40 C 06

Innovation

Structures

3

Inflatables

Blow up! Ephemeral constructions

Las arquitecturas inflables o inflatoestructuras (como las llama el

arquitecto español Prada Poole) nos invitan a buscar la manera de

construir expresiones espaciales alternativas a los rígidos caminos

arquitectónicos que nos desilusionaban cuando éramos niños.

La construcción neumática actual tiene sus orígenes en las inves-

tigaciones desarrolladas durante la II Guerra Mundial. Los centros

de investigación militares construyeron hospitales, hangares y hasta

puentes inflables que resultaron muy eficaces por su facilidad de

transporte y velocidad de montaje. Se produjeron incluso tanques

inflables para utilizarlos como señuelos falsos ante los aviones de

reconocimiento enemigos. Tras la guerra, la experiencia adquirida se

aplicó a la industria para producir protecciones de radares y cubiertas

de barco, y también hangares móviles.

Posteriormente, se dio un segundo periodo de esplendor cuando los

materiales plásticos se pusieron de moda, en las décadas de 1960 y

1970. Los estudios de arquitectura contraculturales se apropiaron de

este lenguaje constructivo como herramienta subversiva y de crítica

a la arquitectura más académica, presentándola como la arquitectura

del cambio y lo efímero, como el hábitat del nómada contemporáneo.

Bajo esos preceptos se diseñaron propuestas como Corazón Amarillo

Vicenç Sarrablo & Nuria Prieto

Inflatable architectures (coined ‘inflatoestructuras’ in Spanish by ar-

chitect Prada Poole) invite us to look for the means, the way to build

space forms that provide alternatives to the strict architectural paths

that we found so disappointing when we were kids.

Current pneumatic architecture stems from the researches devel-

oped during World War II. Military research centers built hospitals,

hangars and even inflatable bridges that were very effective because

they were portable and quick to deploy. Even inflatable tanks were

built to confuse enemy surveillance aircrafts. After the war, all this

acquired experience was applied to the industry for the production of

radar protections and ship decks, as well as portable hangars.

Later on there was a second period of splendor when plastic materi-

als came back into fashion, in the 1960s and 1970s. Countercultural

architecture studios used this language it as a means to adopt a sub-

versive and critical stance against the most academic architecture,

presenting it as the architecture of change and the non-permanent,

as the habitat of the contemporary nomad. These precepts inspired

proposals like Yellow Heart by Hauss-Rucker-Co (1968), Parasites

by Missing Link Productions (1969), Dyodon by Jean Paul Jungman

(1967), Inflatables by Ant Farm (1970) or Instant City by Prada Poole.

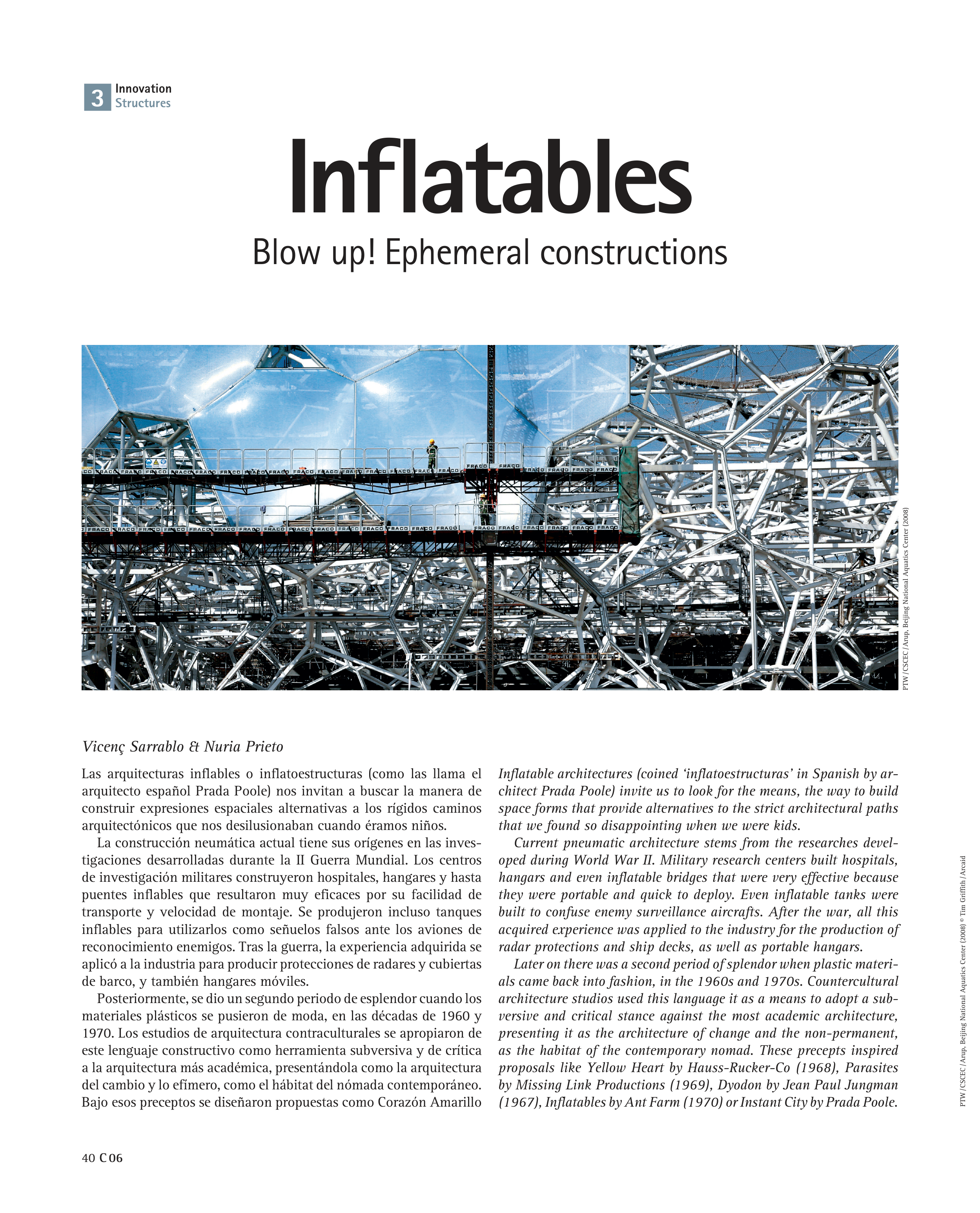

PTW / CSCEC / Arup, Beijing National Aquatics Center (2008) © Tim Griffith / Arcaid

PTW / CSCEC / Arup, Beijing National Aquatics Center (2008)