107

106

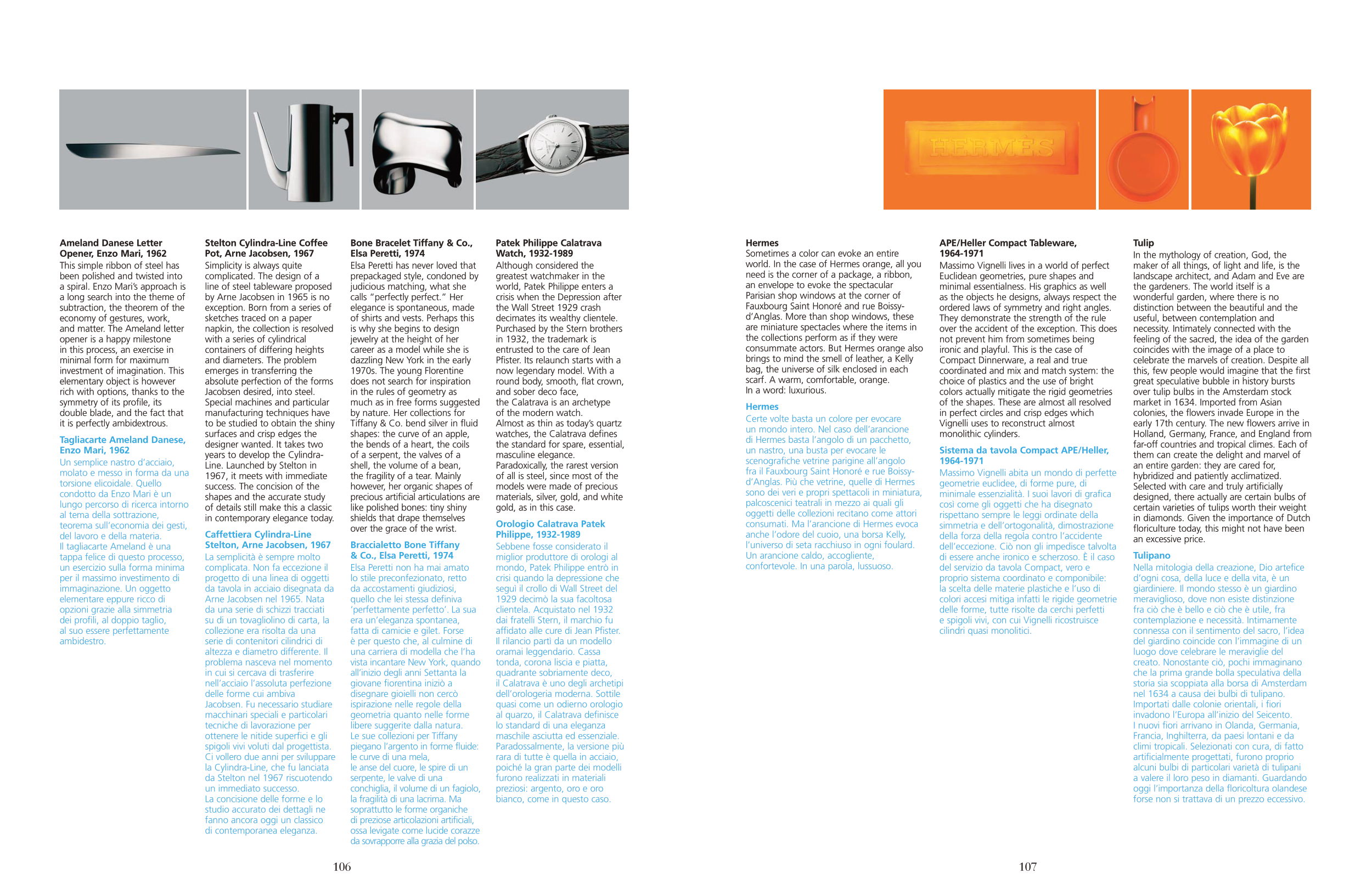

Ameland Danese Letter

Opener, Enzo Mari, 1962

This simple ribbon of steel has

been polished and twisted into

a spiral. Enzo Mari’s approach is

a long search into the theme of

subtraction, the theorem of the

economy of gestures, work,

and matter. The Ameland letter

opener is a happy milestone

in this process, an exercise in

minimal form for maximum

investment of imagination. This

elementary object is however

rich with options, thanks to the

symmetry of its profile, its

double blade, and the fact that

it is perfectly ambidextrous.

Tagliacarte Ameland Danese,

Enzo Mari, 1962

Un semplice nastro d’acciaio,

molato e messo in forma da una

torsione elicoidale. Quello

condotto da Enzo Mari è un

lungo percorso di ricerca intorno

al tema della sottrazione,

teorema sull’economia dei gesti,

del lavoro e della materia.

Il tagliacarte Ameland è una

tappa felice di questo processo,

un esercizio sulla forma minima

per il massimo investimento di

immaginazione. Un oggetto

elementare eppure ricco di

opzioni grazie alla simmetria

dei profili, al doppio taglio,

al suo essere perfettamente

ambidestro.

Stelton Cylindra-Line Coffee

Pot, Arne Jacobsen, 1967

Simplicity is always quite

complicated. The design of a

line of steel tableware proposed

by Arne Jacobsen in 1965 is no

exception. Born from a series of

sketches traced on a paper

napkin, the collection is resolved

with a series of cylindrical

containers of differing heights

and diameters. The problem

emerges in transferring the

absolute perfection of the forms

Jacobsen desired, into steel.

Special machines and particular

manufacturing techniques have

to be studied to obtain the shiny

surfaces and crisp edges the

designer wanted. It takes two

years to develop the Cylindra-

Line. Launched by Stelton in

1967, it meets with immediate

success. The concision of the

shapes and the accurate study

of details still make this a classic

in contemporary elegance today.

Caffettiera Cylindra-Line

Stelton, Arne Jacobsen, 1967

La semplicità è sempre molto

complicata. Non fa eccezione il

progetto di una linea di oggetti

da tavola in acciaio disegnata da

Arne Jacobsen nel 1965. Nata

da una serie di schizzi tracciati

su di un tovagliolino di carta, la

collezione era risolta da una

serie di contenitori cilindrici di

altezza e diametro differente. Il

problema nasceva nel momento

in cui si cercava di trasferire

nell’acciaio l’assoluta perfezione

delle forme cui ambiva

Jacobsen. Fu necessario studiare

macchinari speciali e particolari

tecniche di lavorazione per

ottenere le nitide superfici e gli

spigoli vivi voluti dal progettista.

Ci vollero due anni per sviluppare

la Cylindra-Line, che fu lanciata

da Stelton nel 1967 riscuotendo

un immediato successo.

La concisione delle forme e lo

studio accurato dei dettagli ne

fanno ancora oggi un classico

di contemporanea eleganza.

Bone Bracelet Tiffany & Co.,

Elsa Peretti, 1974

Elsa Peretti has never loved that

prepackaged style, condoned by

judicious matching, what she

calls “perfectly perfect.” Her

elegance is spontaneous, made

of shirts and vests. Perhaps this

is why she begins to design

jewelry at the height of her

career as a model while she is

dazzling New York in the early

1970s. The young Florentine

does not search for inspiration

in the rules of geometry as

much as in free forms suggested

by nature. Her collections for

Tiffany & Co. bend silver in fluid

shapes: the curve of an apple,

the bends of a heart, the coils

of a serpent, the valves of a

shell, the volume of a bean,

the fragility of a tear. Mainly

however, her organic shapes of

precious artificial articulations are

like polished bones: tiny shiny

shields that drape themselves

over the grace of the wrist.

Braccialetto Bone Tiffany

& Co., Elsa Peretti, 1974

Elsa Peretti non ha mai amato

lo stile preconfezionato, retto

da accostamenti giudiziosi,

quello che lei stessa definiva

‘perfettamente perfetto’. La sua

era un’eleganza spontanea,

fatta di camicie e gilet. Forse

è per questo che, al culmine di

una carriera di modella che l’ha

vista incantare New York, quando

all’inizio degli anni Settanta la

giovane fiorentina iniziò a

disegnare gioielli non cercò

ispirazione nelle regole della

geometria quanto nelle forme

libere suggerite dalla natura.

Le sue collezioni per Tiffany

piegano l’argento in forme fluide:

le curve di una mela,

le anse del cuore, le spire di un

serpente, le valve di una

conchiglia, il volume di un fagiolo,

la fragilità di una lacrima. Ma

soprattutto le forme organiche

di preziose articolazioni artificiali,

ossa levigate come lucide corazze

da sovrapporre alla grazia del polso.

Patek Philippe Calatrava

Watch, 1932-1989

Although considered the

greatest watchmaker in the

world, Patek Philippe enters a

crisis when the Depression after

the Wall Street 1929 crash

decimates its wealthy clientele.

Purchased by the Stern brothers

in 1932, the trademark is

entrusted to the care of Jean

Pfister. Its relaunch starts with a

now legendary model. With a

round body, smooth, flat crown,

and sober deco face,

the Calatrava is an archetype

of the modern watch.

Almost as thin as today’s quartz

watches, the Calatrava defines

the standard for spare, essential,

masculine elegance.

Paradoxically, the rarest version

of all is steel, since most of the

models were made of precious

materials, silver, gold, and white

gold, as in this case.

Orologio Calatrava Patek

Philippe, 1932-1989

Sebbene fosse considerato il

miglior produttore di orologi al

mondo, Patek Philippe entrò in

crisi quando la depressione che

seguì il crollo di Wall Street del

1929 decimò la sua facoltosa

clientela. Acquistato nel 1932

dai fratelli Stern, il marchio fu

affidato alle cure di Jean Pfister.

Il rilancio partì da un modello

oramai leggendario. Cassa

tonda, corona liscia e piatta,

quadrante sobriamente deco,

il Calatrava è uno degli archetipi

dell’orologeria moderna. Sottile

quasi come un odierno orologio

al quarzo, il Calatrava definisce

lo standard di una eleganza

maschile asciutta ed essenziale.

Paradossalmente, la versione più

rara di tutte è quella in acciaio,

poiché la gran parte dei modelli

furono realizzati in materiali

preziosi: argento, oro e oro

bianco, come in questo caso.

Hermes

Sometimes a color can evoke an entire

world. In the case of Hermes orange, all you

need is the corner of a package, a ribbon,

an envelope to evoke the spectacular

Parisian shop windows at the corner of

Fauxbourg Saint Honoré and rue Boissy-

d’Anglas. More than shop windows, these

are miniature spectacles where the items in

the collections perform as if they were

consummate actors. But Hermes orange also

brings to mind the smell of leather, a Kelly

bag, the universe of silk enclosed in each

scarf. A warm, comfortable, orange.

In a word: luxurious.

Hermes

Certe volte basta un colore per evocare

un mondo intero. Nel caso dell’arancione

di Hermes basta l’angolo di un pacchetto,

un nastro, una busta per evocare le

scenografiche vetrine parigine all’angolo

fra il Fauxbourg Saint Honoré e rue Boissy-

d’Anglas. Più che vetrine, quelle di Hermes

sono dei veri e propri spettacoli in miniatura,

palcoscenici teatrali in mezzo ai quali gli

oggetti delle collezioni recitano come attori

consumati. Ma l’arancione di Hermes evoca

anche l’odore del cuoio, una borsa Kelly,

l’universo di seta racchiuso in ogni foulard.

Un arancione caldo, accogliente,

confortevole. In una parola, lussuoso.

APE/Heller Compact Tableware,

1964-1971

Massimo Vignelli lives in a world of perfect

Euclidean geometries, pure shapes and

minimal essentialness. His graphics as well

as the objects he designs, always respect the

ordered laws of symmetry and right angles.

They demonstrate the strength of the rule

over the accident of the exception. This does

not prevent him from sometimes being

ironic and playful. This is the case of

Compact Dinnerware, a real and true

coordinated and mix and match system: the

choice of plastics and the use of bright

colors actually mitigate the rigid geometries

of the shapes. These are almost all resolved

in perfect circles and crisp edges which

Vignelli uses to reconstruct almost

monolithic cylinders.

Sistema da tavola Compact APE/Heller,

1964-1971

Massimo Vignelli abita un mondo di perfette

geometrie euclidee, di forme pure, di

minimale essenzialità. I suoi lavori di grafica

così come gli oggetti che ha disegnato

rispettano sempre le leggi ordinate della

simmetria e dell’ortogonalità, dimostrazione

della forza della regola contro l’accidente

dell’eccezione. Ciò non gli impedisce talvolta

di essere anche ironico e scherzoso. È il caso

del servizio da tavola Compact, vero e

proprio sistema coordinato e componibile:

la scelta delle materie plastiche e l’uso di

colori accesi mitiga infatti le rigide geometrie

delle forme, tutte risolte da cerchi perfetti

e spigoli vivi, con cui Vignelli ricostruisce

cilindri quasi monolitici.

Tulip

In the mythology of creation, God, the

maker of all things, of light and life, is the

landscape architect, and Adam and Eve are

the gardeners. The world itself is a

wonderful garden, where there is no

distinction between the beautiful and the

useful, between contemplation and

necessity. Intimately connected with the

feeling of the sacred, the idea of the garden

coincides with the image of a place to

celebrate the marvels of creation. Despite all

this, few people would imagine that the first

great speculative bubble in history bursts

over tulip bulbs in the Amsterdam stock

market in 1634. Imported from Asian

colonies, the flowers invade Europe in the

early 17th century. The new flowers arrive in

Holland, Germany, France, and England from

far-off countries and tropical climes. Each of

them can create the delight and marvel of

an entire garden: they are cared for,

hybridized and patiently acclimatized.

Selected with care and truly artificially

designed, there actually are certain bulbs of

certain varieties of tulips worth their weight

in diamonds. Given the importance of Dutch

floriculture today, this might not have been

an excessive price.

Tulipano

Nella mitologia della creazione, Dio artefice

d’ogni cosa, della luce e della vita, è un

giardiniere. Il mondo stesso è un giardino

meraviglioso, dove non esiste distinzione

fra ciò che è bello e ciò che è utile, fra

contemplazione e necessità. Intimamente

connessa con il sentimento del sacro, l’idea

del giardino coincide con l’immagine di un

luogo dove celebrare le meraviglie del

creato. Nonostante ciò, pochi immaginano

che la prima grande bolla speculativa della

storia sia scoppiata alla borsa di Amsterdam

nel 1634 a causa dei bulbi di tulipano.

Importati dalle colonie orientali, i fiori

invadono l’Europa all’inizio del Seicento.

I nuovi fiori arrivano in Olanda, Germania,

Francia, Inghilterra, da paesi lontani e da

climi tropicali. Selezionati con cura, di fatto

artificialmente progettati, furono proprio

alcuni bulbi di particolari varietà di tulipani

a valere il loro peso in diamanti. Guardando

oggi l’importanza della floricoltura olandese

forse non si trattava di un prezzo eccessivo.