07 • MOSAICS IN THE RENAISSANCE

In the Renaissance, mosaics are no longer independent creative mediums, they become virtuosity: the only interest is for the

apparent eternity of the mosaic material to immortalize paintings, so much so that Ghirlandaio considers the mosaic as true

painting for eternity, and Vasari praises the mosaicists that mimic painting to the point of deceiving the viewer.

In this period, many artists provide cartons to be translated into mosaic: Ghirlandaio, Mantegna, Tintoretto, and Veronese.

The greatest mosaic work of the Renaissance is in the church of San Marco in Venice: it is a votive offering of the Doge Foscari and

includes works by Andrea del Castagno and Jacopo Bellini.

In the fourteenth century, mosaics are also used as a support for sculptural works by Arnolfo di Cambio, in which the mosaic gives

greater prominence to the bas-reliefs. (pic.07: Orvieto ’s cathedral)

08 • MOSAICS IN THE BAROQUE

From the Mannerist period up to the Rococo period, spreads a mosaic technique taken from Imperial Rome, with cobblestone

mosaics or other natural elements such as shells, spongy rocks, stalactites, and semiprecious stones. These imaginative creations

originated in Florence at the hands of great artists and soon spread throughout Europe.

In the Baroque period mosaics become an art definitely subordinated to architecture and painting, often used as floor coverings

or mainly on the facades of buildings.

It also extends to ornaments, especially with the inclusion of semiprecious stones or with the recovery of antique mosaics, which

are transformed into table tops or inserted in floor decorations.

Roma is in first place for mosaic decorations, as a source of patronage for the local mosaic art school. In 1727, the Studio del

Mosaico Vaticano is established, which promotes research in the production of glass paste. They produced up to 15,300 different

shades of opaque glazes. The most significant results are achieved in glaze production, with the spinning of glass paste in sticks to

obtain very small tesserae, even smaller than a millimetre, with colour gradients, called ‘malmischiati’ (badly mixed).

The ‘mosaici minuti’ (minute mosaics) are born, to mimic and replace paintings with great refinement and virtuosity; they will later

be used also in the decoration of ornaments and jewels. (pic.08: II Pozzino villa, Florence)

09 • MOSAICS IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY

In the neoclassical period, mosaics, although an important art form of classicism, were almost completely abandoned because of

the influence of the ‘major’ arts such as painting, sculpture, and architecture.

It was only in the Romantic period that artistic techniques taken from the medieval world came back to popularity, including

stained glass, carving, and, indeed, mosaics. Among the neo-medieval mosaics, with an archaizing gold background but with

vivid drawing typical of nineteenth-century design, stand out the works for the restructuring and the ‘restoration’ of churches and

cathedrals.

In the nineteenth century, faster and less expensive techniques are developed: the indirect method is born, which consists in

creating the mosaic on a sheet of paper, backwards, to then place it in situ. The economic advantages, which are shorter processing

times and lower costs, allow the realization of facades or large surfaces such as the decoration of the facade of Palazzo Barbarigo

on the Grand Canal made in 1886. (pic.09: Barbarigo palace, Venice)

10 • MOSAICS IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY

Antoni Gaudí

The eclectic style of the Catalan architect mixes Gothic and Renaissance shapes with experimental materials and decorations. He

proposes new mosaic applications, inserting fragments of coloured stones, marbles, glazes, and ceramics, covering also three-

dimensional objects, following the example of the Aztec culture.

Irregularly cut pieces of glass and ceramics, following the trencadís technique, which is a re-elaboration of the Arab ceramic

mosaic, cover every surface, resulting in violent chromatic effects: improbable architectures thus assume dreamlike characteristics

that exalt the playful and surreal shapes.

Gustav Klimt

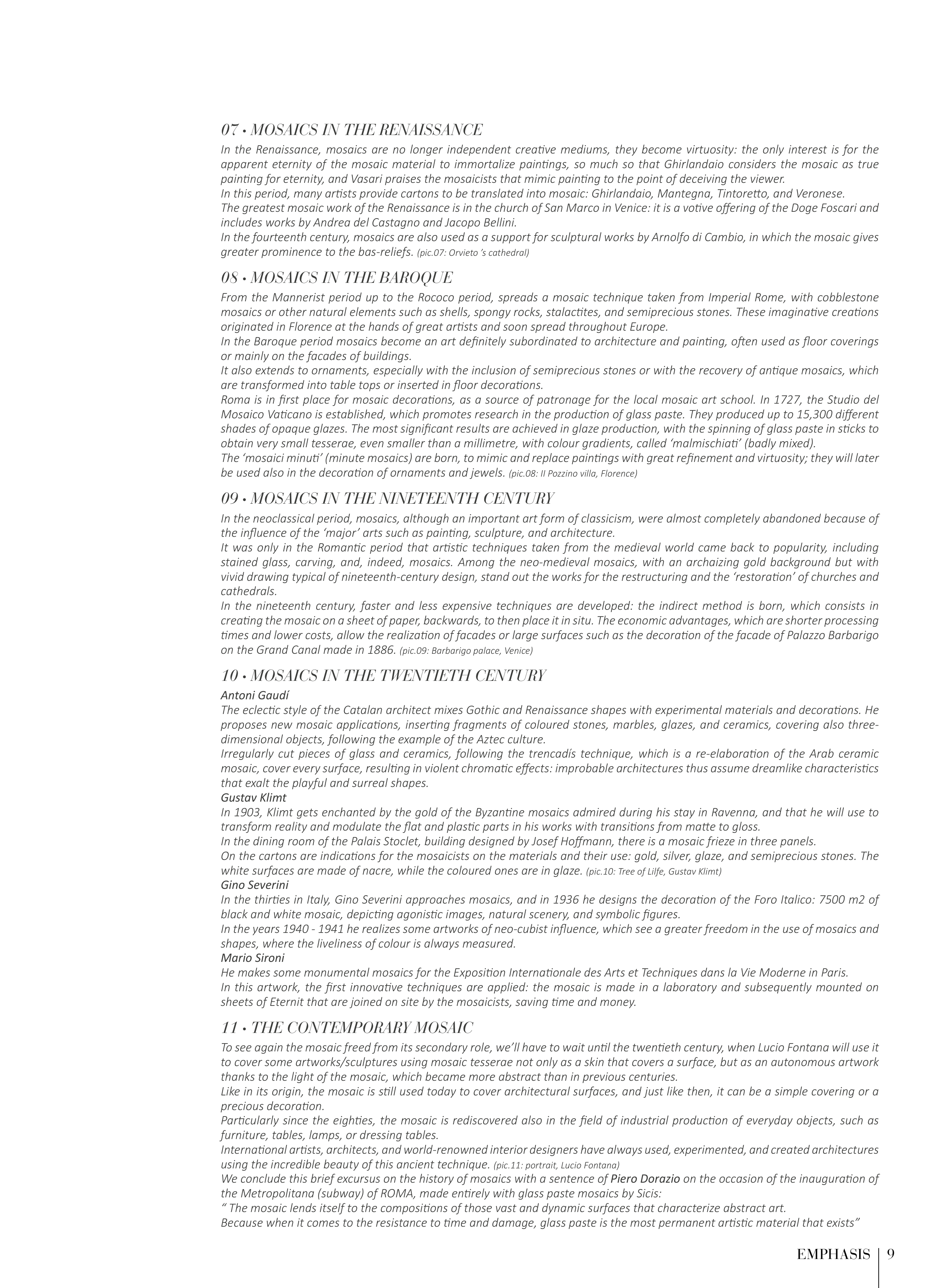

In 1903, Klimt gets enchanted by the gold of the Byzantine mosaics admired during his stay in Ravenna, and that he will use to

transform reality and modulate the flat and plastic parts in his works with transitions from matte to gloss.

In the dining room of the Palais Stoclet, building designed by Josef Hoffmann, there is a mosaic frieze in three panels.

On the cartons are indications for the mosaicists on the materials and their use: gold, silver, glaze, and semiprecious stones. The

white surfaces are made of nacre, while the coloured ones are in glaze. (pic.10: Tree of Lilfe, Gustav Klimt)

Gino Severini

In the thirties in Italy, Gino Severini approaches mosaics, and in 1936 he designs the decoration of the Foro Italico: 7500 m2 of

black and white mosaic, depicting agonistic images, natural scenery, and symbolic figures.

In the years 1940 - 1941 he realizes some artworks of neo-cubist influence, which see a greater freedom in the use of mosaics and

shapes, where the liveliness of colour is always measured.

Mario Sironi

He makes some monumental mosaics for the Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne in Paris.

In this artwork, the first innovative techniques are applied: the mosaic is made in a laboratory and subsequently mounted on

sheets of Eternit that are joined on site by the mosaicists, saving time and money.

11 • THE CONTEMPORARY MOSAIC

To see again the mosaic freed from its secondary role, we’ll have to wait until the twentieth century, when Lucio Fontana will use it

to cover some artworks/sculptures using mosaic tesserae not only as a skin that covers a surface, but as an autonomous artwork

thanks to the light of the mosaic, which became more abstract than in previous centuries.

Like in its origin, the mosaic is still used today to cover architectural surfaces, and just like then, it can be a simple covering or a

precious decoration.

Particularly since the eighties, the mosaic is rediscovered also in the field of industrial production of everyday objects, such as

furniture, tables, lamps, or dressing tables.

International artists, architects, and world-renowned interior designers have always used, experimented, and created architectures

using the incredible beauty of this ancient technique. (pic.11: portrait, Lucio Fontana)

We conclude this brief excursus on the history of mosaics with a sentence of Piero Dorazio on the occasion of the inauguration of

the Metropolitana (subway) of ROMA, made entirely with glass paste mosaics by Sicis:

“ The mosaic lends itself to the compositions of those vast and dynamic surfaces that characterize abstract art.

Because when it comes to the resistance to time and damage, glass paste is the most permanent artistic material that exists”

9

EMPHASIS