Vico resembled a puff of wind. A light sketch, not creased at

all. You knew immediately that he liked simplicity and that he

listened to music when he worked. After all, Schopenhauer

and Goethe spoke of architecture as frozen music. Vico was

a note that didn’t make too much noise, yet filled the air. He

was Milanese, very much so. He loved recognising his family

history in the city, he enjoyed discovering that the house

he lived in, and that he’d renovated, was built by his great-

grandfather at the time of Napoleon. He used to say that

simplicity is the most complicated thing in the world. And

even more sophisticated. If people asked him what object he

wished he’d designed, he’d reply: the umbrella. Because it’s

needed, it’s useful, it’s extraordinary and timeless. Flashes

of beauty, for him. He meant that it only takes a moment to

marvel and discover different methods (and worlds).

He wasn’t too precious about dealing with business, on the

contrary, he believed in trade, in serial production. Vico and

Maddalena (De Padova) understood one another, there was

no need for drawings, a sketch on the back of an envelope

sufficed. This was an exchange between two quick minds,

which often took place in the house in Via Marina, where

Maddalena brought the prototypes. She was more stubborn,

he was more conciliatory, and a guest could not remain

neutral. Vico admired Maddalena’s power of observation

and critical thinking: “She immediately spots a design’s

weakness.” He was always ready to rebuild, to start over, to

find alternative solutions.

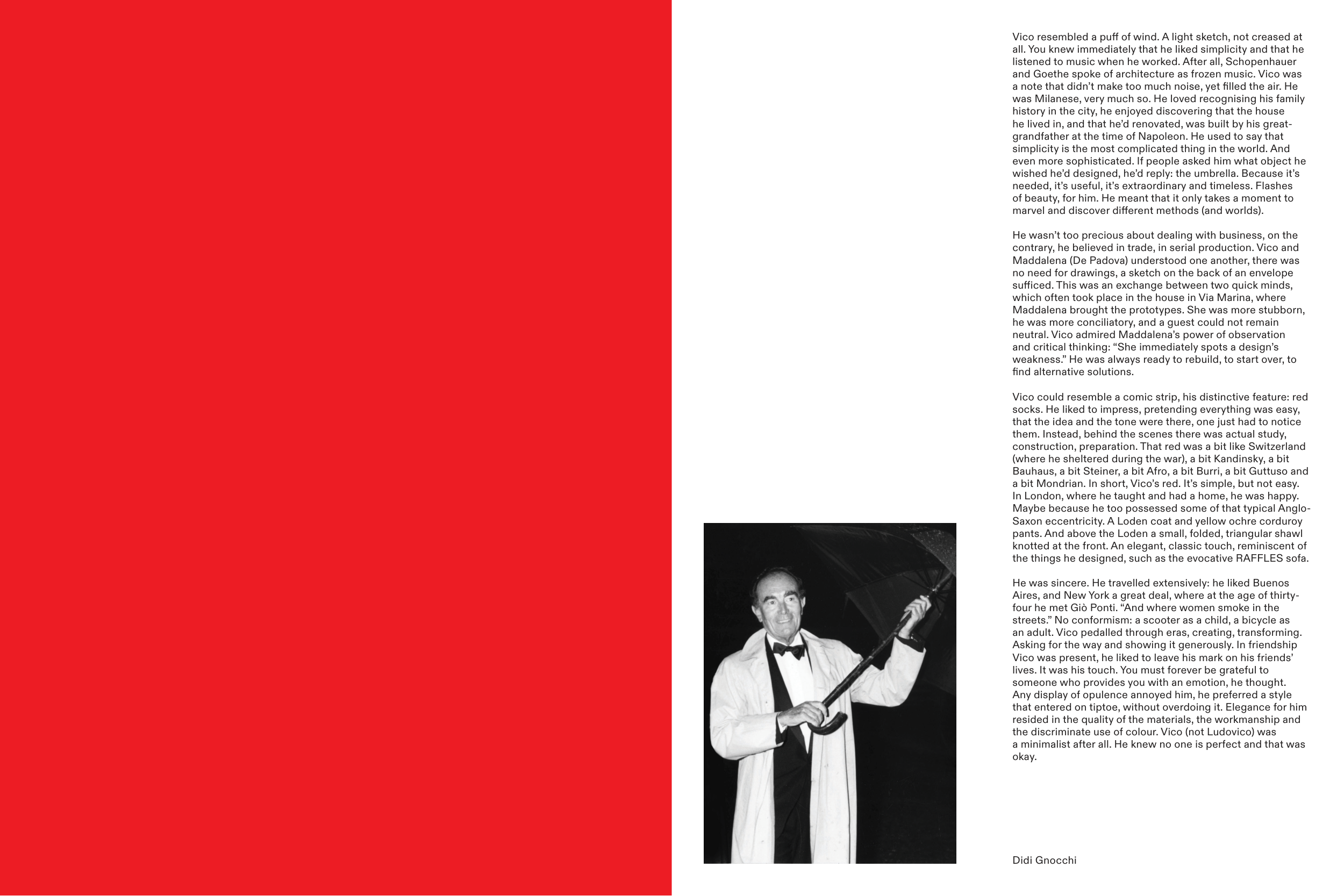

Vico could resemble a comic strip, his distinctive feature: red

socks. He liked to impress, pretending everything was easy,

that the idea and the tone were there, one just had to notice

them. Instead, behind the scenes there was actual study,

construction, preparation. That red was a bit like Switzerland

(where he sheltered during the war), a bit Kandinsky, a bit

Bauhaus, a bit Steiner, a bit Afro, a bit Burri, a bit Guttuso and

a bit Mondrian. In short, Vico’s red. It’s simple, but not easy.

In London, where he taught and had a home, he was happy.

Maybe because he too possessed some of that typical Anglo-

Saxon eccentricity. A Loden coat and yellow ochre corduroy

pants. And above the Loden a small, folded, triangular shawl

knotted at the front. An elegant, classic touch, reminiscent of

the things he designed, such as the evocative RAFFLES sofa.

He was sincere. He travelled extensively: he liked Buenos

Aires, and New York a great deal, where at the age of thirty-

four he met Giò Ponti. “And where women smoke in the

streets.” No conformism: a scooter as a child, a bicycle as

an adult. Vico pedalled through eras, creating, transforming.

Asking for the way and showing it generously. In friendship

Vico was present, he liked to leave his mark on his friends’

lives. It was his touch. You must forever be grateful to

someone who provides you with an emotion, he thought.

Any display of opulence annoyed him, he preferred a style

that entered on tiptoe, without overdoing it. Elegance for him

resided in the quality of the materials, the workmanship and

the discriminate use of colour. Vico (not Ludovico) was

a minimalist after all. He knew no one is perfect and that was

okay.

Didi Gnocchi