62

63

gli arredi. Una sorta di metaverso al contrario, costruito nella

realtà invece che in un mondo immaginario. Questa tendenza

di fatto tradisce lo spirito del progetto di arredo, che – come

insegna Andrea Branzi – nasce con l’uomo, come risposta

ai suoi bisogni. Basti pensare che la maggior parte degli

oggetti che usiamo da tempo immemorabile non hanno una

paternità accertata. Sappiamo chi ha inventato la forchetta?

Il pettine? La sedia? No. E l’elenco

è sterminato. Achille Castiglioni

amava collezionare oggetti di

design anonimo che mostrava con

orgoglio ai suoi studenti, parlava

più di questi che dei suoi.

Di certo, quando la funzionalità

del segno supera quella dell’uso,

quando non si lavora più con

attenzione

quasi

spasmodica

al prodotto ma ancor prima

agli elementi comunicativi che

esprime, torna utile l’avvertimento

di cinquant’anni fa del fi losofo e

critico d’arte Dino Formaggio,

che scriveva che “l’arte è tutto ciò

che gli uomini chiamano arte”.

Così facendo metteva in guardia

dal rischio che, perdendo la

sua piena funzionalità estetica,

l’arte si staccasse anche dalla

vita delle persone e dalla società.

Parafrasando

questo

assunto,

viene da chiedersi a questo punto:

cosa è allora tutto ciò gli uomini

chiamano design?

In conclusione, lavorando su un piano di riconoscimento

inverso, Edra sa bene cosa signifi ca progetto di arredo. E

nella sua scelta di campo sembra piuttosto voler recuperare

quel clima rinascimentale di totale armonia tra arte e alto

artigianato in cui è bello immergersi, guardando al tempo

lungo della storia.

Pierluigi Masini

Giornalista professionista, laureato in Lettere con indirizzo Storia dell’Arte, due master in Marketing e Comunicazione. Insegna Storia del Design alla Raffl es

Milano, Interior Design and Sustainability alla Yacademy e Fenomenologia delle arti contemporanee alla LABA di Brescia. Ha scritto un libro su Gabriella Crespi.

Professional journalist, with a degree in Literature and specialization in History of Art, two masters‘ degrees in Marketing and Communication. He teaches

History of Design at Raffl es Milan, Interior Design and Sustainability at the Yacademy and Phenomenology of Contemporary Arts at LABA in Brescia. He wrote

a book about Gabriella Crespi.

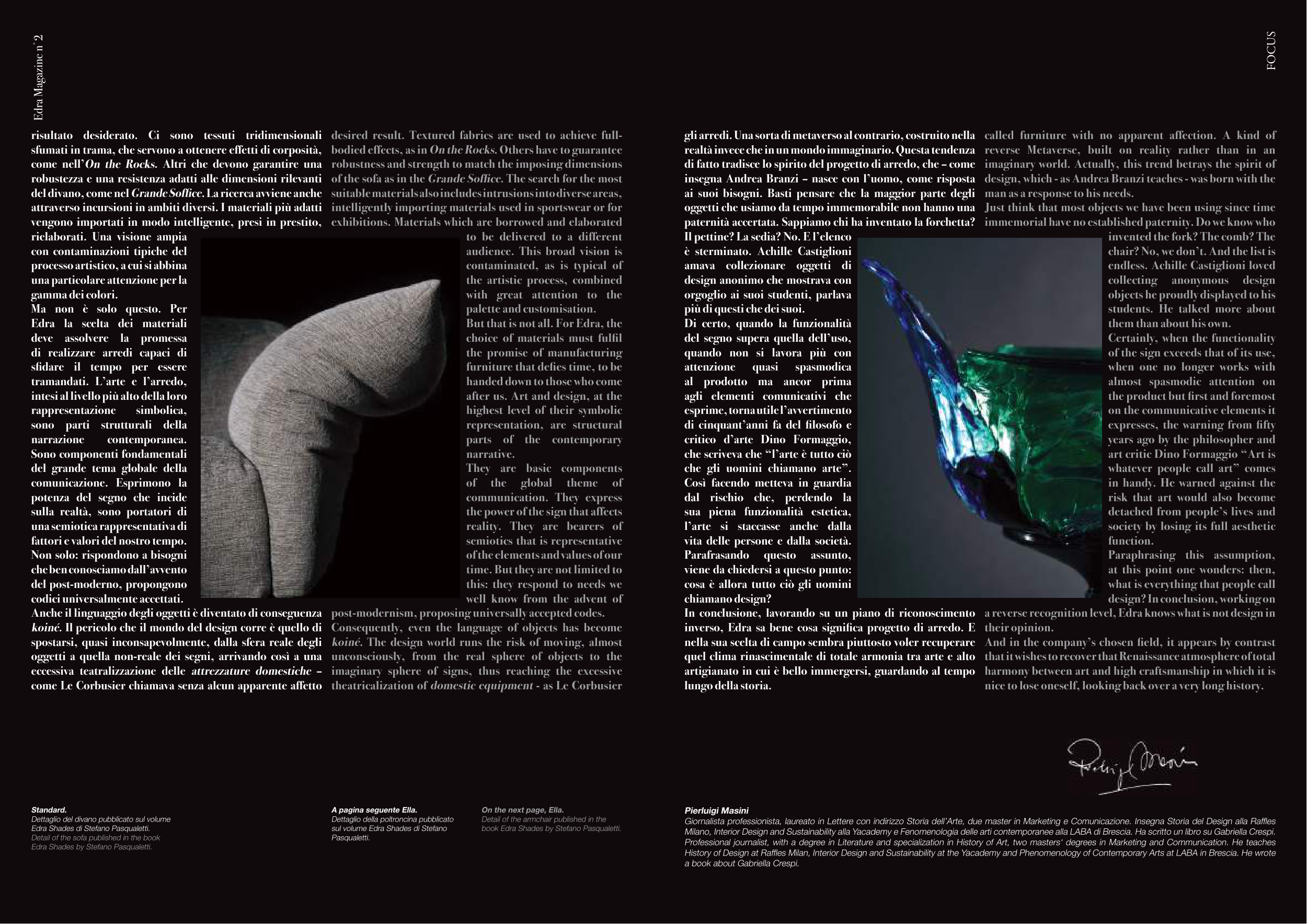

Standard.

Dettaglio del divano pubblicato sul volume

Edra Shades di Stefano Pasqualetti.

Detail of the sofa published in the book

Edra Shades by Stefano Pasqualetti.

A pagina seguente Ella.

Dettaglio della poltroncina pubblicato

sul volume Edra Shades di Stefano

Pasqualetti.

On the next page, Ella.

Detail of the armchair published in the

book Edra Shades by Stefano Pasqualetti.

risultato desiderato. Ci sono tessuti tridimensionali

sfumati in trama, che servono a ottenere effetti di corposità,

come nell’On the Rocks. Altri che devono garantire una

robustezza e una resistenza adatti alle dimensioni rilevanti

del divano, come nel Grande Soffi ce. La ricerca avviene anche

attraverso incursioni in ambiti diversi. I materiali più adatti

vengono importati in modo intelligente, presi in prestito,

rielaborati. Una visione ampia

con contaminazioni tipiche del

processo artistico, a cui si abbina

una particolare attenzione per la

gamma dei colori.

Ma non è solo questo. Per

Edra la scelta dei materiali

deve

assolvere

la

promessa

di realizzare arredi capaci di

sfi dare il tempo per essere

tramandati. L’arte e l’arredo,

intesi al livello più alto della loro

rappresentazione

simbolica,

sono parti strutturali della

narrazione

contemporanea.

Sono componenti fondamentali

del grande tema globale della

comunicazione. Esprimono la

potenza del segno che incide

sulla realtà, sono portatori di

una semiotica rappresentativa di

fattori e valori del nostro tempo.

Non solo: rispondono a bisogni

che ben conosciamo dall’avvento

del post-moderno, propongono

codici universalmente accettati.

Anche il linguaggio degli oggetti è diventato di conseguenza

koiné. Il pericolo che il mondo del design corre è quello di

spostarsi, quasi inconsapevolmente, dalla sfera reale degli

oggetti a quella non-reale dei segni, arrivando così a una

eccessiva teatralizzazione delle attrezzature domestiche –

come Le Corbusier chiamava senza alcun apparente affetto

desired result. Textured fabrics are used to achieve full-

bodied effects, as in On the Rocks. Others have to guarantee

robustness and strength to match the imposing dimensions

of the sofa as in the Grande Soffi ce. The search for the most

suitable materials also includes intrusions into diverse areas,

intelligently importing materials used in sportswear or for

exhibitions. Materials which are borrowed and elaborated

to be delivered to a different

audience. This broad vision is

contaminated, as is typical of

the artistic process, combined

with great attention to the

palette and customisation.

But that is not all. For Edra, the

choice of materials must fulfi l

the promise of manufacturing

furniture that defi es time, to be

handed down to those who come

after us. Art and design, at the

highest level of their symbolic

representation, are structural

parts

of

the

contemporary

narrative.

They are basic components

of

the

global

theme

of

communication. They express

the power of the sign that affects

reality. They are bearers of

semiotics that is representative

of the elements and values of our

time. But they are not limited to

this: they respond to needs we

well know from the advent of

post-modernism, proposing universally accepted codes.

Consequently, even the language of objects has become

koiné. The design world runs the risk of moving, almost

unconsciously, from the real sphere of objects to the

imaginary sphere of signs, thus reaching the excessive

theatricalization of domestic equipment - as Le Corbusier

called furniture with no apparent affection. A kind of

reverse Metaverse, built on reality rather than in an

imaginary world. Actually, this trend betrays the spirit of

design, which - as Andrea Branzi teaches - was born with the

man as a response to his needs.

Just think that most objects we have been using since time

immemorial have no established paternity. Do we know who

invented the fork? The comb? The

chair? No, we don’t. And the list is

endless. Achille Castiglioni loved

collecting

anonymous

design

objects he proudly displayed to his

students. He talked more about

them than about his own.

Certainly, when the functionality

of the sign exceeds that of its use,

when one no longer works with

almost spasmodic attention on

the product but fi rst and foremost

on the communicative elements it

expresses, the warning from fi fty

years ago by the philosopher and

art critic Dino Formaggio “Art is

whatever people call art” comes

in handy. He warned against the

risk that art would also become

detached from people’s lives and

society by losing its full aesthetic

function.

Paraphrasing this assumption,

at this point one wonders: then,

what is everything that people call

design? In conclusion, working on

a reverse recognition level, Edra knows what is not design in

their opinion.

And in the company’s chosen fi eld, it appears by contrast

that it wishes to recover that Renaissance atmosphere of total

harmony between art and high craftsmanship in which it is

nice to lose oneself, looking back over a very long history.

Edra Magazine n°2

FOCUS