Giampaolo Grassi.

Giornalista parlamentare dell’Ansa. Prima di occuparsi di politica, ha seguito la cronaca giudiziaria a Firenze e quella finanziaria a Milano. Ha raccolto storia, ricordi e pensieri

di Francesco Binfaré in un volume pubblicato dalla casa editrice Mandragora.

A parliamentary journalist for ANSA news agency, before writing about politics Grassi covered judicial news in Florence and financial news in Milan. In his book on Francesco

Binfaré, published by Mandragora, he gathers the artist and designer’s story, thinking and memories.

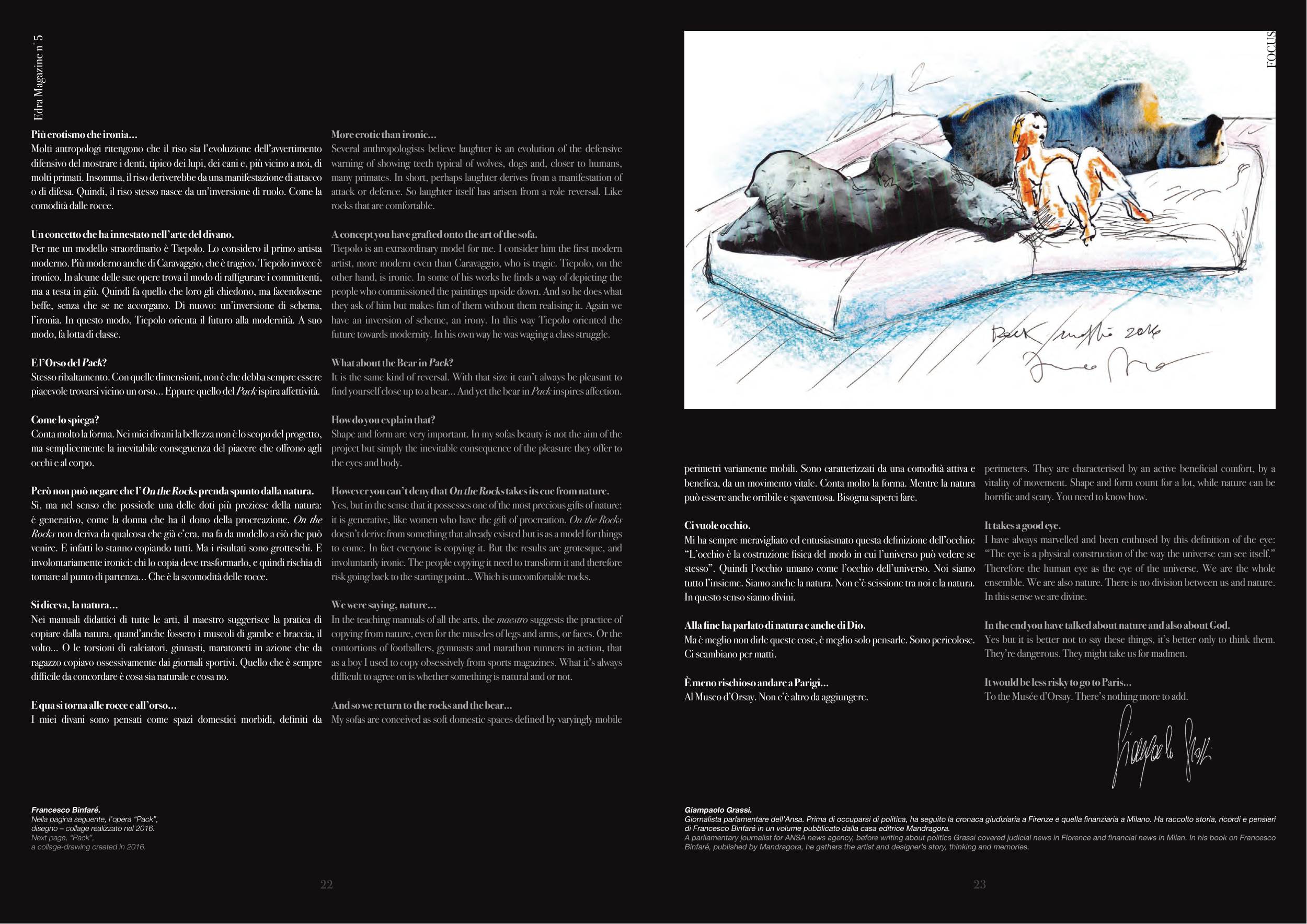

Francesco Binfaré.

Nella pagina seguente, l’opera “Pack”,

disegno – collage realizzato nel 2016.

Next page, “Pack”,

a collage-drawing created in 2016.

Più erotismo che ironia…

Molti antropologi ritengono che il riso sia l’evoluzione dell’avvertimento

difensivo del mostrare i denti, tipico dei lupi, dei cani e, più vicino a noi, di

molti primati. Insomma, il riso deriverebbe da una manifestazione di attacco

o di difesa. Quindi, il riso stesso nasce da un’inversione di ruolo. Come la

comodità dalle rocce.

Un concetto che ha innestato nell’arte del divano.

Per me un modello straordinario è Tiepolo. Lo considero il primo artista

moderno. Più moderno anche di Caravaggio, che è tragico. Tiepolo invece è

ironico. In alcune delle sue opere trova il modo di raffigurare i committenti,

ma a testa in giù. Quindi fa quello che loro gli chiedono, ma facendosene

beffe, senza che se ne accorgano. Di nuovo: un’inversione di schema,

l’ironia. In questo modo, Tiepolo orienta il futuro alla modernità. A suo

modo, fa lotta di classe.

E l’Orso del Pack?

Stesso ribaltamento. Con quelle dimensioni, non è che debba sempre essere

piacevole trovarsi vicino un orso... Eppure quello del Pack ispira affettività.

Come lo spiega?

Conta molto la forma. Nei miei divani la bellezza non è lo scopo del progetto,

ma semplicemente la inevitabile conseguenza del piacere che offrono agli

occhi e al corpo.

Però non può negare che l’On the Rocks prenda spunto dalla natura.

Sì, ma nel senso che possiede una delle doti più preziose della natura:

è generativo, come la donna che ha il dono della procreazione. On the

Rocks non deriva da qualcosa che già c’era, ma fa da modello a ciò che può

venire. E infatti lo stanno copiando tutti. Ma i risultati sono grotteschi. E

involontariamente ironici: chi lo copia deve trasformarlo, e quindi rischia di

tornare al punto di partenza… Che è la scomodità delle rocce.

Si diceva, la natura…

Nei manuali didattici di tutte le arti, il maestro suggerisce la pratica di

copiare dalla natura, quand’anche fossero i muscoli di gambe e braccia, il

volto... O le torsioni di calciatori, ginnasti, maratoneti in azione che da

ragazzo copiavo ossessivamente dai giornali sportivi. Quello che è sempre

difficile da concordare è cosa sia naturale e cosa no.

E qua si torna alle rocce e all’orso…

I miei divani sono pensati come spazi domestici morbidi, definiti da

perimetri variamente mobili. Sono caratterizzati da una comodità attiva e

benefica, da un movimento vitale. Conta molto la forma. Mentre la natura

può essere anche orribile e spaventosa. Bisogna saperci fare.

Ci vuole occhio.

Mi ha sempre meravigliato ed entusiasmato questa definizione dell’occhio:

“L’occhio è la costruzione fisica del modo in cui l’universo può vedere se

stesso”. Quindi l’occhio umano come l’occhio dell’universo. Noi siamo

tutto l’insieme. Siamo anche la natura. Non c’è scissione tra noi e la natura.

In questo senso siamo divini.

Alla fine ha parlato di natura e anche di Dio.

Ma è meglio non dirle queste cose, è meglio solo pensarle. Sono pericolose.

Ci scambiano per matti.

È meno rischioso andare a Parigi...

Al Museo d’Orsay. Non c’è altro da aggiungere.

More erotic than ironic…

Several anthropologists believe laughter is an evolution of the defensive

warning of showing teeth typical of wolves, dogs and, closer to humans,

many primates. In short, perhaps laughter derives from a manifestation of

attack or defence. So laughter itself has arisen from a role reversal. Like

rocks that are comfortable.

A concept you have grafted onto the art of the sofa.

Tiepolo is an extraordinary model for me. I consider him the first modern

artist, more modern even than Caravaggio, who is tragic. Tiepolo, on the

other hand, is ironic. In some of his works he finds a way of depicting the

people who commissioned the paintings upside down. And so he does what

they ask of him but makes fun of them without them realising it. Again we

have an inversion of scheme, an irony. In this way Tiepolo oriented the

future towards modernity. In his own way he was waging a class struggle.

What about the Bear in Pack?

It is the same kind of reversal. With that size it can’t always be pleasant to

find yourself close up to a bear... And yet the bear in Pack inspires affection.

How do you explain that?

Shape and form are very important. In my sofas beauty is not the aim of the

project but simply the inevitable consequence of the pleasure they offer to

the eyes and body.

However you can’t deny that On the Rocks takes its cue from nature.

Yes, but in the sense that it possesses one of the most precious gifts of nature:

it is generative, like women who have the gift of procreation. On the Rocks

doesn’t derive from something that already existed but is as a model for things

to come. In fact everyone is copying it. But the results are grotesque, and

involuntarily ironic. The people copying it need to transform it and therefore

risk going back to the starting point... Which is uncomfortable rocks.

We were saying, nature…

In the teaching manuals of all the arts, the maestro suggests the practice of

copying from nature, even for the muscles of legs and arms, or faces. Or the

contortions of footballers, gymnasts and marathon runners in action, that

as a boy I used to copy obsessively from sports magazines. What it’s always

difficult to agree on is whether something is natural and or not.

And so we return to the rocks and the bear...

My sofas are conceived as soft domestic spaces defined by varyingly mobile

perimeters. They are characterised by an active beneficial comfort, by a

vitality of movement. Shape and form count for a lot, while nature can be

horrific and scary. You need to know how.

It takes a good eye.

I have always marvelled and been enthused by this definition of the eye:

“The eye is a physical construction of the way the universe can see itself.”

Therefore the human eye as the eye of the universe. We are the whole

ensemble. We are also nature. There is no division between us and nature.

In this sense we are divine.

In the end you have talked about nature and also about God.

Yes but it is better not to say these things, it’s better only to think them.

They’re dangerous. They might take us for madmen.

It would be less risky to go to Paris...

To the Musée d’Orsay. There’s nothing more to add.

Edra Magazine n°5

22

23

FOCUS