28

29

visione di un quadro di Lucian Freud, Big Sue, con una donna

scompostamente sdraiata su un divano Chesterfield di cretonne. “Sfatto –

ricorda Binfaré – nasce in un momento in cui percepivo la fatica del mondo

occidentale, la sua gravità, la decadenza. Il dipinto mi ha trasmesso queste

sensazioni. E io ho cercato di trasferirle in un divano: un tipico divano

borghese, ma disfatto e scomposto”. Che sia proprio il divano il centro

nevralgico dell’abitare contemporaneo? Binfaré ne è convinto. Tanto che

nel film-ritratto che Giovanni Gastel gli ha dedicato sceglie di parlare seduto

su uno dei suoi divani, Pack, quello con la seduta che ha il colore del ghiaccio

del Polo e lo schienale a forma di un orso polare. Mentre ne parla, accarezza

la testa dell’orso. È un gesto spontaneo, non

pensato, probabilmente neanche voluto. Ma

proprio per questo – per dirla con Barthes – è

un gesto che “punge”: perché esprime e

sintetizza tutta la potenziale tenerezza del

creatore nei confronti della sua creatura.

Perché svela il rapporto intimo e complice che

ogni progettista intrattiene con i risultati del

proprio lavoro. Ed è proprio questa intimità

che il film di Giovanni Gastel (che ora si può

vedere in versione integrale su edra.com) riesce

a evidenziare con delicatezza e complicità: non

il gelido ritratto di un artista scrutato con

distacco né una collezione di dichiarazioni

apologetiche fatte da estimatori più o meno

interessati, ma quasi una confessione, una

dichiarazione di poetica, lo svelamento di un

metodo. Mentre le immagini scorrono sul

grande schermo issato sul palco del Teatro

dove di solito risuonano musiche e arie

immortali, in sala prende corpo la sensazione

diffusa e condivisa che anche in quel bianco e

nero c’è qualcosa che sfida il tempo e le mode, e

che si avvicina a uno dei bisogni primari di ogni

essere umano: il desiderio di avere luoghi in cui rifugiarsi, una casa-tana in

cui proteggersi dalle insidie del mondo. Francesco Binfaré da più di mezzo

secolo ha lavorato e creato per offrire risposte a questo desiderio/bisogno.

L’ha fatto in modo sorprendente e visionario. E solo un altro visionario

come Gastel poteva cogliere con questa nitidezza il senso e il valore del suo

lavoro. Anche Valerio e Monica Mazzei, la sera del 9 giugno, erano

emozionati e commossi sul palco della Scala. Consapevoli di aver contribuito

in prima persona a dar forma e voce all’immaginazione di due creatori. E di

avere concorso in questo modo a generare l’incanto.

Silvana Annicchiarico

Architetto, vive a Milano, svolge attività di ricerca, di critica e di didattica. È consulente per enti pubblici e aziende. Attraverso progetti espositivi ed editoriali si occupa di temi

contemporanei, dell’opera di grandi maestri e di nuovi protagonisti del design. Dal 2007 al 2018 è stata ideatrice e Direttore del Triennale Design Museum della Triennale di Milano.

Dal 2019 è Docente di Storia del design all’Università Isia di Pordenone. Dal 2019 al 2022 è stata membro del Comitato Tecnico Scientifico per i Musei e l’economia della cultura

del MIBAC. Collabora con il Ministero degli Affari Esteri per mostre itineranti nel mondo, scrive per “La Repubblica” e “Domus”.

Architect, she lives in Milan and works as a researcher, critic and teacher. She is consultant for public organisations and companies. Through exhibition and editorial projects she

deals with contemporary issues, the works of great masters and new names of design. From 2007 to 2018 she was director of the Triennale Design Museum of the Milan Triennale.

Since 2019 she has been Professor of History of Design at the Isia University of Pordenone. From 2019 to 2022 she was a member of the Technical Scientific Committee for

Museums and the economy of culture of the MIBAC. She cooperates with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs for traveling exhibitions around the world and writes for La Repubblica and

Domus.

by Lucian Freud, Big Sue, where a woman is lying in an unseemly manner

on a Chesterfield sofa made of cretonne: “Sfatto”, recalls Binfaré, “was

born at a time when I perceived the fatigue of the western world, its gravity,

its decadence. The painting conveyed these feelings to me. And I tried to

transfer them to a sofa: a typical bourgeois sofa, but unmade and untidy”.

Is the sofa the hub of contemporary living? Binfaré is convinced of this. So

much so, that in the film portrait that Giovanni Gastel dedicated to him,

he chooses to speak seated on one of his sofas, Pack, the one with the seat

the colour of polar ice and the backrest in the shape of a polar bear. As he

speaks, he strokes the bear’s head. It is a spontaneous gesture, not planned,

probably not even meant. But precisely for

this reason - as Barthes would say - it is a

gesture that ‘stings’: because it expresses and

summarises all the potential tenderness of the

creator towards his creature. Because it reveals

the intimate and conspiratorial relationship

that every designer has with the outcome of

his work. And it is precisely this intimacy that

Giovanni Gastel’s film (which can now be seen

in its integral version on edra.com) successfully

highlights with delicacy and complicity: not

the icy portrait of an artist scrutinised with

detachment, nor a collection of apologetic

declarations made by more or less interested

admirers, but almost a confession, a poetic

statement, the disclosure of a method.

As the images slide on the big screen set on

the theatre stage where immortal music and

arias usually resound, in the auditorium the

audience starts feeling that there is something

- even in that black and white - that defies time

and fashion trends, and that comes close to one

of the primary needs of every human being:

the desire to have a place to take refuge, a den-

house in which to protect oneself from the pitfalls of the world. For more

than half a century Francesco Binfaré has worked and created to offer his

answers to this desire/need. And he did it in a surprising and visionary way.

Only another visionary as Gastel could grasp the meaning and value of his

work with such clarity. On the evening of 9 June, Valerio and Monica Mazzei

were also moved and touched on stage at La Scala. They were aware that

they had personally contributed to giving shape and voice to the imagination

of two creators. And in this way, they have contributed to generating the

enchantment.

accendere un fuoco nella mente dell’imprenditore che poi la dovrà realizzare.

“Quando incontri il committente – dice – non devi avere un progetto, ma

un’idea. Devi saperla comunicare. Devi coinvolgere l’altro. E in questo

processo è molto importante lo scambio di energia”. I suoi divani sono nati

così: dalla capacità di far innamorare un’azienda di una sua visione. Abituato

a svegliarsi presto, alle cinque del mattino, in quel momento sospeso fra il

sonno e la veglia, Binfaré confessa di avere spesso come delle visioni: “Una

volta ho sognato un deserto rosso su cui pioveva nero. Petrolio, forse. Da

questo mare nero spuntava un’isoletta rossa. Sono andato in cucina per

cercare una matita e segnarmi la forma di questa isoletta, ma non ho trovato

matite. Allora ho preso una forbice e ho ritagliato la forma nella carta. Poi ho

fatto dei tagli trasversali e delle pieghe. Flap è nato così: una zattera con delle

parti che si sollevano. Edra aveva già un giunto che funzionava per i

movimenti orizzontali, si trattava solo di crearne un altro per i movimenti

verticali”. La tecnologia al servizio della visione, non viceversa. E la libertà

assoluta nell’immaginare forme nuove e multifunzionali con la complicità di

un’azienda come Edra che crede nella necessità di evitare l’effetto-pialla

della globalizzazione tanto negli oggetti quanto nel pensiero. Ogni progetto

di Binfaré nasce da un’ispirazione particolare. “All’inizio – ha scritto in un

suo testo del 2013 – c’è uno spazio immaginario vuoto nella mia mente,

come una scena teatrale in attesa della storia. A un certo punto comincia a

nascermi una narrazione e man mano il divano prende forma e riempie da

solo la scena e diventa la forma della storia”. Questa idea che il progettare

abbia a che fare con il narrare e che la casa sia assimilabile a un palco vuoto in

cui il mobile può dar corpo a una narrazione possibile è ricorrente in Binfaré

così come in altri grandi innovatori della sua generazione, da Gaetano Pesce

a Alessandro Mendini. Se non è narrativa, la matrice della sua ispirazione

deriva da un’attenta osservazione dei gesti, delle abitudini e dei bisogni. Un

solo esempio: durante un’estate in Puglia Binfaré osserva i bagnanti che

prendono il sole sulle rocce e sugli scogli. In teoria in quella posizione i corpi

dovrebbero essere scomodi, ma in realtà si adattano alla configurazione del

luogo, e trovano una posizione consona. Binfaré ne parla con Valerio Mazzei

che ha appena messo a punto un materiale innovativo, il Gellyfoam®, capace

di accogliere qualsiasi posizione del corpo. Nasce così, con questa “gelatina

di poliuretano”, il divano On the Rocks, dove Binfaré taglia lo schienale dal

sedile, per ottenere una forma totalmente libera, senza vincoli, che consente

pieno movimento sulla superficie. Un divano come Pack nasce invece

dall’osservazione della natura: un orso sdraiato sulla banchisa, che si può

spostare liberamente. “Ho immaginato che se il mondo si potesse definire

come una superficie che si sta rompendo e frazionando in tante piccole

unità, come la banchisa, l’orso poteva rappresentare il simbolo di una grande

dimensione affettiva”. Una genesi culturale ce l’ha invece Sfatto, nato dalla

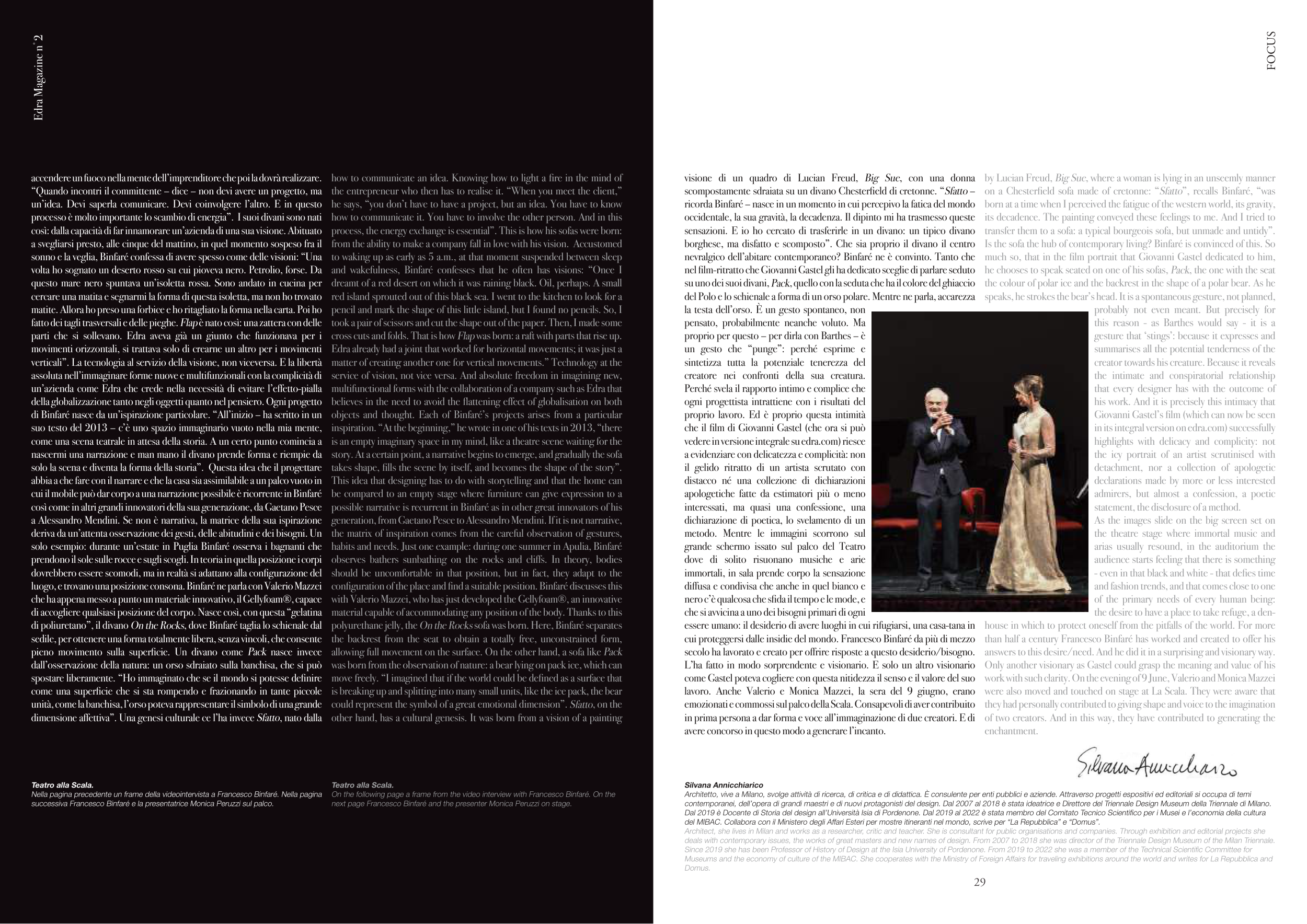

Teatro alla Scala.

Nella pagina precedente un frame della videointervista a Francesco Binfaré. Nella pagina

successiva Francesco Binfaré e la presentatrice Monica Peruzzi sul palco.

Teatro alla Scala.

On the following page a frame from the video interview with Francesco Binfaré. On the

next page Francesco Binfaré and the presenter Monica Peruzzi on stage.

how to communicate an idea. Knowing how to light a fire in the mind of

the entrepreneur who then has to realise it. “When you meet the client,”

he says, “you don’t have to have a project, but an idea. You have to know

how to communicate it. You have to involve the other person. And in this

process, the energy exchange is essential”. This is how his sofas were born:

from the ability to make a company fall in love with his vision. Accustomed

to waking up as early as 5 a.m., at that moment suspended between sleep

and wakefulness, Binfaré confesses that he often has visions: “Once I

dreamt of a red desert on which it was raining black. Oil, perhaps. A small

red island sprouted out of this black sea. I went to the kitchen to look for a

pencil and mark the shape of this little island, but I found no pencils. So, I

took a pair of scissors and cut the shape out of the paper. Then, I made some

cross cuts and folds. That is how Flap was born: a raft with parts that rise up.

Edra already had a joint that worked for horizontal movements; it was just a

matter of creating another one for vertical movements.” Technology at the

service of vision, not vice versa. And absolute freedom in imagining new,

multifunctional forms with the collaboration of a company such as Edra that

believes in the need to avoid the flattening effect of globalisation on both

objects and thought. Each of Binfaré’s projects arises from a particular

inspiration. “At the beginning,” he wrote in one of his texts in 2013, “there

is an empty imaginary space in my mind, like a theatre scene waiting for the

story. At a certain point, a narrative begins to emerge, and gradually the sofa

takes shape, fills the scene by itself, and becomes the shape of the story”.

This idea that designing has to do with storytelling and that the home can

be compared to an empty stage where furniture can give expression to a

possible narrative is recurrent in Binfaré as in other great innovators of his

generation, from Gaetano Pesce to Alessandro Mendini. If it is not narrative,

the matrix of inspiration comes from the careful observation of gestures,

habits and needs. Just one example: during one summer in Apulia, Binfaré

observes bathers sunbathing on the rocks and cliffs. In theory, bodies

should be uncomfortable in that position, but in fact, they adapt to the

configuration of the place and find a suitable position. Binfaré discusses this

with Valerio Mazzei, who has just developed the Gellyfoam®, an innovative

material capable of accommodating any position of the body. Thanks to this

polyurethane jelly, the On the Rocks sofa was born. Here, Binfaré separates

the backrest from the seat to obtain a totally free, unconstrained form,

allowing full movement on the surface. On the other hand, a sofa like Pack

was born from the observation of nature: a bear lying on pack ice, which can

move freely. “I imagined that if the world could be defined as a surface that

is breaking up and splitting into many small units, like the ice pack, the bear

could represent the symbol of a great emotional dimension”. Sfatto, on the

other hand, has a cultural genesis. It was born from a vision of a painting

Edra Magazine n°2

FOCUS