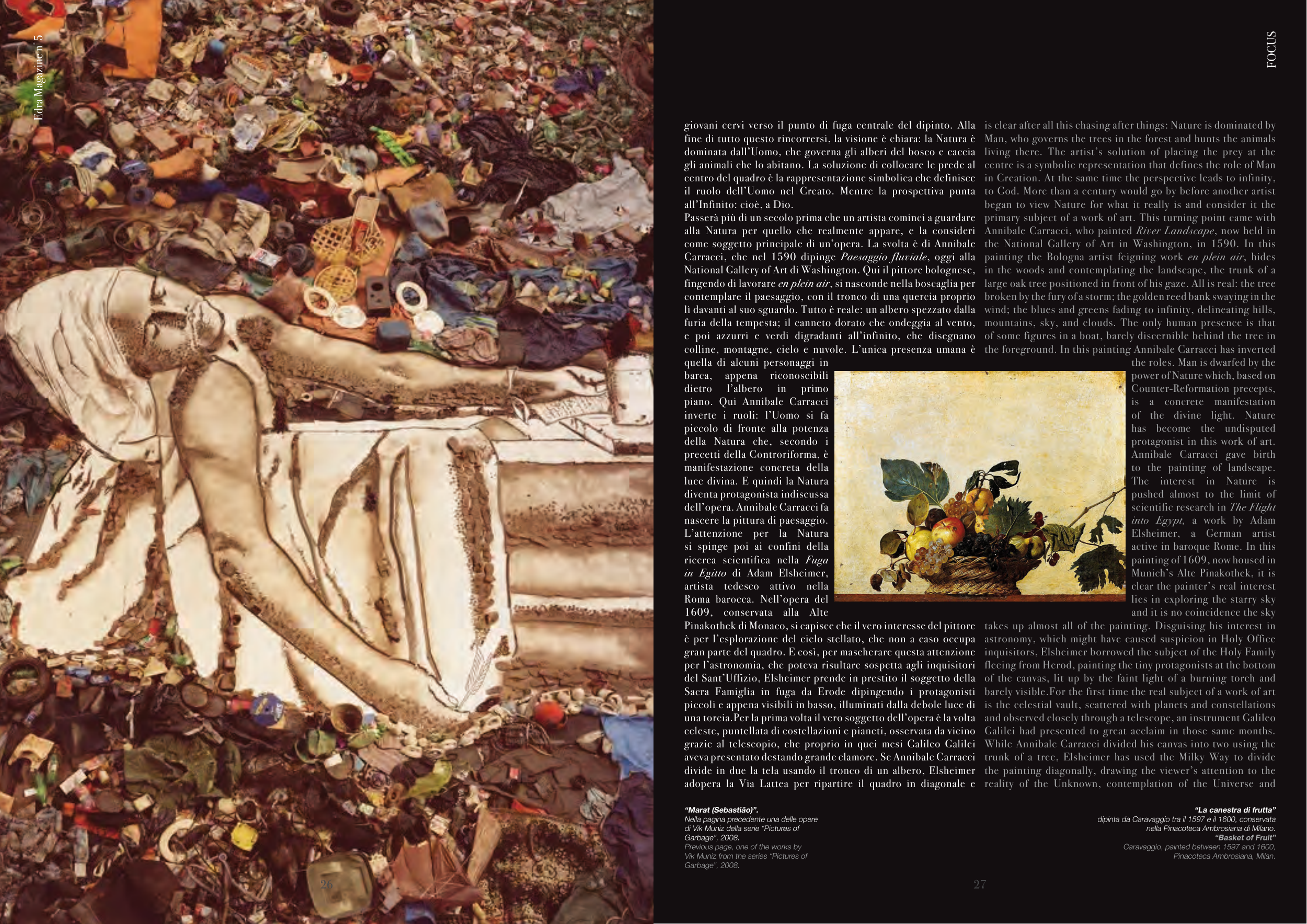

“La canestra di frutta”

dipinta da Caravaggio tra il 1597 e il 1600, conservata

nella Pinacoteca Ambrosiana di Milano.

“Basket of Fruit”

Caravaggio, painted between 1597 and 1600,

Pinacoteca Ambrosiana, Milan.

giovani cervi verso il punto di fuga centrale del dipinto. Alla

fine di tutto questo rincorrersi, la visione è chiara: la Natura è

dominata dall’Uomo, che governa gli alberi del bosco e caccia

gli animali che lo abitano. La soluzione di collocare le prede al

centro del quadro è la rappresentazione simbolica che definisce

il ruolo dell’Uomo nel Creato. Mentre la prospettiva punta

all’Infinito: cioè, a Dio.

Passerà più di un secolo prima che un artista cominci a guardare

alla Natura per quello che realmente appare, e la consideri

come soggetto principale di un’opera. La svolta è di Annibale

Carracci, che nel 1590 dipinge Paesaggio fluviale, oggi alla

National Gallery of Art di Washington. Qui il pittore bolognese,

fingendo di lavorare en plein air, si nasconde nella boscaglia per

contemplare il paesaggio, con il tronco di una quercia proprio

lì davanti al suo sguardo. Tutto è reale: un albero spezzato dalla

furia della tempesta; il canneto dorato che ondeggia al vento,

e poi azzurri e verdi digradanti all’infinito, che disegnano

colline, montagne, cielo e nuvole. L’unica presenza umana è

quella di alcuni personaggi in

barca,

appena

riconoscibili

dietro

l’albero

in

primo

piano. Qui Annibale Carracci

inverte i ruoli: l’Uomo si fa

piccolo di fronte alla potenza

della Natura che, secondo i

precetti della Controriforma, è

manifestazione concreta della

luce divina. E quindi la Natura

diventa protagonista indiscussa

dell’opera. Annibale Carracci fa

nascere la pittura di paesaggio.

L’attenzione per la Natura

si spinge poi ai confini della

ricerca scientifica nella Fuga

in Egitto di Adam Elsheimer,

artista tedesco attivo nella

Roma barocca. Nell’opera del

1609, conservata alla Alte

Pinakothek di Monaco, si capisce che il vero interesse del pittore

è per l’esplorazione del cielo stellato, che non a caso occupa

gran parte del quadro. E così, per mascherare questa attenzione

per l’astronomia, che poteva risultare sospetta agli inquisitori

del Sant’Uffizio, Elsheimer prende in prestito il soggetto della

Sacra Famiglia in fuga da Erode dipingendo i protagonisti

piccoli e appena visibili in basso, illuminati dalla debole luce di

una torcia.Per la prima volta il vero soggetto dell’opera è la volta

celeste, puntellata di costellazioni e pianeti, osservata da vicino

grazie al telescopio, che proprio in quei mesi Galileo Galilei

aveva presentato destando grande clamore. Se Annibale Carracci

divide in due la tela usando il tronco di un albero, Elsheimer

adopera la Via Lattea per ripartire il quadro in diagonale e

is clear after all this chasing after things: Nature is dominated by

Man, who governs the trees in the forest and hunts the animals

living there. The artist’s solution of placing the prey at the

centre is a symbolic representation that defines the role of Man

in Creation. At the same time the perspective leads to infinity,

to God. More than a century would go by before another artist

began to view Nature for what it really is and consider it the

primary subject of a work of art. This turning point came with

Annibale Carracci, who painted River Landscape, now held in

the National Gallery of Art in Washington, in 1590. In this

painting the Bologna artist feigning work en plein air, hides

in the woods and contemplating the landscape, the trunk of a

large oak tree positioned in front of his gaze. All is real: the tree

broken by the fury of a storm; the golden reed bank swaying in the

wind; the blues and greens fading to infinity, delineating hills,

mountains, sky, and clouds. The only human presence is that

of some figures in a boat, barely discernible behind the tree in

the foreground. In this painting Annibale Carracci has inverted

the roles. Man is dwarfed by the

power of Nature which, based on

Counter-Reformation precepts,

is a concrete manifestation

of the divine light. Nature

has become the undisputed

protagonist in this work of art.

Annibale Carracci gave birth

to the painting of landscape.

The

interest

in

Nature

is

pushed almost to the limit of

scientific research in The Flight

into Egypt, a work by Adam

Elsheimer, a German artist

active in baroque Rome. In this

painting of 1609, now housed in

Munich’s Alte Pinakothek, it is

clear the painter’s real interest

lies in exploring the starry sky

and it is no coincidence the sky

takes up almost all of the painting. Disguising his interest in

astronomy, which might have caused suspicion in Holy Office

inquisitors, Elsheimer borrowed the subject of the Holy Family

fleeing from Herod, painting the tiny protagonists at the bottom

of the canvas, lit up by the faint light of a burning torch and

barely visible.For the first time the real subject of a work of art

is the celestial vault, scattered with planets and constellations

and observed closely through a telescope, an instrument Galileo

Galilei had presented to great acclaim in those same months.

While Annibale Carracci divided his canvas into two using the

trunk of a tree, Elsheimer has used the Milky Way to divide

the painting diagonally, drawing the viewer’s attention to the

reality of the Unknown, contemplation of the Universe and

“Marat (Sebastião)”.

Nella pagina precedente una delle opere

di Vik Muniz della serie “Pictures of

Garbage”, 2008.

Previous page, one of the works by

Vik Muniz from the series “Pictures of

Garbage”, 2008.

Edra Magazine n°5

26

27

FOCUS