 1480, is now conserved in the Uffizi

Gallery in Florence.

ὕλη

The word ‘materials’ comes from the Latin ‘materia’

(meaning ‘matter’); it has the same physical, solid,

concrete root. Subject to gravity. But it is a more specific,

differentiated term, the plural indicating that there are

already many variants, that we are in the presence of a world

that had been studied and classified even before Linnaeus.

Instinctively, when talking about materials, in our brain

we activate a sharp separation that leads us to distinguish

material things from immaterial things, tangible things

from abstract things; human, worldly things from the

divine, philosophical, and speculative things. A dualism

that separates the sphere of the senses from that of thought.

Material things are practical and functional. They are made

to be used. The others are reached with the mind. In the case

of visual arts, however, we move from one of the senses - as

the name indicates.

The function of art is aesthetic; the

aesthetic of furniture is functional. I

think that at the time of Lorenzo the

Magnificent, who was an intellectual

even before being the Lord of

Florence, things were not so clear-

cut. In his vision, art and furniture,

like literature and music, could combine to create an

atmosphere of pleasant gratification for the evolved Man.

That is, for those who wanted to elevate themselves from

a condition of pure materiality and set out on the path of

the spirit. Aesthetic contemplation on the one hand, and

everyday function on the other, responded to the same

need for harmony and beauty. They were parts of a single

plan, without definite connotations of value: without being

pigeonholed into the high and low culture, which sometimes

is referred to as material culture.

The transition from the sphere of art to that of furniture

has a marked borderline, expressed in particular by one of

our senses: touch. You don’t touch art; you just admire it.

Design objects are touched and used. At first, we use our

sight to read shape and colour. Immediately afterwards, we

touch it to try to understand how that piece of furniture, that

sofa, lamp, table or bed, has been crafted and what feeling it

gives us. In an interview, Ettore Sottsass said that “touching

a laminate surface is such a sensory thrill that it starts to get

interesting”. And he was referring to laminate, an unnatural

but smooth element, without sharp edges, without texture.

Faced with the weave of a fabric or the workmanship of a

piece of furniture, the shivers can only multiply.

Edra Magazine n°2

FOCUS