20

21

della

villeggiatura,

ormai

appannaggio

della

borghesia ricca e rampante e non più della consunta

nobiltà, si svolgeva nei lunghi mesi dell’estate. Solo

se si andava a passar le acque a Salsomaggiore,

Montecatini o a San Pellegrino era ideale l’autunno;

ci si dava invece appuntamento appena dopo Natale

o a Carnevale negli alberghi coi balconi e i timpani

in legno della Valle d’Aosta e delle Dolomiti per

dedicarsi ai bobsleighs, al pattinaggio, alle discese

vertiginose sugli sci e, per i più ardimentosi, al salto

dal trampolino.

La realizzazione dei nuovi Grand Hôtel presto

seguì un’impronta diversa, moderna e dallo stile

sobrio e, allo stesso tempo, prezioso. A contorno

della struttura vera e propria dedicata all’ospitalità

spesso nascevano ambienti deputati esclusivamente

allo svago, con invenzioni decorative tematiche,

e fantasiose, quasi a compensare il tono più

austero degli spazi istituzionali: nell’importante

complesso termale del Grand Hotel di Castrocaro

nasce addirittura un’architettura indipendente, il

Padiglione delle Feste con le soluzioni decorative

straordinariamente accattivanti di Tito Chini. Tutti

questi alberghi, vecchi e nuovi, si adeguarono con

prontezza alle esigenze di una clientela alquanto

sofisticata introducendo l’american bar arredato con

specchi e cristalli, mobili fin di metallo e pavimenti in

linoleum, il ping-pong in quella che era stata la sala

del biliardo, il garage per l’autovettura, emblema del

prestigio acquisito e del lusso esibito, e, al mare, la

spiaggia esclusiva con le cabine e gli ombrelloni dai

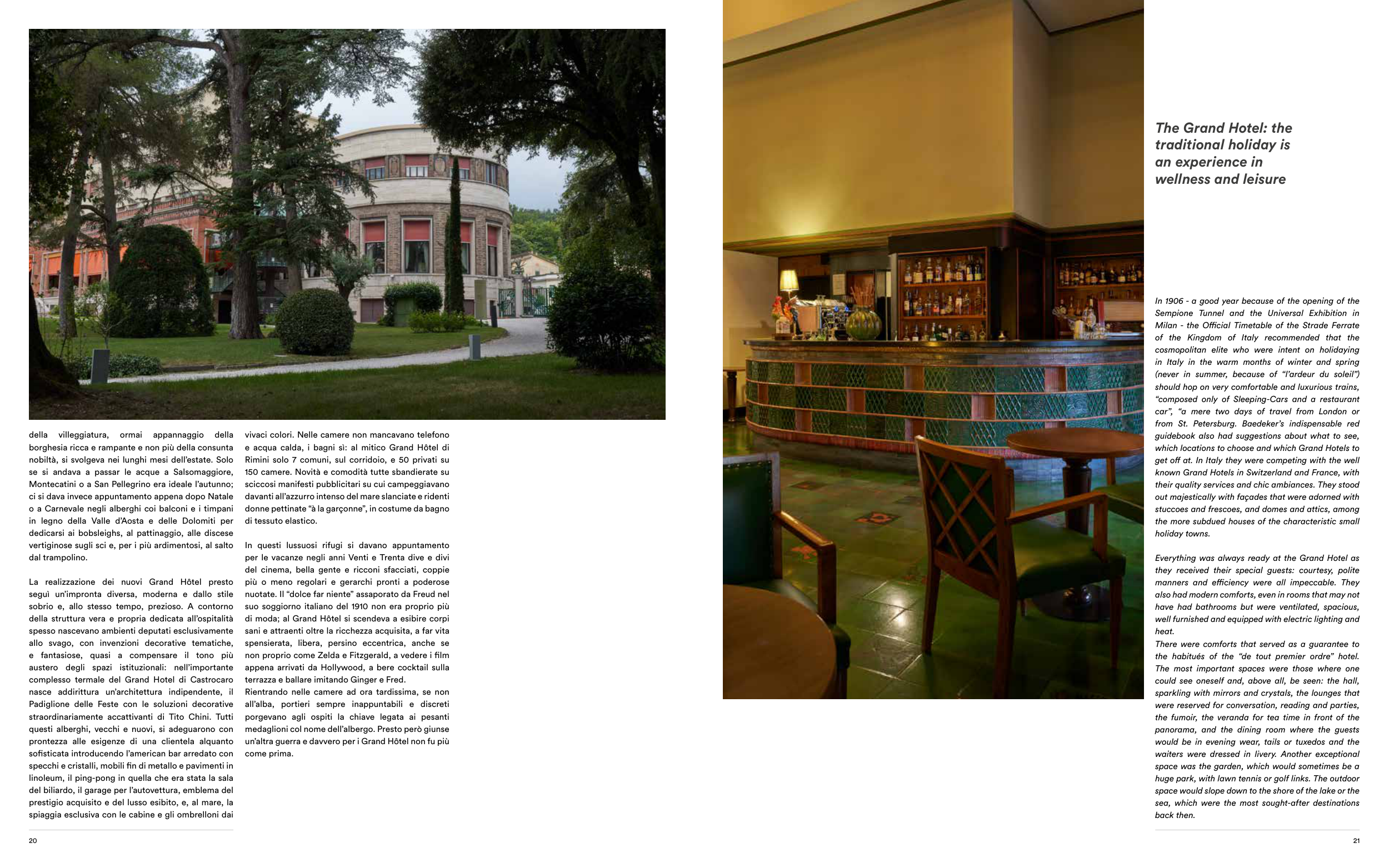

The Grand Hotel: the

traditional holiday is

an experience in

wellness and leisure

In 1906 - a good year because of the opening of the

Sempione Tunnel and the Universal Exhibition in

Milan - the Official Timetable of the Strade Ferrate

of the Kingdom of Italy recommended that the

cosmopolitan elite who were intent on holidaying

in Italy in the warm months of winter and spring

(never in summer, because of “l’ardeur du soleil”)

should hop on very comfortable and luxurious trains,

“composed only of Sleeping-Cars and a restaurant

car”, “a mere two days of travel from London or

from St. Petersburg. Baedeker’s indispensable red

guidebook also had suggestions about what to see,

which locations to choose and which Grand Hotels to

get off at. In Italy they were competing with the well

known Grand Hotels in Switzerland and France, with

their quality services and chic ambiances. They stood

out majestically with façades that were adorned with

stuccoes and frescoes, and domes and attics, among

the more subdued houses of the characteristic small

holiday towns.

Everything was always ready at the Grand Hotel as

they received their special guests: courtesy, polite

manners and efficiency were all impeccable. They

also had modern comforts, even in rooms that may not

have had bathrooms but were ventilated, spacious,

well furnished and equipped with electric lighting and

heat.

There were comforts that served as a guarantee to

the habitués of the “de tout premier ordre” hotel.

The most important spaces were those where one

could see oneself and, above all, be seen: the hall,

sparkling with mirrors and crystals, the lounges that

were reserved for conversation, reading and parties,

the fumoir, the veranda for tea time in front of the

panorama, and the dining room where the guests

would be in evening wear, tails or tuxedos and the

waiters were dressed in livery. Another exceptional

space was the garden, which would sometimes be a

huge park, with lawn tennis or golf links. The outdoor

space would slope down to the shore of the lake or the

sea, which were the most sought-after destinations

back then.

vivaci colori. Nelle camere non mancavano telefono

e acqua calda, i bagni sì: al mitico Grand Hôtel di

Rimini solo 7 comuni, sul corridoio, e 50 privati su

150 camere. Novità e comodità tutte sbandierate su

sciccosi manifesti pubblicitari su cui campeggiavano

davanti all’azzurro intenso del mare slanciate e ridenti

donne pettinate “à la garçonne”, in costume da bagno

di tessuto elastico.

In questi lussuosi rifugi si davano appuntamento

per le vacanze negli anni Venti e Trenta dive e divi

del cinema, bella gente e ricconi sfacciati, coppie

più o meno regolari e gerarchi pronti a poderose

nuotate. Il “dolce far niente” assaporato da Freud nel

suo soggiorno italiano del 1910 non era proprio più

di moda; al Grand Hôtel si scendeva a esibire corpi

sani e attraenti oltre la ricchezza acquisita, a far vita

spensierata, libera, persino eccentrica, anche se

non proprio come Zelda e Fitzgerald, a vedere i film

appena arrivati da Hollywood, a bere cocktail sulla

terrazza e ballare imitando Ginger e Fred.

Rientrando nelle camere ad ora tardissima, se non

all’alba, portieri sempre inappuntabili e discreti

porgevano agli ospiti la chiave legata ai pesanti

medaglioni col nome dell’albergo. Presto però giunse

un’altra guerra e davvero per i Grand Hôtel non fu più

come prima.