In 1442, Angelo Barovier, the artist whose

name would forever remain synonymous

with Murano glass, obtained a permit to

open his own furnace. He would invent a

new type of glass called cristallo, which

looked extremely pure and transparent by

the standards of the time. The invention

was an instant success, occurring just as

the techniques of decoration with enamels

and gold on glass were being perfected.

The end of the century witnessed the in-

troduction of rosechiero, a beautiful bright

red glass, and of rosette, small cylinders

formed out of glass rods, with decorative

motifs appearing in section. These pieces,

inserted into plates of blown glass, were

the precursors of the later “murrine” tech-

nique, a typical XIXth century decoration.

The products of these innovations attract-

ed the attention of the princes and the

European courts: the Medici and the

Sforza families were the first to try and

draw the masters from Murano to their

courts, to give artistic prestige to their own

residences.

The golden century:

protectionism

and imitation

The art of Murano glass reached full ma-

turity during the XVIth century, when “go-

ing to watch glass-making on Murano” be-

came a must for any important person

who came to visit Venice.

With the final re-definition of the

Mariegola, the glassmasters on Murano

became more and more powerful and the

Government of the Most Serene Republic

of Venice, which was beginning to witness

the decline of its own power in those

years, was forced to intensify its protec-

tionist policies to prevent the secrets of

glass technique from leaving the territory

of the Venetian Republic.

In 1527, Filippo Catani, owner of the

glasshouse “Alla Sirena” (a name from

which the family of glassmasters derived

the surname it is known by in Venice –

Serena) obtained the “privilege” of a new

glass technique: the refined filigrana a re-

tortoli which along with filigrana a reticel-

lo must be considered the most important

innovations of Sixteenth century Murano

glass. Filigrana was achieved through a so-

phisticated decorative hotwork technique:

thin rods of glass containing a core of

opaque glass threads, were laid down one

beside the other on a slab of refractory

stone, heated by the fire of the furnace un-

til they melted together into a single

piece. The plate of glass thus obtained

was rolled around a transparent and in-

candescent glass cylinder, so that only the

internal threads remained visible, then it

was blown as usual. It was the beginning

of a flourish of glass blown a galea, or

with plumed effects a penne, and dia-

mond-point engravings...

The exquisite crafting of these artifacts

from Murano made the ruling heads and

aristocracy of Europe delirious, so much so

that imitations of glass production “à la

façon de Venise” began to multiply;

Venetian glass masters left the Republic to

open furnaces in London, Antwerp and

Munich, creating important centers of pro-

duction; Andalusia, Catalonia, Sweden,

the Netherlands and the Hapsburg territo-

ries all benefited from the founding of

“Murano” glasshouses.

In Italy the most successful attempts at

replicating Venetian glass production were

made in Tuscany by the Grand Duke

Cosimo I, who was able to coax the

Murano glassmaster Bortolo d’Alvise to his

court in 1569: he worked in the ducal ter-

ritories, and contributed greatly to the

artistic development of Renaissance glass

production.

The Plague erupts,

the glassmasters revolt:

the beginning of the decline

The slow but inexorable decline of

Murano’s magnificent Art began in 1600,

at a time when the skilled hands of the

Venetian masters were still creating pieces

of astounding beauty.

The early part of the century witnessed the

invention of the incalmo technique and of

the sparkling avventurina with its infinite

reflections created by tiny metallic copper

crystals, the product of a sophisticated

cooling process. The production of goblets

was vast and varied, adapted to the taste

and requirements of the most diverse

European clienteles: tall flute glasses for

Holland, saucers as flat as silver platters

for the Italian market...

The XVIIth century was also the century of

tro chiamato cristallo, di considerevole pu-

rezza e trasparenza per l’epoca.

L’invenzione ottenne immediato successo,

proprio mentre andavano perfezionandosi

anche le tecniche decorative dei vetri a

smalto e oro.

Il tramonto del secolo vide l’introduzione

del rosechiero, vetro di un bellissimo rosso

vivo e delle rosette, cilindretti formati da

canne vitree, recanti in sezione motivi de-

corativi. Queste, inserite in lastre di vetro

soffiato anticiparono la più tarda lavora-

zione a murrine, tipica del XIX secolo.

I risultati di tali innovazioni attirarono l’in-

teresse dei principi delle corti europee: i

Medici e gli Sforza furono i primi a cerca-

re di attirare presso di sé i maestri mura-

nesi, nell’intento di dare prestigio artistico

alle proprie dimore.

Il secolo d’oro:

protezionismo

ed imitazione

Fu nel corso del XVI secolo che l’arte mu-

ranese del vetro raggiunse la sua piena

maturità, quando andare “a veder far veri

a Muran” divenne una tappa irrinunciabile

per ogni personalità eminente che facesse

visita a Venezia.

Con il riordino definitivo della Mariegola,

le maestranze muranesi assunsero sempre

maggior peso e il Governo della Serenissima,

che in quegli stessi anni cominciava ad as-

sistere al declino del proprio potere, do-

vette intensificare le politiche di protezio-

nismo volte ad impedire la fuoriuscita del-

le tecniche di lavorazione dal territorio la-

gunare.

Nel 1527 Filippo Catani titolare della for-

nace “Alla Sirena”, (insegna dalla quale

deriva il nome con cui la famiglia di vetrai

è conosciuta in ambito veneziano, ovvero

Serena) ottenne il privilegio per un nuovo

tipo di lavorazione del vetro: la raffinata

tecnica della filigrana a retortoli che costi-

tuì, insieme alla filigrana a reticello la più

importante novità della vetraria veneziana

cinquecentesca. La filigrana era ottenuta

tramite una sofisticata tecnica decorativa a

caldo: sottili canne di vetro contenenti

un’anima di fili in vetro opaco, venivano

accostate le une alle altre su una piastra

refrattaria, scaldate al fuoco della fornace

fino a fondersi e unirsi tra loro. La piastra

ottenuta era avvolta intorno ad un cilindro

vitreo trasparente e incandescente, in mo-

do che risultassero visibili i soli fili interni,

quindi si procedeva alla consueta soffiatu-

14

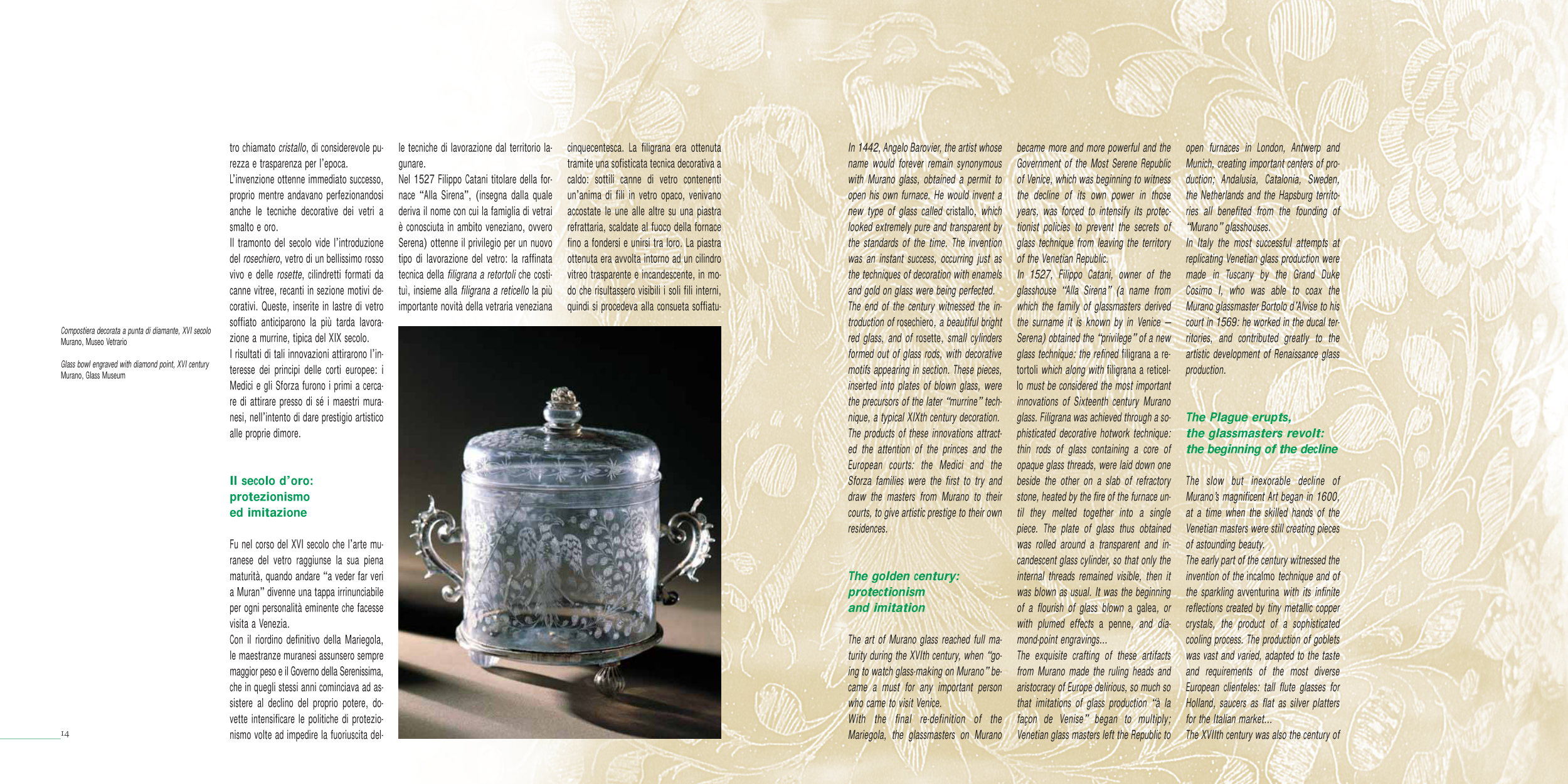

Compostiera decorata a punta di diamante, XVI secolo

Murano, Museo Vetrario

Glass bowl engraved with diamond point, XVI century

Murano, Glass Museum