26

27

palio e la doverosa partecipazione di tutte le Autorità

cittadine. In seguito, specialmente a partire dal

Seicento, Forlì divenne città mariana, col prevalere

del patrocinio della Madonna del fuoco. Si sa che la

mamma è sempre la mamma, ma, in questo caso, a

detrimento del culto del Santo Protovescovo incise

anche il contrasto tra l’Abate e il Vescovo diocesano.

In tempi recenti, la memoria liturgica del Santo è

stata trasferita al 26 ottobre, giorno in cui agli inizi del

XVII secolo le reliquie furono collocate nella cappella

Mercuriali, dove tuttora si trovano, dopo essere

state deposte, due anni fa, in un’urna marmorea

commissionata a tal fine. Desidero ricordare, di

sfuggita, che la ricognizione canonico-scientifica

delle suddette reliquie, voluta tre anni or sono, ha

dato esiti che confermano in modo sorprendente la

tradizione circa la provenienza di Mercuriale dalla

lontana Armenia. E le analisi non sono ancora finite.

Tutto questo porrebbe la città di Forlì in un orizzonte

molto più ampio, collegandola al più antico regno

cristiano del mondo, quello dell’Armenia appunto.

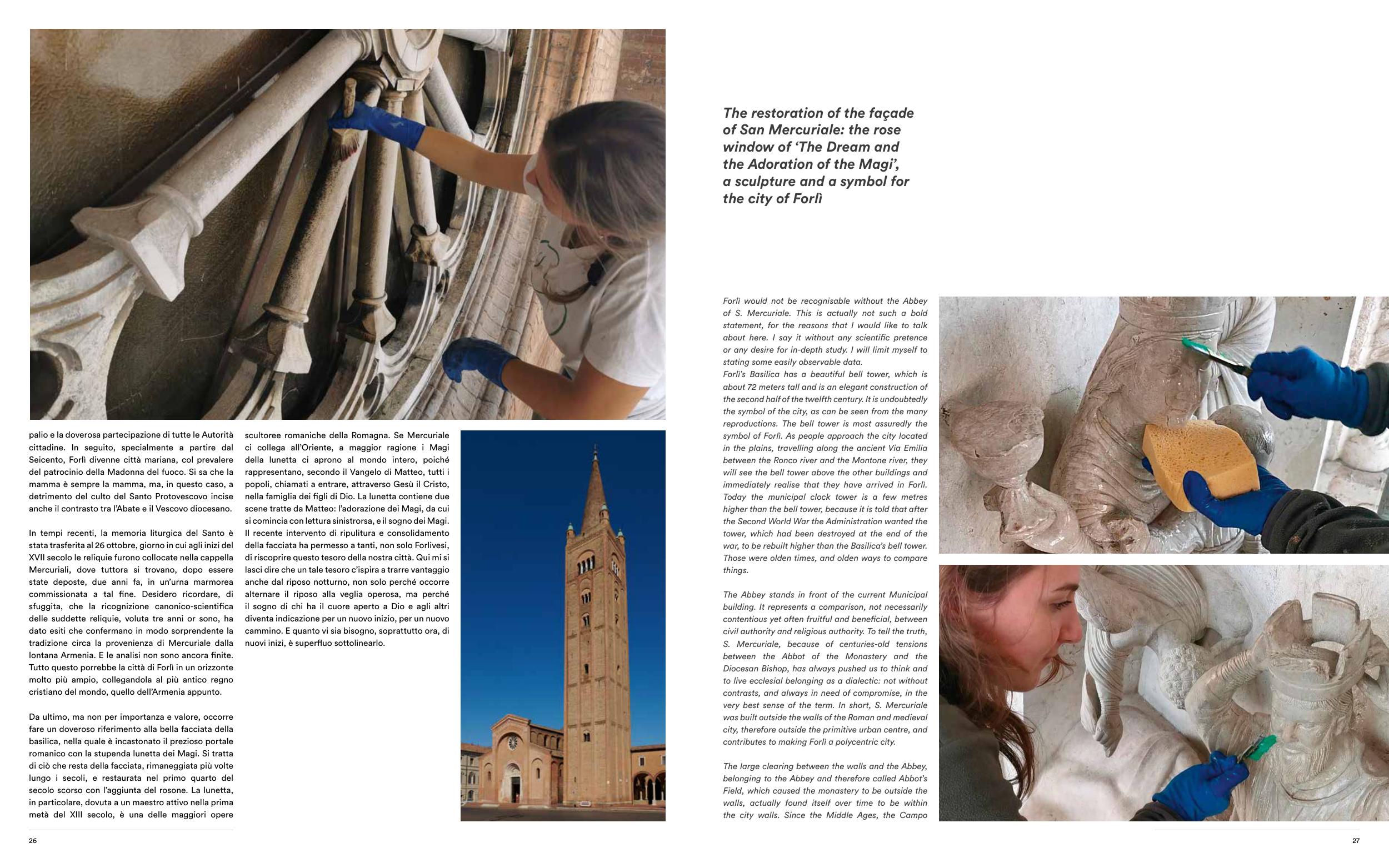

Da ultimo, ma non per importanza e valore, occorre

fare un doveroso riferimento alla bella facciata della

basilica, nella quale è incastonato il prezioso portale

romanico con la stupenda lunetta dei Magi. Si tratta

di ciò che resta della facciata, rimaneggiata più volte

lungo i secoli, e restaurata nel primo quarto del

secolo scorso con l’aggiunta del rosone. La lunetta,

in particolare, dovuta a un maestro attivo nella prima

metà del XIII secolo, è una delle maggiori opere

scultoree romaniche della Romagna. Se Mercuriale

ci collega all’Oriente, a maggior ragione i Magi

della lunetta ci aprono al mondo intero, poiché

rappresentano, secondo il Vangelo di Matteo, tutti i

popoli, chiamati a entrare, attraverso Gesù il Cristo,

nella famiglia dei figli di Dio. La lunetta contiene due

scene tratte da Matteo: l’adorazione dei Magi, da cui

si comincia con lettura sinistrorsa, e il sogno dei Magi.

Il recente intervento di ripulitura e consolidamento

della facciata ha permesso a tanti, non solo Forlivesi,

di riscoprire questo tesoro della nostra città. Qui mi si

lasci dire che un tale tesoro c’ispira a trarre vantaggio

anche dal riposo notturno, non solo perché occorre

alternare il riposo alla veglia operosa, ma perché

il sogno di chi ha il cuore aperto a Dio e agli altri

diventa indicazione per un nuovo inizio, per un nuovo

cammino. E quanto vi sia bisogno, soprattutto ora, di

nuovi inizi, è superfluo sottolinearlo.

The restoration of the façade

of San Mercuriale: the rose

window of ‘The Dream and

the Adoration of the Magi’,

a sculpture and a symbol for

the city of Forlì

Forlì would not be recognisable without the Abbey

of S. Mercuriale. This is actually not such a bold

statement, for the reasons that I would like to talk

about here. I say it without any scientific pretence

or any desire for in-depth study. I will limit myself to

stating some easily observable data.

Forlì’s Basilica has a beautiful bell tower, which is

about 72 meters tall and is an elegant construction of

the second half of the twelfth century. It is undoubtedly

the symbol of the city, as can be seen from the many

reproductions. The bell tower is most assuredly the

symbol of Forlì. As people approach the city located

in the plains, travelling along the ancient Via Emilia

between the Ronco river and the Montone river, they

will see the bell tower above the other buildings and

immediately realise that they have arrived in Forlì.

Today the municipal clock tower is a few metres

higher than the bell tower, because it is told that after

the Second World War the Administration wanted the

tower, which had been destroyed at the end of the

war, to be rebuilt higher than the Basilica’s bell tower.

Those were olden times, and olden ways to compare

things.

The Abbey stands in front of the current Municipal

building. It represents a comparison, not necessarily

contentious yet often fruitful and beneficial, between

civil authority and religious authority. To tell the truth,

S. Mercuriale, because of centuries-old tensions

between the Abbot of the Monastery and the

Diocesan Bishop, has always pushed us to think and

to live ecclesial belonging as a dialectic: not without

contrasts, and always in need of compromise, in the

very best sense of the term. In short, S. Mercuriale

was built outside the walls of the Roman and medieval

city, therefore outside the primitive urban centre, and

contributes to making Forlì a polycentric city.

The large clearing between the walls and the Abbey,

belonging to the Abbey and therefore called Abbot’s

Field, which caused the monastery to be outside the

walls, actually found itself over time to be within

the city walls. Since the Middle Ages, the Campo