113

112

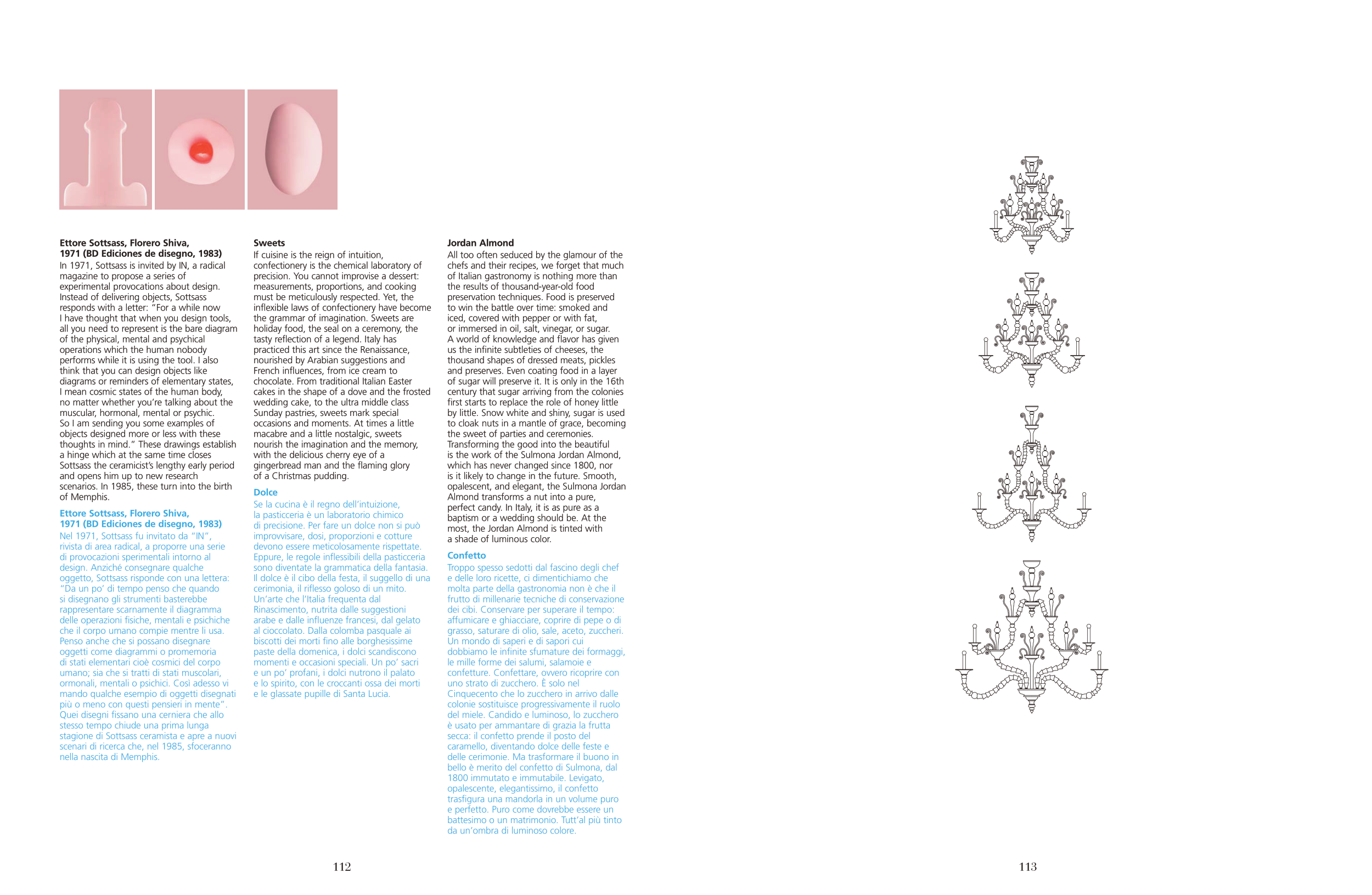

Ettore Sottsass, Florero Shiva,

1971 (BD Ediciones de disegno, 1983)

In 1971, Sottsass is invited by IN, a radical

magazine to propose a series of

experimental provocations about design.

Instead of delivering objects, Sottsass

responds with a letter: “For a while now

I have thought that when you design tools,

all you need to represent is the bare diagram

of the physical, mental and psychical

operations which the human nobody

performs while it is using the tool. I also

think that you can design objects like

diagrams or reminders of elementary states,

I mean cosmic states of the human body,

no matter whether you’re talking about the

muscular, hormonal, mental or psychic.

So I am sending you some examples of

objects designed more or less with these

thoughts in mind.” These drawings establish

a hinge which at the same time closes

Sottsass the ceramicist’s lengthy early period

and opens him up to new research

scenarios. In 1985, these turn into the birth

of Memphis.

Ettore Sottsass, Florero Shiva,

1971 (BD Ediciones de disegno, 1983)

Nel 1971, Sottsass fu invitato da “IN”,

rivista di area radical, a proporre una serie

di provocazioni sperimentali intorno al

design. Anziché consegnare qualche

oggetto, Sottsass risponde con una lettera:

“Da un po’ di tempo penso che quando

si disegnano gli strumenti basterebbe

rappresentare scarnamente il diagramma

delle operazioni fisiche, mentali e psichiche

che il corpo umano compie mentre li usa.

Penso anche che si possano disegnare

oggetti come diagrammi o promemoria

di stati elementari cioè cosmici del corpo

umano; sia che si tratti di stati muscolari,

ormonali, mentali o psichici. Così adesso vi

mando qualche esempio di oggetti disegnati

più o meno con questi pensieri in mente”.

Quei disegni fissano una cerniera che allo

stesso tempo chiude una prima lunga

stagione di Sottsass ceramista e apre a nuovi

scenari di ricerca che, nel 1985, sfoceranno

nella nascita di Memphis.

Sweets

If cuisine is the reign of intuition,

confectionery is the chemical laboratory of

precision. You cannot improvise a dessert:

measurements, proportions, and cooking

must be meticulously respected. Yet, the

inflexible laws of confectionery have become

the grammar of imagination. Sweets are

holiday food, the seal on a ceremony, the

tasty reflection of a legend. Italy has

practiced this art since the Renaissance,

nourished by Arabian suggestions and

French influences, from ice cream to

chocolate. From traditional Italian Easter

cakes in the shape of a dove and the frosted

wedding cake, to the ultra middle class

Sunday pastries, sweets mark special

occasions and moments. At times a little

macabre and a little nostalgic, sweets

nourish the imagination and the memory,

with the delicious cherry eye of a

gingerbread man and the flaming glory

of a Christmas pudding.

Dolce

Se la cucina è il regno dell’intuizione,

la pasticceria è un laboratorio chimico

di precisione. Per fare un dolce non si può

improvvisare, dosi, proporzioni e cotture

devono essere meticolosamente rispettate.

Eppure, le regole inflessibili della pasticceria

sono diventate la grammatica della fantasia.

Il dolce è il cibo della festa, il suggello di una

cerimonia, il riflesso goloso di un mito.

Un’arte che l’Italia frequenta dal

Rinascimento, nutrita dalle suggestioni

arabe e dalle influenze francesi, dal gelato

al cioccolato. Dalla colomba pasquale ai

biscotti dei morti fino alle borghesissime

paste della domenica, i dolci scandiscono

momenti e occasioni speciali. Un po’ sacri

e un po’ profani, i dolci nutrono il palato

e lo spirito, con le croccanti ossa dei morti

e le glassate pupille di Santa Lucia.

Jordan Almond

All too often seduced by the glamour of the

chefs and their recipes, we forget that much

of Italian gastronomy is nothing more than

the results of thousand-year-old food

preservation techniques. Food is preserved

to win the battle over time: smoked and

iced, covered with pepper or with fat,

or immersed in oil, salt, vinegar, or sugar.

A world of knowledge and flavor has given

us the infinite subtleties of cheeses, the

thousand shapes of dressed meats, pickles

and preserves. Even coating food in a layer

of sugar will preserve it. It is only in the 16th

century that sugar arriving from the colonies

first starts to replace the role of honey little

by little. Snow white and shiny, sugar is used

to cloak nuts in a mantle of grace, becoming

the sweet of parties and ceremonies.

Transforming the good into the beautiful

is the work of the Sulmona Jordan Almond,

which has never changed since 1800, nor

is it likely to change in the future. Smooth,

opalescent, and elegant, the Sulmona Jordan

Almond transforms a nut into a pure,

perfect candy. In Italy, it is as pure as a

baptism or a wedding should be. At the

most, the Jordan Almond is tinted with

a shade of luminous color.

Confetto

Troppo spesso sedotti dal fascino degli chef

e delle loro ricette, ci dimentichiamo che

molta parte della gastronomia non è che il

frutto di millenarie tecniche di conservazione

dei cibi. Conservare per superare il tempo:

affumicare e ghiacciare, coprire di pepe o di

grasso, saturare di olio, sale, aceto, zuccheri.

Un mondo di saperi e di sapori cui

dobbiamo le infinite sfumature dei formaggi,

le mille forme dei salumi, salamoie e

confetture. Confettare, ovvero ricoprire con

uno strato di zucchero. È solo nel

Cinquecento che lo zucchero in arrivo dalle

colonie sostituisce progressivamente il ruolo

del miele. Candido e luminoso, lo zucchero

è usato per ammantare di grazia la frutta

secca: il confetto prende il posto del

caramello, diventando dolce delle feste e

delle cerimonie. Ma trasformare il buono in

bello è merito del confetto di Sulmona, dal

1800 immutato e immutabile. Levigato,

opalescente, elegantissimo, il confetto

trasfigura una mandorla in un volume puro

e perfetto. Puro come dovrebbe essere un

battesimo o un matrimonio. Tutt’al più tinto

da un’ombra di luminoso colore.