sguardo e una qualità dell’osservazione che ci riporta allo stupore

di una luce che entra improvvisa nella nostra casa o alla forma di

meraviglia elementare che tutti noi abbiamo vissuto abitando sem-

plicemente le nostre case. Ogni immagine di Ghirri è un ritratto

per oggetti e spazi degli autori che li hanno vissuti e che ci hanno

lavorato. Posso quasi vedere Morandi che lavora lento e inesora-

bile, cercando ogni volta, in una leggera variazione sul tema della

Natura Morta, il significato profondo e silenzioso delle nostre esi-

stenze. Poi lo sguardo si volta al

letto bianco, contadino, appena

rifatto, ai comodini vicini, op-

pure alla porta in legno che dà

nell’appartamento. In ogni im-

magine si sente l’amore di chi ha

osservato in silenzio e ha lasciato

che quel vuoto potesse espri-

mersi, offrendoci un frammento

momentaneo dell’anima di quel

luogo.

È la stessa emozione che provano

tutti i protagonisti anonimi del-

le tele del pittore olandese Jan

Vermeer, fissi davanti o a fianco

della grande finestra da cui sono

inondati di luce. Non si vede mai

fuori, ma solo quello sguardo

assorto o stupito di chi sta svol-

gendo un’azione precisa di cui

l’ambiente domestico diventa

eco che riverbera lo stato d’ani-

mo. La luce del nord è padrona,

ma anche la capacità di questi an-

goli, così perfettamente immagi-

nati, di ampliare e accogliere gli

stati d’animo individuali, rende

questi momenti unici, universali.

La bellezza borghese e domesti-

ca dei luoghi rivela l’incanto del

particolare, del dettaglio che narra un mondo intero e della me-

raviglia che lo accompagna, se solo si ha la voglia di rallentare e

osservare. Ogni tappeto, tessuto, brocca, bicchiere, mobilio, map-

pa geografica alla parete, finestra, diventa occasione di meraviglia,

trappola per gli occhi e tutti i sensi. Rivela il potere di ogni singolo

dettaglio di rapirci, rallentando il corso distratto della nostra vita.

Il sentimento di meraviglia non ha una definita scala di riferimento,

non ha nulla a che fare con la grandezza, ma con l’intensità di quel-

lo che riesce a risvegliare in un desiderio latente che ci accompa-

gna e che si materializza nell’incontro di un luogo o di un oggetto

che sembrava attenderci.

La scala minuta del domestico tende alla compressione simbolica e

visiva di ogni elemento. Annulla la miopia che spesso ci accompa-

gna, offrendo occasioni d’incontro inattese che ci avvicinano a una

dimensione quasi sacrale del luogo e dei suoi caratteri profondi,

che siano positivi o negativi.

Il potere di un dettaglio o di un odore che emerge improvviso ha la

capacità di risvegliare emozioni profonde, incagliate nell’animo e

nella memoria, ampliando a dismisura lo spazio e il metro con cui

lo osserviamo. Alcuni spazi domestici, non necessariamente addo-

mesticati nel nostro spirito, offrono, attraverso dettagli apparente-

mente innocui, un potere scatenante delle emozioni private capaci

di raccontare in un attimo gioia, illusioni, violenza, sopraffazione,

speranze, tradimenti, legami, trasformando i luoghi più familiari in

condizioni universali, condivisibili.

La casa come raccolta delle ossessioni borghesi e contemporanee

risuona in maniera paradossale con le Wunderkammer che si mol-

tiplicarono in tutta Europa tra il Cinquecento e il Settecento. Ca-

mere preziose e riservate a pochi intimi in cui il ricco committente

raccoglieva tutto quello che poteva sembrare raro, sorprendente,

inaspettato, mostruoso tra le stranezze della Natura, le opere di

mondi lontani e il virtuosismo tecnico e artigianale dei prodotti.

Ogni oggetto doveva sorprendere, microcosmo soggiogante tutti i

sensi e insieme raccolta di bellezza in uno spazio separato dal resto

del palazzo, scrigno in cui perdersi e viaggio nella memoria e bel-

lezza di un mondo che stava espandendosi agli occhi degli abitanti

del vecchio mondo. Il tempo che corre sempre più veloce prende

la forma dei primi orologi meccanici e degli automi cesellati nei

metalli più preziosi che popolano queste stanze insieme ad animali

a tre teste, antichità, quadri che rimandano ad altri mondi e pae-

saggi esotici, conchiglie e coralli lavorati preziosamente, papiri e

polvere di mummia, gioielli, animali tropicali impagliati, costumi,

piume, reliquie, parti anatomiche riprodotte in cera. Materiali che

invadono gli occhi e i sensi. Labirinto della mente in cui perdersi

in un mondo che non sapeva ancora se essere alchemico o moder-

no, ma che celava nel cuore profondo della residenza nobiliare uno

scrigno protetto gelosamente.

Ogni interno domestico diventa una potenziale scatola del tempo,

come nei lavori dell’artista americano Gordon Matta Clark che, tra

gli anni Sessanta e Settanta del secolo scorso, acquistava case ab-

bandonate nelle periferie delle grandi città statunitensi e le segava

longitudinalmente per portare in scena, all’aperto, tutte le tracce

infinite delle vite che le avevano attraversate. Improvvisamente,

quei pezzi esposti in un museo, ci raccontano della nostra storia

e della sua fragilità aggrappate a una tappezzeria strappata, alla sa-

goma di un quadro che non c’è più, ai segni dei nostri passi sul

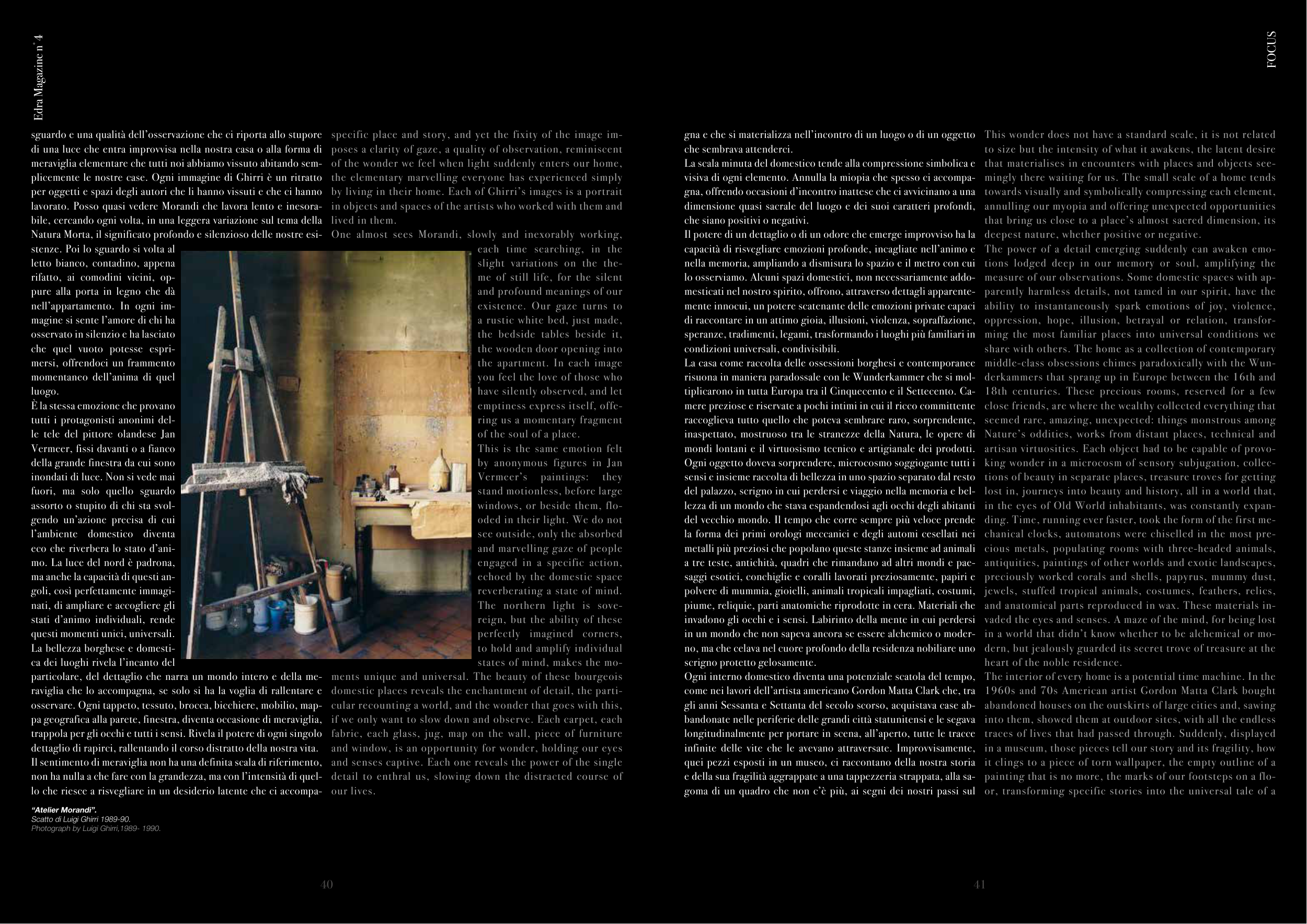

“Atelier Morandi”.

Scatto di Luigi Ghirri 1989-90.

Photograph by Luigi Ghirri,1989- 1990.

specific place and story, and yet the fixity of the image im-

poses a clarity of gaze, a quality of observation, reminiscent

of the wonder we feel when light suddenly enters our home,

the elementary marvelling everyone has experienced simply

by living in their home. Each of Ghirri’s images is a portrait

in objects and spaces of the artists who worked with them and

lived in them.

One almost sees Morandi, slowly and inexorably working,

each time searching, in the

slight variations on the the-

me of still life, for the silent

and profound meanings of our

existence. Our gaze turns to

a rustic white bed, just made,

the bedside tables beside it,

the wooden door opening into

the apartment. In each image

you feel the love of those who

have silently observed, and let

emptiness express itself, offe-

ring us a momentary fragment

of the soul of a place.

This is the same emotion felt

by anonymous figures in Jan

Vermeer’s

paintings:

they

stand motionless, before large

windows, or beside them, flo-

oded in their light. We do not

see outside, only the absorbed

and marvelling gaze of people

engaged in a specific action,

echoed by the domestic space

reverberating a state of mind.

The northern light is sove-

reign, but the ability of these

perfectly imagined corners,

to hold and amplify individual

states of mind, makes the mo-

ments unique and universal. The beauty of these bourgeois

domestic places reveals the enchantment of detail, the parti-

cular recounting a world, and the wonder that goes with this,

if we only want to slow down and observe. Each carpet, each

fabric, each glass, jug, map on the wall, piece of furniture

and window, is an opportunity for wonder, holding our eyes

and senses captive. Each one reveals the power of the single

detail to enthral us, slowing down the distracted course of

our lives.

This wonder does not have a standard scale, it is not related

to size but the intensity of what it awakens, the latent desire

that materialises in encounters with places and objects see-

mingly there waiting for us. The small scale of a home tends

towards visually and symbolically compressing each element,

annulling our myopia and offering unexpected opportunities

that bring us close to a place’s almost sacred dimension, its

deepest nature, whether positive or negative.

The power of a detail emerging suddenly can awaken emo-

tions lodged deep in our memory or soul, amplifying the

measure of our observations. Some domestic spaces with ap-

parently harmless details, not tamed in our spirit, have the

ability to instantaneously spark emotions of joy, violence,

oppression, hope, illusion, betrayal or relation, transfor-

ming the most familiar places into universal conditions we

share with others. The home as a collection of contemporary

middle-class obsessions chimes paradoxically with the Wun-

derkammers that sprang up in Europe between the 16th and

18th centuries. These precious rooms, reserved for a few

close friends, are where the wealthy collected everything that

seemed rare, amazing, unexpected: things monstrous among

Nature’s oddities, works from distant places, technical and

artisan virtuosities. Each object had to be capable of provo-

king wonder in a microcosm of sensory subjugation, collec-

tions of beauty in separate places, treasure troves for getting

lost in, journeys into beauty and history, all in a world that,

in the eyes of Old World inhabitants, was constantly expan-

ding. Time, running ever faster, took the form of the first me-

chanical clocks, automatons were chiselled in the most pre-

cious metals, populating rooms with three-headed animals,

antiquities, paintings of other worlds and exotic landscapes,

preciously worked corals and shells, papyrus, mummy dust,

jewels, stuffed tropical animals, costumes, feathers, relics,

and anatomical parts reproduced in wax. These materials in-

vaded the eyes and senses. A maze of the mind, for being lost

in a world that didn’t know whether to be alchemical or mo-

dern, but jealously guarded its secret trove of treasure at the

heart of the noble residence.

The interior of every home is a potential time machine. In the

1960s and 70s American artist Gordon Matta Clark bought

abandoned houses on the outskirts of large cities and, sawing

into them, showed them at outdoor sites, with all the endless

traces of lives that had passed through. Suddenly, displayed

in a museum, those pieces tell our story and its fragility, how

it clings to a piece of torn wallpaper, the empty outline of a

painting that is no more, the marks of our footsteps on a flo-

or, transforming specific stories into the universal tale of a

Edra Magazine n°4

40

41

FOCUS