G.T.

G.T.

G.T.

which is what we are aiming for in all our buildings,

it is necessary to know all the potentials of the

site, energy potentials that are given not only by

the sun, which I have already mentioned, but also

by the geothermal potential of the ground, by the

winds and by the trees that provide shade: so the

context means, as it used to mean out of necessity,

being able to optimise the energy performance of a

building in relation to the potential of the site. So

yes, I believe that context has a double value: an

energetic one and a qualitative one, which is also

linked to the well-being of the occupants.

What are the design challenges of integrating

natural light with its artificial component, and how

well is today’s technology able to merge the two?

The challenges lie precisely in the word integration,

i.e. trying to make artificial light more and more like

natural light, so that it can gradually replace it in

terms of both intensity and quality, so that it can

be as warm as the sun or as cold as the sky, and

so that it can change. I think this is a very topical

issue. All the new solid-state technologies, more

commonly known as LEDs, combined with the

ever-increasing proliferation of control systems,

expressed through the programmability of light and

the use of sensors, allow light to become a positive

light for people again. Artificial light, as revolutionary

as it has been in prolonging human life in the dark,

has in turn conditioned its quality because it has

been static light, often glaring, with a constant

colour temperature. I think first of tungsten, then

fluorescent, then discharge, and so on. The LEDs,

on the other hand, by its very nature, is an electronic

component, so it is easily modifiable, and I think

it is precisely in this modifiability that it can play

its strength, and in many of our projects we have

experimented with precisely this possibility of using

the LEDs as a continuous integration as an emulation

of natural light. It can work for emulation in closed

office spaces and it can also work for integration in

strongly naturally lit daylight spaces.

On the subject of raising awareness of spaces

where light plays an increasingly important role

in people’s well-being, what role can brands play

on of this aspect, which is very often neglected by

designers?

What I hope is that lighting brands will be able to

embrace this change and the need for a change

of perspective, from light measured in Lumens to

light measured in quality. It is no longer so much

a question of being able to make the most efficient

lamp possible, as the best engineers would do

with monochromatic light in the greatest quantity,

but of being able to give priority to well-being, to

modulation, also because in reality we all work more

and more in front of a screen in situations where we

already have the light, it is already inside the device

we are working with.

From micro to macro, from residential to

commercial, the scalability of a process is essential.

How does the design methodology change, if at all,

depending on these aspects?

No, I don’t think it changes, and the beauty of our

work is that it’s multi-scale, where micro and macro

constantly mix at different levels and scales, but the

method is always the same. Designing a small space

or a large space always follows the same rules of

analysis and synthesis that are part of the design

process, so the attention and priorities are always

the same, so yes, only the scale changes.

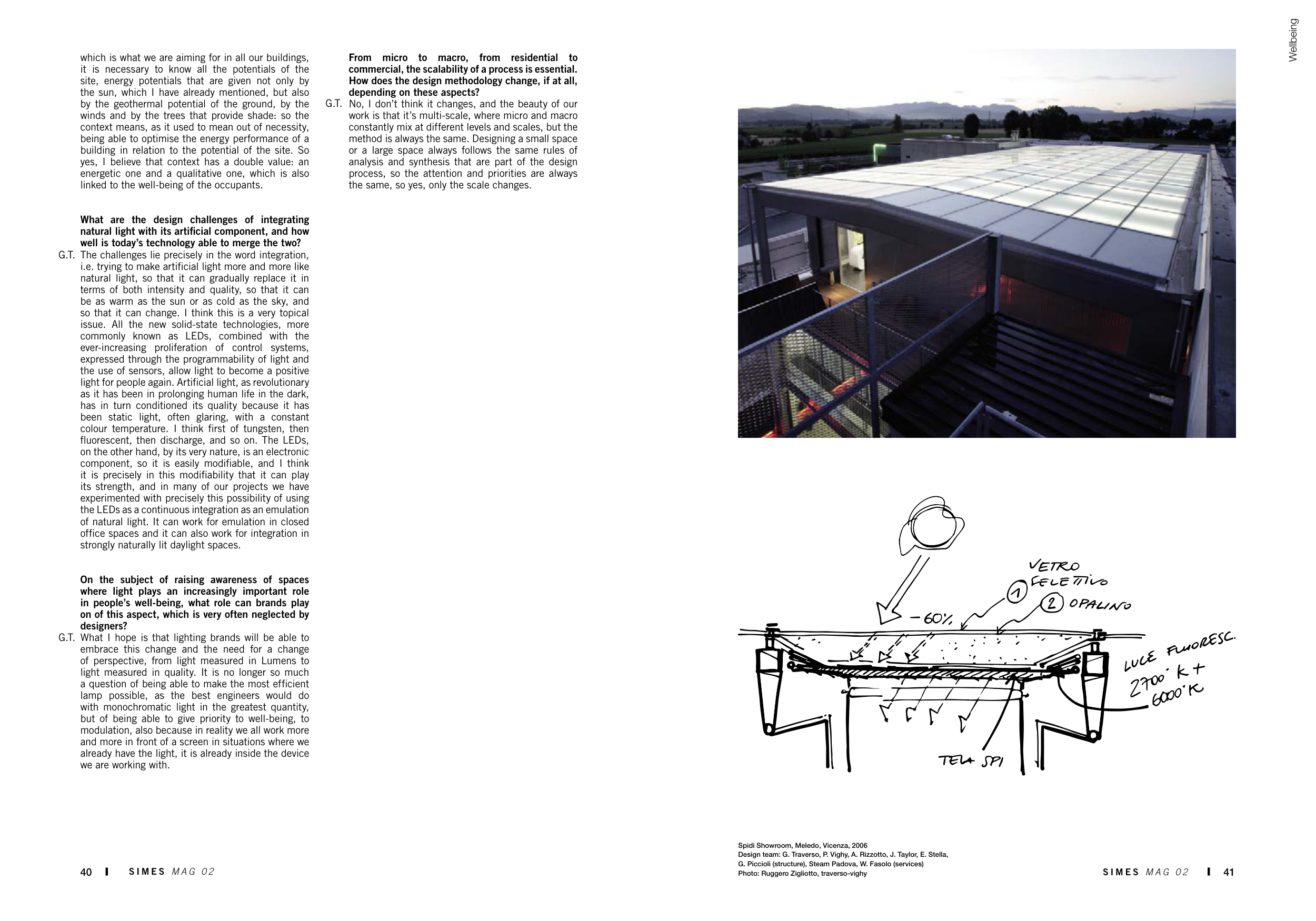

Spidi Showroom, Meledo, Vicenza, 2006

Design team: G. Traverso, P. Vighy, A. Rizzotto, J. Taylor, E. Stella,

G. Piccioli (structure), Steam Padova, W. Fasolo (services)

Photo: Ruggero Zigliotto, traverso-vighy

Wellbeing

40

41

S I M E S M A G 0 2

S I M E S M A G 0 2