C 09 33

Developed by the not-for-profit Ikea Foundation with UNHCR

over the past five years, the Better Shelter consists of a sturdy steel

frame clad with insulated polypropylene panels, along with a solar

panel on the roof that provides four hours of electric light, or mobile

phone charging via a USB port. Crucially, it is firmly anchored to

the ground and the walls are stab-proof, a potentially life-saving

feature given that such shelters are often sited where violence is rife

and gender-based.

Despite the dramatic increase in the number of people being dis-

placed around the world, with UNHCR estimating there are now 2.6

million refugees who have lived in camps for over five years, and some

for more than a generation, the typical flimsy tent hasn’t changed

much. Cold in winter and sweltering in summer, tents still rely on

canvas, ropes and poles. They generally last about six months, leaking

when it rains and blowing away in strong winds.

A Kit Against Precariety

At a price of US$1,250, a Better Shelter costs twice as much as a typi-

cal emergency tent, but it provides security, insulation and durability,

and it lasts for at least three years. Beyond that time, when the plastic

panels might degrade, the frame can be reused and clad in whatever

local materials are to hand, from mud bricks to corrugated iron.

Since production started in June 2015, over 16,000 have been de-

ployed to crisis locations like Nepal, where Médecins Sans Frontières

used them as clinics after the earthquake. Several thousand have been

sent to Iraq, and hundreds to Djibouti to house refugees fleeing Yemen.

“It’s almost like playing with Lego,” says Per Heggenes, CEO of

the Ikea Foundation. “You can put it together in different ways to

make small clinics or temporary schools. A family could also take it

apart and take it with them, using the shelter as a framework around

which to build with local materials.”

The design, which has been showered with international accolades,

is already housed in the permanent collection of the Museum of

Modern Art in New York, but the project hasn’t always had an easy

ride. It made headlines in 2015 when Zurich ordered 62 to house

asylum-seekers, but found it couldn’t use them because they were fire

hazards. “The shelters were never designed to meet Swiss fire regu-

lations,” says Märta Terne of Better Shelter, “or to be used indoors

as the city proposed. The humanitarian aid world doesn’t adhere to

the same safety standards as you would for permanent buildings in

Europe made of concrete and stone. But there are strict rules about

the distance between shelters and no cooking is allowed inside.”

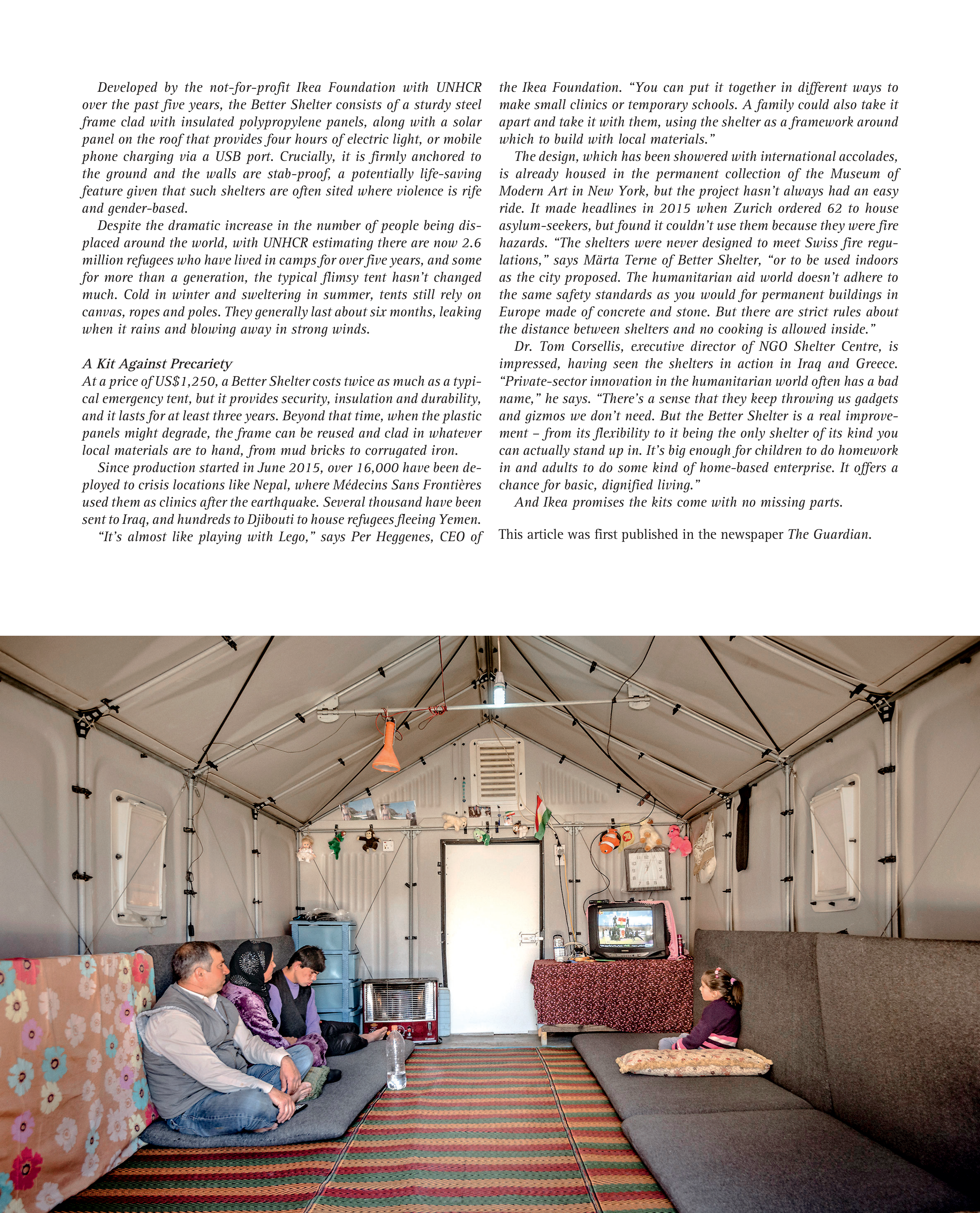

Dr. Tom Corsellis, executive director of NGO Shelter Centre, is

impressed, having seen the shelters in action in Iraq and Greece.

“Private-sector innovation in the humanitarian world often has a bad

name,” he says. “There’s a sense that they keep throwing us gadgets

and gizmos we don’t need. But the Better Shelter is a real improve-

ment – from its flexibility to it being the only shelter of its kind you

can actually stand up in. It’s big enough for children to do homework

in and adults to do some kind of home-based enterprise. It offers a

chance for basic, dignified living.”

And Ikea promises the kits come with no missing parts.

This article was first published in the newspaper The Guardian.