4

The expectation that awaited

the “1919 Bauhaus 1928” MoMA

exhibition in 1938, was not

disappointed. The exhibition,

comprehensively staged by Walter

and Ilse Gropius, introduced the

Bauhaus approach to design

for the first time. In the catalogue

that documents the exhibition,

the programmatics, workshops and

institution protagonists are

portrayed in an encyclopaedic

scope. The momentum was

favourable. No nation in the world

was more in tune with Modernism

than the USA, which was more

optimally prepared for it than any

other. The Americans had been

very enthusiastic about Philip

Johnson’s minimalistically designed

exhibit “Machine Art”, which

celebrated safes, industrial glass

and ship propellers. And now the

Bauhaus with its programmatics

that reconcile industry and craft-

manship.

The designs put on display back

then met with an excellent response

from the open-minded Americans;

especially the objects that emerged

from the metal workshops

drew attention, in particular those

designed by Marianne Brandt.

The fact that Walter Gropius

directed such a clear focus onto

Marianne Brandt’s designs during

the exhibition was in part due

to the extraordinary aesthetic

quality of these objects. These

works distinguished themselves

fundamentally from most of the

other designs both in shape and

proportion as well as in their

aesthetic appearance. In addition,

Gropius used the attention that was

generated to refer to Brandt and

other Bauhaus designers, who

in the meantime were scattered

around the whole world.

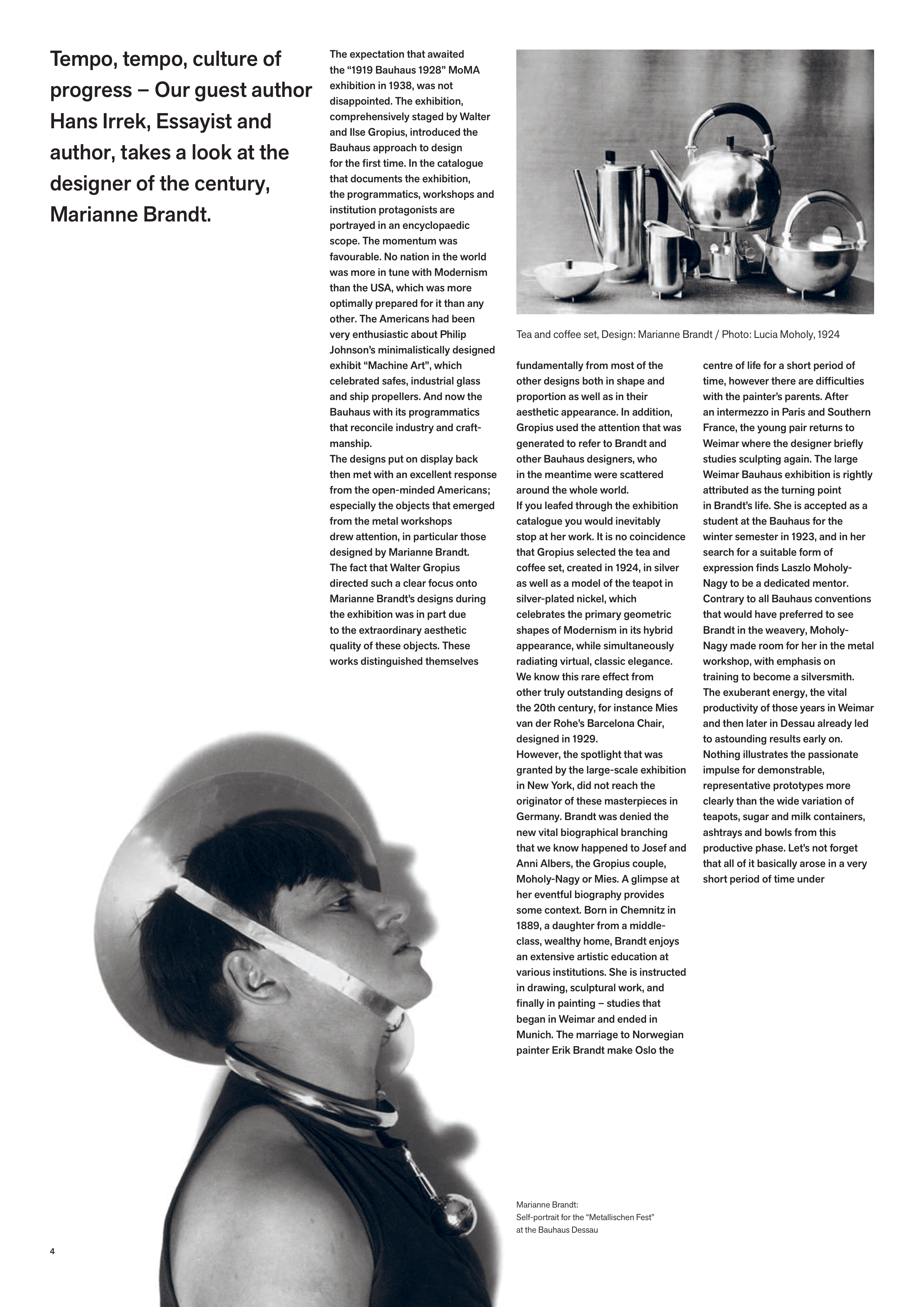

If you leafed through the exhibition

catalogue you would inevitably

stop at her work. It is no coincidence

that Gropius selected the tea and

coffee set, created in 1924, in silver

as well as a model of the teapot in

silver-plated nickel, which

celebrates the primary geometric

shapes of Modernism in its hybrid

appearance, while simultaneously

radiating virtual, classic elegance.

We know this rare effect from

other truly outstanding designs of

the 20th century, for instance Mies

van der Rohe’s Barcelona Chair,

designed in 1929.

However, the spotlight that was

granted by the large-scale exhibition

in New York, did not reach the

originator of these masterpieces in

Germany. Brandt was denied the

new vital biographical branching

that we know happened to Josef and

Anni Albers, the Gropius couple,

Moholy-Nagy or Mies. A glimpse at

her eventful biography provides

some context. Born in Chemnitz in

1889, a daughter from a middle-

class, wealthy home, Brandt enjoys

an extensive artistic education at

various institutions. She is instructed

in drawing, sculptural work, and

finally in painting – studies that

began in Weimar and ended in

Munich. The marriage to Norwegian

painter Erik Brandt make Oslo the

centre of life for a short period of

time, however there are difficulties

with the painter’s parents. After

an intermezzo in Paris and Southern

France, the young pair returns to

Weimar where the designer briefly

studies sculpting again. The large

Weimar Bauhaus exhibition is rightly

attributed as the turning point

in Brandt’s life. She is accepted as a

student at the Bauhaus for the

winter semester in 1923, and in her

search for a suitable form of

expression finds Laszlo Moholy-

Nagy to be a dedicated mentor.

Contrary to all Bauhaus conventions

that would have preferred to see

Brandt in the weavery, Moholy-

Nagy made room for her in the metal

workshop, with emphasis on

training to become a silversmith.

The exuberant energy, the vital

productivity of those years in Weimar

and then later in Dessau already led

to astounding results early on.

Nothing illustrates the passionate

impulse for demonstrable,

representative prototypes more

clearly than the wide variation of

teapots, sugar and milk containers,

ashtrays and bowls from this

productive phase. Let’s not forget

that all of it basically arose in a very

short period of time under

Tea and coffee set, Design: Marianne Brandt / Photo: Lucia Moholy, 1924

Marianne Brandt:

Self-portrait for the “Metallischen Fest”

at the Bauhaus Dessau

Tempo, tempo, culture of

progress – Our guest author

Hans Irrek, Essayist and

author, takes a look at the

designer of the century,

Marianne Brandt.