portare l’attenzione dello spettatore sulla realtà dell’Ignoto,

sulla contemplazione dell’Universo, su quello che c’è oltre la

Terra. Cambia ancora il rapporto tra l’Uomo e la Natura con

Caravaggio, che spinge la sua ricerca in un’altra direzione. Con

la Canestra di frutta (1597-98) della Pinacoteca Ambrosiana

di Milano, il maestro della luce vuole che i protagonisti della

sua opera siano frutti troppo maturi, già intaccati dagli insetti

e con le foglie rinsecchite: una mela bacata, un fico spaccato,

acini d’uva qua e là appassiti. E così, usando l’allegoria del

Memento Mori, attraverso i segni del decadimento, l’artista ci

ricorda che anche l’Uomo è un essere mortale, e la sua esistenza

è effimera, breve quanto foglie

e frutti. Facendo nascere il

genere della Natura Morta,

Caravaggio ci vuole mettere in

guardia dai rischi della Vanitas.

Ora, con un salto temporale di

qualche secolo, arriviamo alla

rappresentazione della Natura

nell’Arte

contemporanea.

E

così ci rendiamo conto che

questa è oggi testimonianza

di qualcosa di compromesso,

segno di un dissolvimento

inarrestabile. Le opere, spesso

affidate alla forza d’impatto

della fotografia, ci restituiscono

la verità delle ferite inflitte

dall’Uomo al Pianeta. La ricerca

artistica passa dal particolare al

generale: se quattro secoli fa

la fugacità della vita umana era

espressa attraverso una foglia

avvizzita e un frutto marcio,

oggi la minaccia al futuro della

Natura ha l’impatto di immagini

prese dall’alto che mostrano centinaia di ettari di territorio

devastati. La morale, neanche troppo velata, è che l’Uomo ha

depredato senza riguardi quello che non ha mai considerato il

suo giardino, spingendosi a un punto di non ritorno. E l’arte va

a indagare le prove della sua colpevolezza. Un primo esempio

viene da Vik Muniz, artista brasiliano che lavora da trent’anni

con materiali di scarto, spesso usando montagne di spazzatura.

Il suo progetto Waste Land, un documentario girato per tre

anni all’interno di Jardim Gramacho, la più grande discarica

a cielo aperto del Sudamerica, ha dato origine ai Pictures of

Garbage, ovvero riproduzioni gigantesche di capolavori della

storia dell’arte fatte di rifiuti. Come il celebre quadro de La

Morte di Marat di Jacques-Louis David, assemblato con l’aiuto

paziente dei catadores, che recuperano tra i rifiuti quel poco che

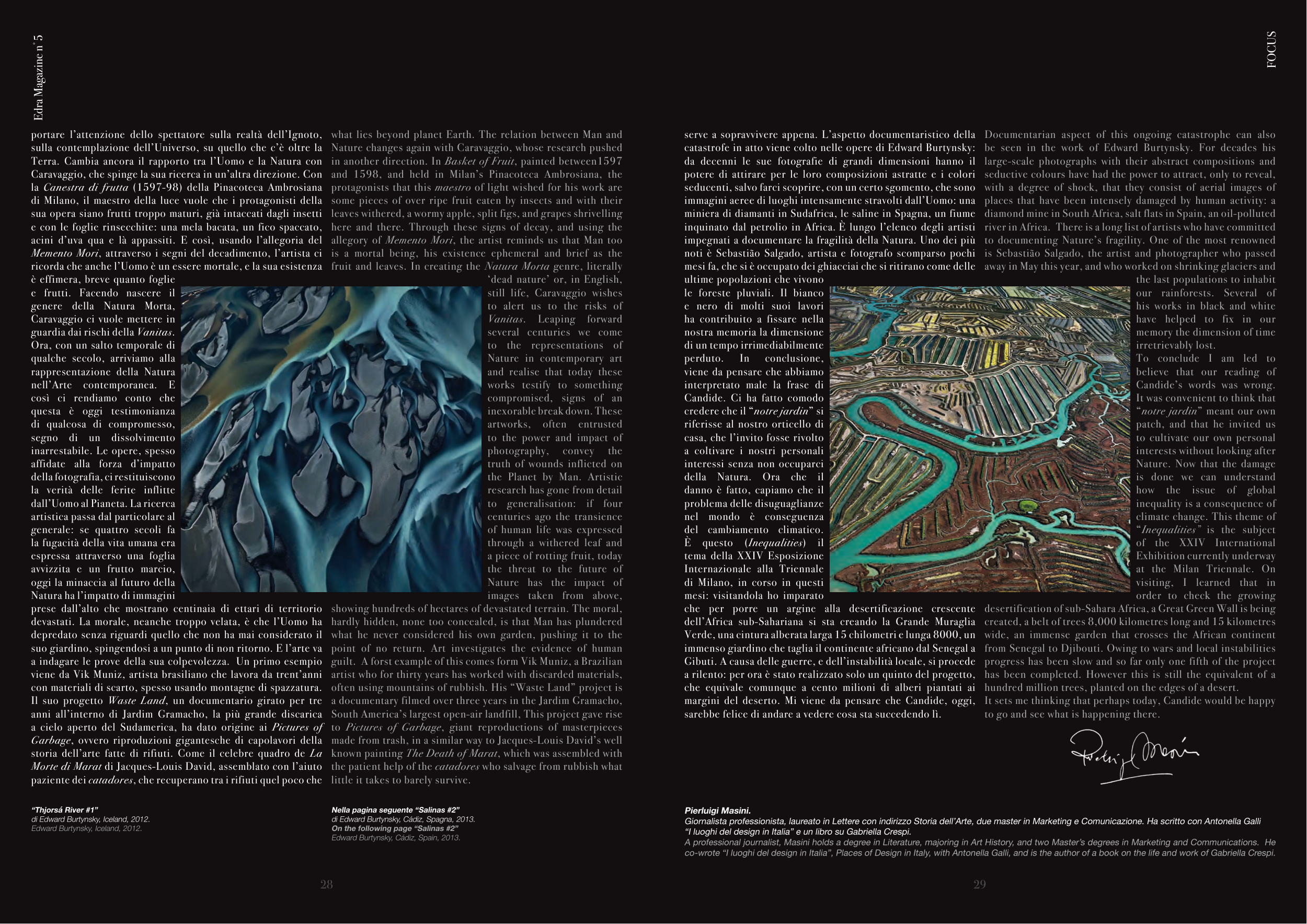

serve a sopravvivere appena. L’aspetto documentaristico della

catastrofe in atto viene colto nelle opere di Edward Burtynsky:

da decenni le sue fotografie di grandi dimensioni hanno il

potere di attirare per le loro composizioni astratte e i colori

seducenti, salvo farci scoprire, con un certo sgomento, che sono

immagini aeree di luoghi intensamente stravolti dall’Uomo: una

miniera di diamanti in Sudafrica, le saline in Spagna, un fiume

inquinato dal petrolio in Africa. È lungo l’elenco degli artisti

impegnati a documentare la fragilità della Natura. Uno dei più

noti è Sebastião Salgado, artista e fotografo scomparso pochi

mesi fa, che si è occupato dei ghiacciai che si ritirano come delle

ultime popolazioni che vivono

le foreste pluviali. Il bianco

e nero di molti suoi lavori

ha contribuito a fissare nella

nostra memoria la dimensione

di un tempo irrimediabilmente

perduto.

In

conclusione,

viene da pensare che abbiamo

interpretato male la frase di

Candide. Ci ha fatto comodo

credere che il “notre jardin” si

riferisse al nostro orticello di

casa, che l’invito fosse rivolto

a coltivare i nostri personali

interessi senza non occuparci

della Natura. Ora che il

danno è fatto, capiamo che il

problema delle disuguaglianze

nel mondo è conseguenza

del cambiamento climatico.

È

questo

(Inequalities)

il

tema della XXIV Esposizione

Internazionale alla Triennale

di Milano, in corso in questi

mesi: visitandola ho imparato

che per porre un argine alla desertificazione crescente

dell’Africa sub-Sahariana si sta creando la Grande Muraglia

Verde, una cintura alberata larga 15 chilometri e lunga 8000, un

immenso giardino che taglia il continente africano dal Senegal a

Gibuti. A causa delle guerre, e dell’instabilità locale, si procede

a rilento: per ora è stato realizzato solo un quinto del progetto,

che equivale comunque a cento milioni di alberi piantati ai

margini del deserto. Mi viene da pensare che Candide, oggi,

sarebbe felice di andare a vedere cosa sta succedendo lì.

Pierluigi Masini.

Giornalista professionista, laureato in Lettere con indirizzo Storia dell’Arte, due master in Marketing e Comunicazione. Ha scritto con Antonella Galli

“I luoghi del design in Italia” e un libro su Gabriella Crespi.

A professional journalist, Masini holds a degree in Literature, majoring in Art History, and two Master’s degrees in Marketing and Communications. He

co-wrote “I luoghi del design in Italia”, Places of Design in Italy, with Antonella Galli, and is the author of a book on the life and work of Gabriella Crespi.

“Thjorsá River #1”

di Edward Burtynsky, Iceland, 2012.

Edward Burtynsky, Iceland, 2012.

Nella pagina seguente “Salinas #2”

di Edward Burtynsky, Cádiz, Spagna, 2013.

On the following page “Salinas #2”

Edward Burtynsky, Cádiz, Spain, 2013.

what lies beyond planet Earth. The relation between Man and

Nature changes again with Caravaggio, whose research pushed

in another direction. In Basket of Fruit, painted between1597

and 1598, and held in Milan’s Pinacoteca Ambrosiana, the

protagonists that this maestro of light wished for his work are

some pieces of over ripe fruit eaten by insects and with their

leaves withered, a wormy apple, split figs, and grapes shrivelling

here and there. Through these signs of decay, and using the

allegory of Memento Mori, the artist reminds us that Man too

is a mortal being, his existence ephemeral and brief as the

fruit and leaves. In creating the Natura Morta genre, literally

‘dead nature’ or, in English,

still life, Caravaggio wishes

to alert us to the risks of

Vanitas.

Leaping

forward

several centuries we come

to the representations of

Nature in contemporary art

and realise that today these

works testify to something

compromised, signs of an

inexorable break down. These

artworks,

often

entrusted

to the power and impact of

photography,

convey

the

truth of wounds inflicted on

the Planet by Man. Artistic

research has gone from detail

to generalisation: if four

centuries ago the transience

of human life was expressed

through a withered leaf and

a piece of rotting fruit, today

the threat to the future of

Nature has the impact of

images taken from above,

showing hundreds of hectares of devastated terrain. The moral,

hardly hidden, none too concealed, is that Man has plundered

what he never considered his own garden, pushing it to the

point of no return. Art investigates the evidence of human

guilt. A forst example of this comes form Vik Muniz, a Brazilian

artist who for thirty years has worked with discarded materials,

often using mountains of rubbish. His “Waste Land” project is

a documentary filmed over three years in the Jardim Gramacho,

South America’s largest open-air landfill, This project gave rise

to Pictures of Garbage, giant reproductions of masterpieces

made from trash, in a similar way to Jacques-Louis David’s well

known painting The Death of Marat, which was assembled with

the patient help of the catadores who salvage from rubbish what

little it takes to barely survive.

Documentarian aspect of this ongoing catastrophe can also

be seen in the work of Edward Burtynsky. For decades his

large-scale photographs with their abstract compositions and

seductive colours have had the power to attract, only to reveal,

with a degree of shock, that they consist of aerial images of

places that have been intensely damaged by human activity: a

diamond mine in South Africa, salt flats in Spain, an oil-polluted

river in Africa. There is a long list of artists who have committed

to documenting Nature’s fragility. One of the most renowned

is Sebastião Salgado, the artist and photographer who passed

away in May this year, and who worked on shrinking glaciers and

the last populations to inhabit

our rainforests. Several of

his works in black and white

have helped to fix in our

memory the dimension of time

irretrievably lost.

To conclude I am led to

believe that our reading of

Candide’s words was wrong.

It was convenient to think that

“notre jardin” meant our own

patch, and that he invited us

to cultivate our own personal

interests without looking after

Nature. Now that the damage

is done we can understand

how

the

issue

of

global

inequality is a consequence of

climate change. This theme of

“Inequalities” is the subject

of the XXIV International

Exhibition currently underway

at the Milan Triennale. On

visiting, I learned that in

order to check the growing

desertification of sub-Sahara Africa, a Great Green Wall is being

created, a belt of trees 8,000 kilometres long and 15 kilometres

wide, an immense garden that crosses the African continent

from Senegal to Djibouti. Owing to wars and local instabilities

progress has been slow and so far only one fifth of the project

has been completed. However this is still the equivalent of a

hundred million trees, planted on the edges of a desert.

It sets me thinking that perhaps today, Candide would be happy

to go and see what is happening there.

Edra Magazine n°5

28

29

FOCUS