We are often used to thinking of architecture

as something sculptural, linked to our historical

heritage, a form that is almost immutable in time.

In your projects (Studio Traverso-Vighy), on the

other hand, an approach emerges that you define as

“reversibility” applied to architecture, almost as if it

were a living organism.

Could you describe how this circular vision of yours

has developed?

I believe this vision has matured over time, starting

from our formative years and then perfected in our

more recent works, which are also the most radical

in this sense. I think it all started with the generation

to which I belong. Born in ‘69 and graduated in ‘94,

I grew up in a world that had mainly developed in the

twenty to thirty years following an explosive building

boom. Indeed, about 80% of italian construction

can be attributed to the period after the Second

World War.

Perhaps it derives from an “allergy” to this

cementification

and,

conversely,

a

sensitive

appreciation for the landscape of my territory. I

come from a small city, Vicenza, where there are

open spaces, mountains, hills, intact environments

that have often been contaminated by this trend.

Probably unconsciously, even in our studies, we have

always sought an antidote to this cementification.

Both Paola Vighy and I (ed. Traverso-Vighy studio)

graduated in architecture at the Iuav University

of Venice and later studied in London at Bartlett

University where we learned an architecture thought

more for “craft pieces” and components typical of

the entire strand of English architecture of those

years and where we followed a master’s course in

Light & Lighting. Returning to Italy, we opened our

studio in a very fertile situation characterized by a

very flexible economy made up of small enterprises

where it was possible to produce any piece with high

technology at relatively low costs. We experimented

with the first non-traditional buildings. To construct

our first architectures, bricks, mortar, or plasterboard

were not needed, but a dry assembly of predefined

components.

Then, over the years, the use of computers has

become increasingly predominant in the studio,

and this architecture has become digital, making it

possible to control the single piece, build it three-

dimensionally, and arrive, as it has been precisely

in the latest projects of the studio, to produce

everything with a perfectly digital method. We

applied this process to traditional materials because

traditional architecture, which by definition is made

of local materials available within a small radius

from the construction site, relies on materials like

larch wood from the mountains, steel from local

carpentries, glass, and stone from the territory.

All materials workable with CNC numerical control

or laser cutting. We are talking, therefore, about

automatic processes on traditional materials, of

which we have tried to resume the use and the

knowledge of processing and finishing. For example,

wood that dries when it rains to avoid treatments

or varnishes also for the love of what John Ruskin

called “patina”, i.e., that thing that attacks the

materials and makes them able to merge with the

environment.

Thus, the first buildings were of this type, and then

little by little, we developed our path, our current in

G.T.

a perspective of recycling materials from buildings

at the end of life. I think about glass, aluminium, or

steel, or materials that can also be directly reused,

such as wooden beams and planks. So yes, perhaps

our buildings are somewhat of an organism.

I believe this is a way of proceeding in continuity

with the environment. It is a way that joins a word

very much in vogue today, which is circularity. I

hope that this method of work can be as ethical as

possible and become an example to share with the

people we collaborate with.

Also, our working system is crucial: we design

everything in the design phase. No choice is made on

the construction site because everything is already

predetermined in the project phase, in which all our

internal and external collaborators at the studio,

including engineers, structuralists, mechanics,

electricians, geologists, or surveyors, participate.

Very often, in this phase, we consult craftsmen who

make prototypes, we fine-tune them, and then in the

executive design, the finished product appears. This

very detailed design also allows cost control, i.e.,

offers as a whole “bypassing” as much as possible

the traditional accounting of a construction site and

the arising of economies. This has led to progressive

growth for clients and the studio with increasingly

ambitious commissions.

“There’s no place like another”, to borrow from

Dorothy’s famous line in “The Wizard of Oz”, to

what extent does context influence design choices

to create buildings designed for human wellbeing?

The context totally influences the design choices.

Naturally, the ideal situation would be to have a

house on top of a hill, surrounded by nature 360°,

like in the Renaissance. In our time, however, we

have to somehow carve out the context, because in

architectural terms, context means views and points

to look at. Context is also exposure and orientation

to the sun, because passive buildings, like the ones

we design, have to make the best use of the sun

throughout the seasons, to warm in winter and stay

cool in summer. For this reason they need a sensible

exposure to the sun. The design of the building

envelope in relation to the context is important

because it determines the relationship between

the occupant and the external environment. We

strongly believe in the concept of circadianity, i.e.

the fact that people live and work in an “external”

environment even though they are inside a case.

It is well known that in modern civilisation one of the

stress problems for many people is precisely the fact

that we are more and more in enclosed spaces, in

means of transport, in the presence of artificial light,

losing contact with the seasons, with meteorology,

with the variations and modulations of light, which

are instead extremely positive in regulating our

biorhythms for our well-being. This is therefore an

aspect common to all our buildings, where we always

try to have or recreate a contact with the outside,

which can be horizontal towards the garden, towards

a valley, but also, as in some projects such as the

“Spidi Sport Showroom”, open upwards towards the

sky, just by capturing the modulations of light.

The context can also have another level of reasoning,

which in our case started from the project of our

studio in 2011. For a building to be zero energy,

G.T.

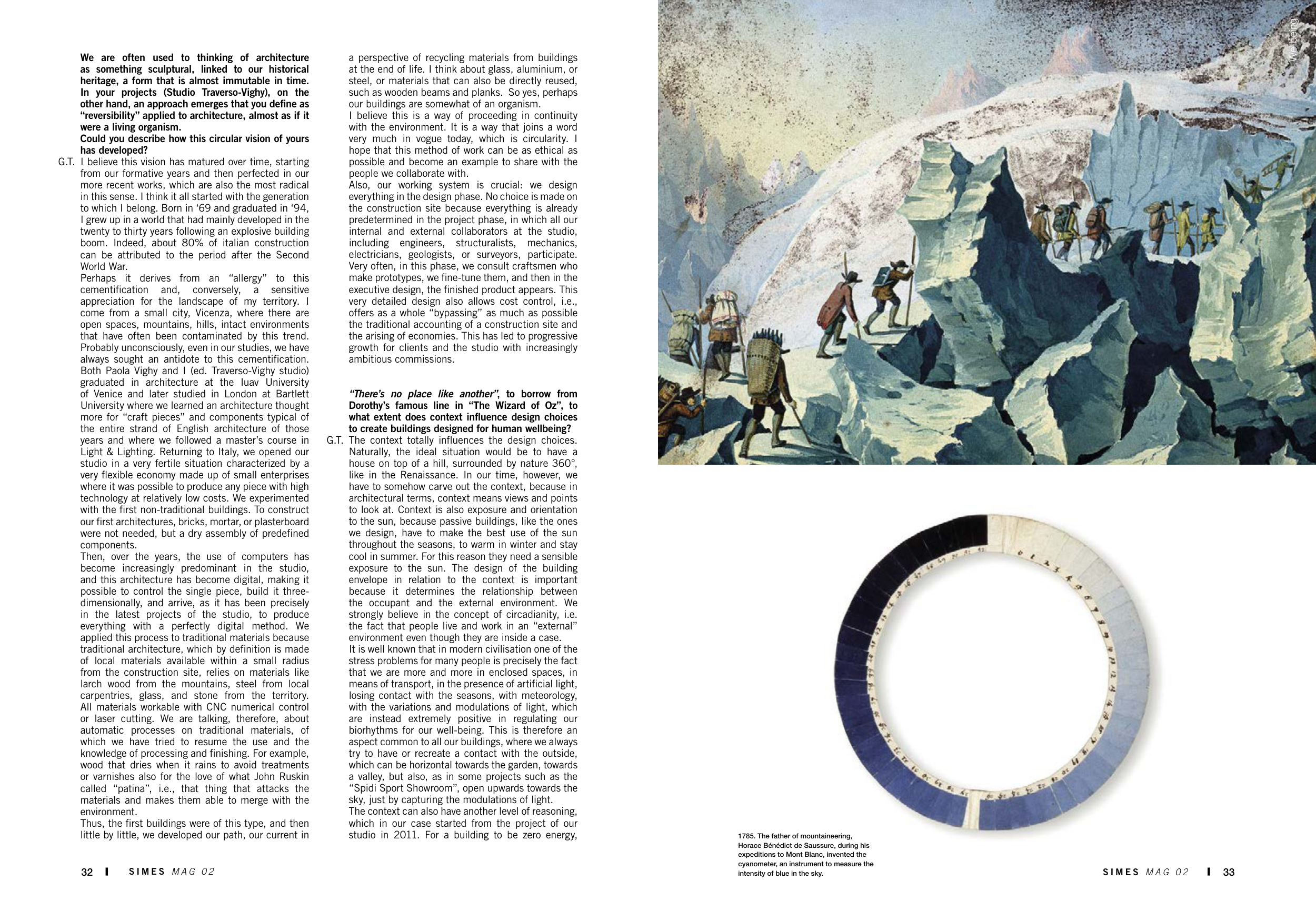

1785. The father of mountaineering,

Horace Bénédict de Saussure, during his

expeditions to Mont Blanc, invented the

cyanometer, an instrument to measure the

intensity of blue in the sky.

Wellbeing

32

33

S I M E S M A G 0 2

S I M E S M A G 0 2