017

5 There is ample literature concerning the

production of Murano glass; less so regarding

the issues of the design project or dedicated

to lighting. For a basic bibliography on these

issues and more in general an overview of

Italian light design, see A.Bassi, La luce

italiana. Il design delle lampade 1945-2000,

Electa, Milan 2003, pp. 186-203

6. This is one of the cruxes of the theory and

practice of industrial design discussed by

many scholars; it remains a controversial

critical issue, in the face of the “liquidity”,

to use the suggestive definition supplied by

Zygmunt Bauman (Z.Bauman, Modernità

liquida, Laterza, Roma-Bari 2002) of the

ideological, technological and design situation

of contemporary modernism

7. Brief observations on this issue in A.Bassi,

Non tutto il “disegnato” è design, in “Il Sole

24 ore”, September 30 2001 and idem.

Arti applicate e design: dialogo e distinguo,

in Nuovo Antico dalla materia all’artefatto,

edited by F.C. Drago, Rome 2002, pp.37-38

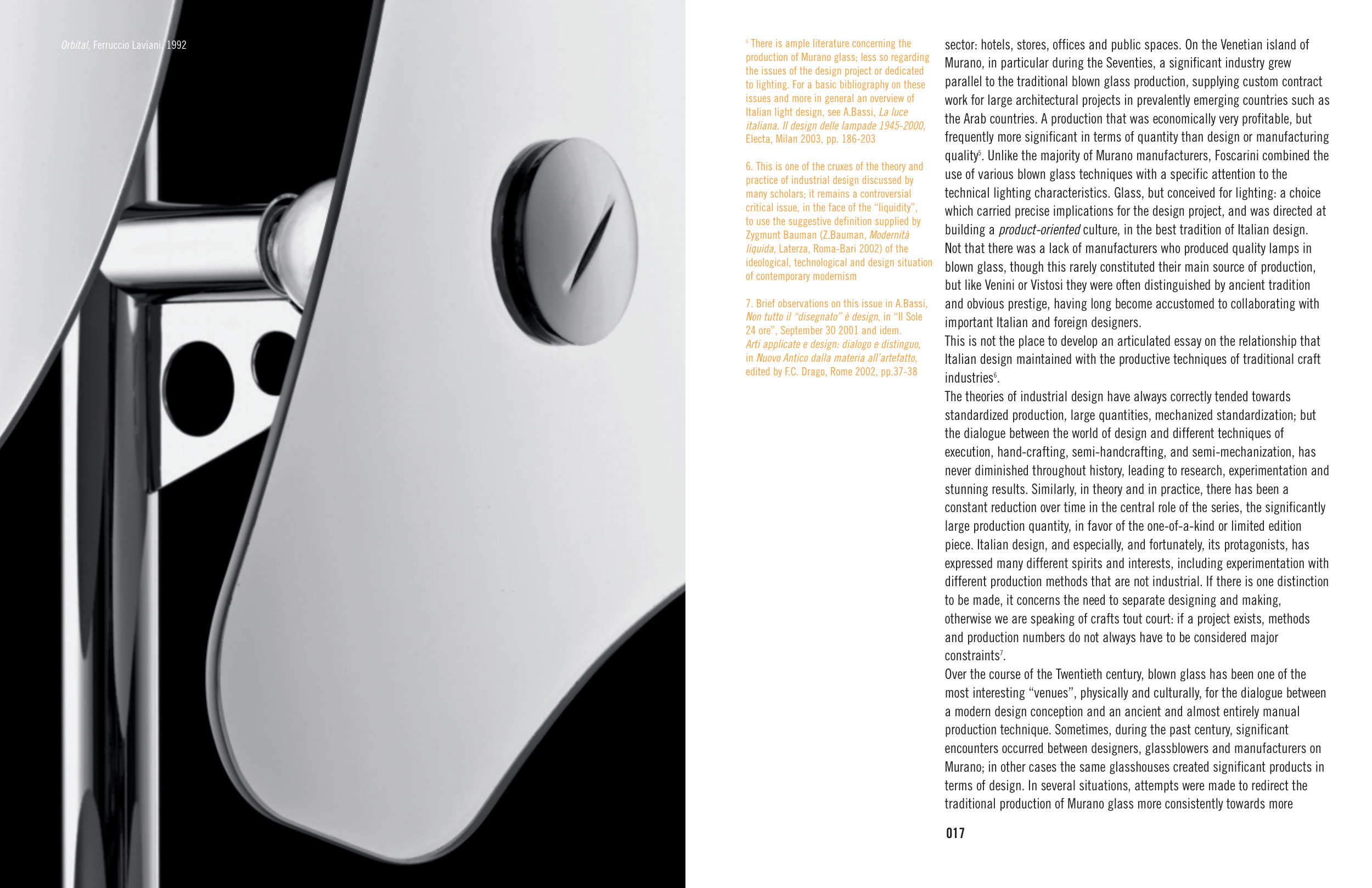

Orbital, Ferruccio Laviani, 1992

sector: hotels, stores, offices and public spaces. On the Venetian island of

Murano, in particular during the Seventies, a significant industry grew

parallel to the traditional blown glass production, supplying custom contract

work for large architectural projects in prevalently emerging countries such as

the Arab countries. A production that was economically very profitable, but

frequently more significant in terms of quantity than design or manufacturing

quality5. Unlike the majority of Murano manufacturers, Foscarini combined the

use of various blown glass techniques with a specific attention to the

technical lighting characteristics. Glass, but conceived for lighting: a choice

which carried precise implications for the design project, and was directed at

building a product-oriented culture, in the best tradition of Italian design.

Not that there was a lack of manufacturers who produced quality lamps in

blown glass, though this rarely constituted their main source of production,

but like Venini or Vistosi they were often distinguished by ancient tradition

and obvious prestige, having long become accustomed to collaborating with

important Italian and foreign designers.

This is not the place to develop an articulated essay on the relationship that

Italian design maintained with the productive techniques of traditional craft

industries6.

The theories of industrial design have always correctly tended towards

standardized production, large quantities, mechanized standardization; but

the dialogue between the world of design and different techniques of

execution, hand-crafting, semi-handcrafting, and semi-mechanization, has

never diminished throughout history, leading to research, experimentation and

stunning results. Similarly, in theory and in practice, there has been a

constant reduction over time in the central role of the series, the significantly

large production quantity, in favor of the one-of-a-kind or limited edition

piece. Italian design, and especially, and fortunately, its protagonists, has

expressed many different spirits and interests, including experimentation with

different production methods that are not industrial. If there is one distinction

to be made, it concerns the need to separate designing and making,

otherwise we are speaking of crafts tout court: if a project exists, methods

and production numbers do not always have to be considered major

constraints7.

Over the course of the Twentieth century, blown glass has been one of the

most interesting “venues”, physically and culturally, for the dialogue between

a modern design conception and an ancient and almost entirely manual

production technique. Sometimes, during the past century, significant

encounters occurred between designers, glassblowers and manufacturers on

Murano; in other cases the same glasshouses created significant products in

terms of design. In several situations, attempts were made to redirect the

traditional production of Murano glass more consistently towards more