Wellbeing

How did the different lights of the countries you

visited sound differently in your perception? Did

they affect your knowledge of light?

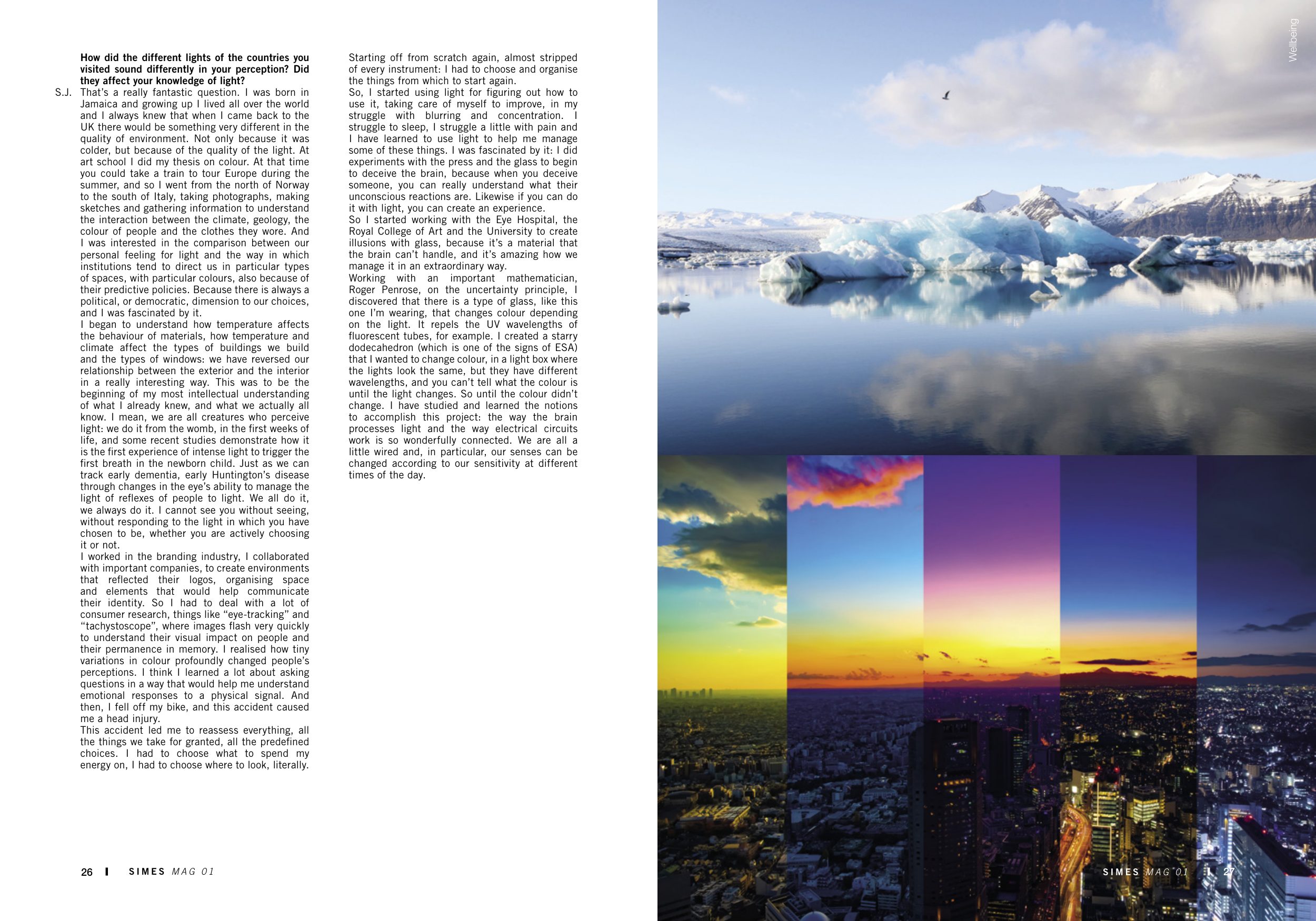

That’s a really fantastic question. I was born in

Jamaica and growing up I lived all over the world

and I always knew that when I came back to the

UK there would be something very different in the

quality of environment. Not only because it was

colder, but because of the quality of the light. At

art school I did my thesis on colour. At that time

you could take a train to tour Europe during the

summer, and so I went from the north of Norway

to the south of Italy, taking photographs, making

sketches and gathering information to understand

the interaction between the climate, geology, the

colour of people and the clothes they wore. And

I was interested in the comparison between our

personal feeling for light and the way in which

institutions tend to direct us in particular types

of spaces, with particular colours, also because of

their predictive policies. Because there is always a

political, or democratic, dimension to our choices,

and I was fascinated by it.

I began to understand how temperature affects

the behaviour of materials, how temperature and

climate affect the types of buildings we build

and the types of windows: we have reversed our

relationship between the exterior and the interior

in a really interesting way. This was to be the

beginning of my most intellectual understanding

of what I already knew, and what we actually all

know. I mean, we are all creatures who perceive

light: we do it from the womb, in the first weeks of

life, and some recent studies demonstrate how it

is the first experience of intense light to trigger the

first breath in the newborn child. Just as we can

track early dementia, early Huntington’s disease

through changes in the eye’s ability to manage the

light of reflexes of people to light. We all do it,

we always do it. I cannot see you without seeing,

without responding to the light in which you have

chosen to be, whether you are actively choosing

it or not.

I worked in the branding industry, I collaborated

with important companies, to create environments

that reflected their logos, organising space

and elements that would help communicate

their identity. So I had to deal with a lot of

consumer research, things like “eye-tracking” and

“tachystoscope”, where images flash very quickly

to understand their visual impact on people and

their permanence in memory. I realised how tiny

variations in colour profoundly changed people’s

perceptions. I think I learned a lot about asking

questions in a way that would help me understand

emotional responses to a physical signal. And

then, I fell off my bike, and this accident caused

me a head injury.

This accident led me to reassess everything, all

the things we take for granted, all the predefined

choices. I had to choose what to spend my

energy on, I had to choose where to look, literally.

S.J.

Starting off from scratch again, almost stripped

of every instrument: I had to choose and organise

the things from which to start again.

So, I started using light for figuring out how to

use it, taking care of myself to improve, in my

struggle with blurring and concentration. I

struggle to sleep, I struggle a little with pain and

I have learned to use light to help me manage

some of these things. I was fascinated by it: I did

experiments with the press and the glass to begin

to deceive the brain, because when you deceive

someone, you can really understand what their

unconscious reactions are. Likewise if you can do

it with light, you can create an experience.

So I started working with the Eye Hospital, the

Royal College of Art and the University to create

illusions with glass, because it’s a material that

the brain can’t handle, and it’s amazing how we

manage it in an extraordinary way.

Working with an important mathematician,

Roger Penrose, on the uncertainty principle, I

discovered that there is a type of glass, like this

one I’m wearing, that changes colour depending

on the light. It repels the UV wavelengths of

fluorescent tubes, for example. I created a starry

dodecahedron (which is one of the signs of ESA)

that I wanted to change colour, in a light box where

the lights look the same, but they have different

wavelengths, and you can’t tell what the colour is

until the light changes. So until the colour didn’t

change. I have studied and learned the notions

to accomplish this project: the way the brain

processes light and the way electrical circuits

work is so wonderfully connected. We are all a

little wired and, in particular, our senses can be

changed according to our sensitivity at different

times of the day.

27

S I M E S M A G 0 1

26

S I M E S M A G 0 1