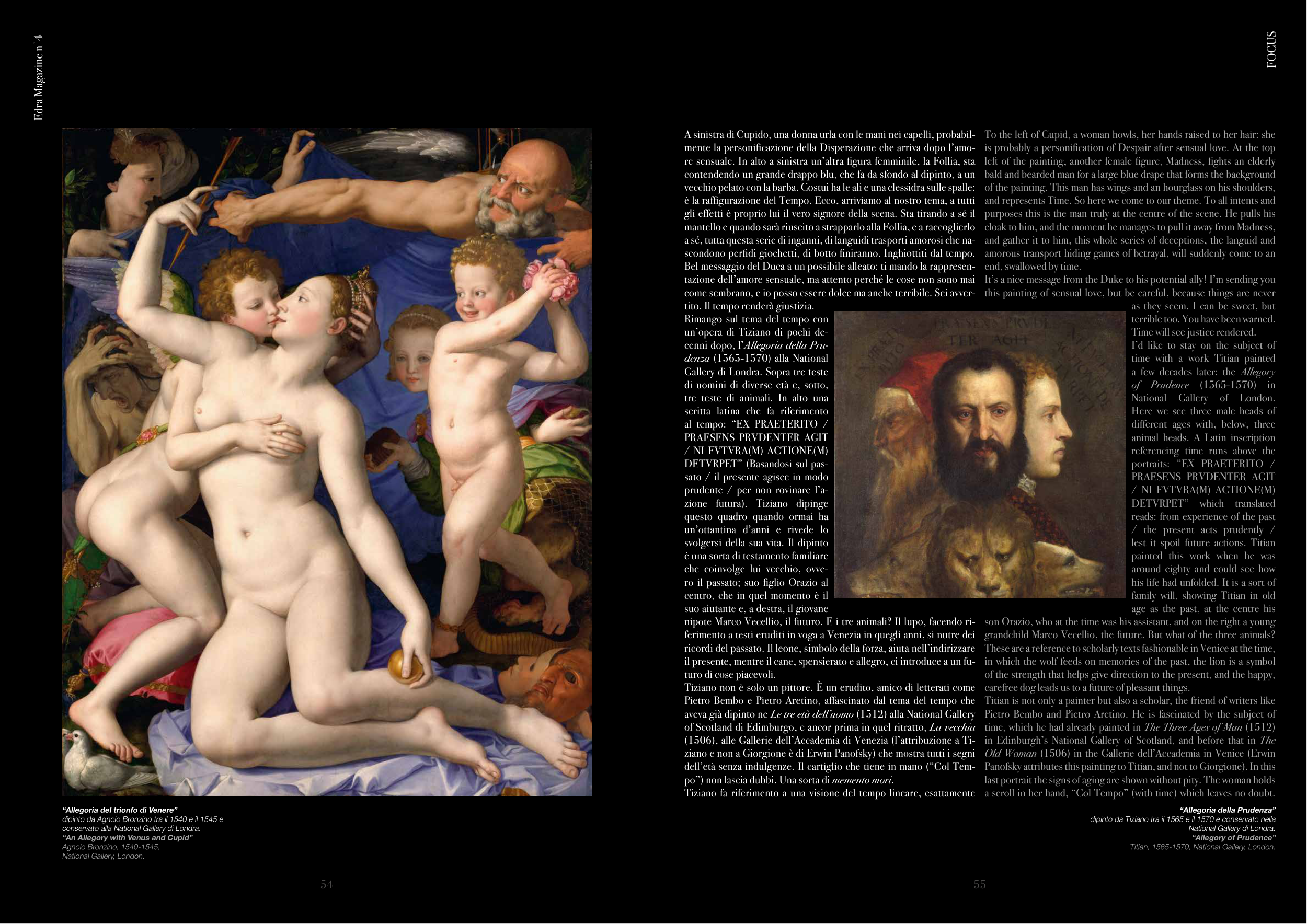

“Allegoria della Prudenza”

dipinto da Tiziano tra il 1565 e il 1570 e conservato nella

National Gallery di Londra.

“Allegory of Prudence”

Titian, 1565-1570, National Gallery, London.

A sinistra di Cupido, una donna urla con le mani nei capelli, probabil-

mente la personificazione della Disperazione che arriva dopo l’amo-

re sensuale. In alto a sinistra un’altra figura femminile, la Follia, sta

contendendo un grande drappo blu, che fa da sfondo al dipinto, a un

vecchio pelato con la barba. Costui ha le ali e una clessidra sulle spalle:

è la raffigurazione del Tempo. Ecco, arriviamo al nostro tema, a tutti

gli effetti è proprio lui il vero signore della scena. Sta tirando a sé il

mantello e quando sarà riuscito a strapparlo alla Follia, e a raccoglierlo

a sé, tutta questa serie di inganni, di languidi trasporti amorosi che na-

scondono perfidi giochetti, di botto finiranno. Inghiottiti dal tempo.

Bel messaggio del Duca a un possibile alleato: ti mando la rappresen-

tazione dell’amore sensuale, ma attento perché le cose non sono mai

come sembrano, e io posso essere dolce ma anche terribile. Sei avver-

tito. Il tempo renderà giustizia.

Rimango sul tema del tempo con

un’opera di Tiziano di pochi de-

cenni dopo, l’Allegoria della Pru-

denza (1565-1570) alla National

Gallery di Londra. Sopra tre teste

di uomini di diverse età e, sotto,

tre teste di animali. In alto una

scritta latina che fa riferimento

al tempo: “EX PRAETERITO /

PRAESENS PRVDENTER AGIT

/ NI FVTVRA(M) ACTIONE(M)

DETVRPET” (Basandosi sul pas-

sato / il presente agisce in modo

prudente / per non rovinare l’a-

zione futura). Tiziano dipinge

questo quadro quando ormai ha

un’ottantina d’anni e rivede lo

svolgersi della sua vita. Il dipinto

è una sorta di testamento familiare

che coinvolge lui vecchio, ovve-

ro il passato; suo figlio Orazio al

centro, che in quel momento è il

suo aiutante e, a destra, il giovane

nipote Marco Vecellio, il futuro. E i tre animali? Il lupo, facendo ri-

ferimento a testi eruditi in voga a Venezia in quegli anni, si nutre dei

ricordi del passato. Il leone, simbolo della forza, aiuta nell’indirizzare

il presente, mentre il cane, spensierato e allegro, ci introduce a un fu-

turo di cose piacevoli.

Tiziano non è solo un pittore. È un erudito, amico di letterati come

Pietro Bembo e Pietro Aretino, affascinato dal tema del tempo che

aveva già dipinto ne Le tre età dell’uomo (1512) alla National Gallery

of Scotland di Edimburgo, e ancor prima in quel ritratto, La vecchia

(1506), alle Gallerie dell’Accademia di Venezia (l’attribuzione a Ti-

ziano e non a Giorgione è di Erwin Panofsky) che mostra tutti i segni

dell’età senza indulgenze. Il cartiglio che tiene in mano (“Col Tem-

po”) non lascia dubbi. Una sorta di memento mori.

Tiziano fa riferimento a una visione del tempo lineare, esattamente

“Allegoria del trionfo di Venere”

dipinto da Agnolo Bronzino tra il 1540 e il 1545 e

conservato alla National Gallery di Londra.

“An Allegory with Venus and Cupid”

Agnolo Bronzino, 1540-1545,

National Gallery, London.

To the left of Cupid, a woman howls, her hands raised to her hair: she

is probably a personification of Despair after sensual love. At the top

left of the painting, another female figure, Madness, fights an elderly

bald and bearded man for a large blue drape that forms the background

of the painting. This man has wings and an hourglass on his shoulders,

and represents Time. So here we come to our theme. To all intents and

purposes this is the man truly at the centre of the scene. He pulls his

cloak to him, and the moment he manages to pull it away from Madness,

and gather it to him, this whole series of deceptions, the languid and

amorous transport hiding games of betrayal, will suddenly come to an

end, swallowed by time.

It’s a nice message from the Duke to his potential ally! I’m sending you

this painting of sensual love, but be careful, because things are never

as they seem. I can be sweet, but

terrible too. You have been warned.

Time will see justice rendered.

I’d like to stay on the subject of

time with a work Titian painted

a few decades later: the Allegory

of Prudence (1565-1570) in

National

Gallery

of

London.

Here we see three male heads of

different ages with, below, three

animal heads. A Latin inscription

referencing time runs above the

portraits: “EX PRAETERITO /

PRAESENS PRVDENTER AGIT

/ NI FVTVRA(M) ACTIONE(M)

DETVRPET”

which

translated

reads: from experience of the past

/ the present acts prudently /

lest it spoil future actions. Titian

painted this work when he was

around eighty and could see how

his life had unfolded. It is a sort of

family will, showing Titian in old

age as the past, at the centre his

son Orazio, who at the time was his assistant, and on the right a young

grandchild Marco Vecellio, the future. But what of the three animals?

These are a reference to scholarly texts fashionable in Venice at the time,

in which the wolf feeds on memories of the past, the lion is a symbol

of the strength that helps give direction to the present, and the happy,

carefree dog leads us to a future of pleasant things.

Titian is not only a painter but also a scholar, the friend of writers like

Pietro Bembo and Pietro Aretino. He is fascinated by the subject of

time, which he had already painted in The Three Ages of Man (1512)

in Edinburgh’s National Gallery of Scotland, and before that in The

Old Woman (1506) in the Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice (Erwin

Panofsky attributes this painting to Titian, and not to Giorgione). In this

last portrait the signs of aging are shown without pity. The woman holds

a scroll in her hand, “Col Tempo” (with time) which leaves no doubt.

Edra Magazine n°4

54

55

FOCUS