Arbre Magique®, 1951

More than a gadget, l’Arbre Magique®

(originally Little Trees®) is an authentic

popular icon. A Canadian businessman of

Swiss origin, Julius Sämann invents this little

cellulose punch-out drenched in perfumed

essence in 1951. It is destined to conquer

drivers across the world. Hanging from the

rearview mirror and always swinging on the

edge of kitsch, l’Arbre Magique® has now

duly entered in the pantheon of

contemporary iconography, a nostalgic

memory of the carefree 1950s.

Arbre Magique®, 1951

Più che un gadget, l’Arbre Magique® (in

originale Little Trees®) è un’autentica icona

popolare. Fu l’uomo d’affari canadese di

origine svizzera Julius Sämann ad inventare

nel 1951 quella piccola fustella in cellulosa

impregnata con un’essenza profumata e

destinata a conquistare gli automobilisti

di mezzo mondo. Appeso allo specchietto

retrovisore e sempre sospeso sul limite del

kitch, l’Arbre Magique® è oramai entrato

di diritto nel pantheon dell’iconografia

contemporanea, nostalgico ricordo degli

spensierati anni Cinquanta.

Bombay Sapphire Gin, 1761

Legend has it that behind the perfumed

fragrance of Bombay Sapphire Gin, there

is a secret recipe dating to 1761. But this

liquor’s real secret of success is its sapphire

colored bottle, so luminous and transparent.

The magic of its color united with the whiff

of Asian spices evokes the atmosphere of

colonial India, the Bengal Lancers and the

tigers of Nepal. All of this is in a beveled

bottle and a Martini glass.

Gin Bombay Sapphire, 1761

Narra la leggenda che dietro alla profumata

fragranza del Gin Bombay Sapphire ci sia

una ricetta segreta che risale al 1761.

Ma il vero segreto del successo di questo

liquore è la sua bottiglia color zaffiro,

luminosa e trasparente. La magia del colore

unita al sentore di spezie orientali rievoca

le atmosfere dell’India coloniale, i lanceri

del Bengala, le tigri di Mompracem. Tutto

questo in una bottiglia tagliata a ‘baguette’

e in un bicchiere di Martini.

Herman Miller/Vitra Panton Chair,

Verner Panton 1959/1967

“I am not especially interested in shapes.

I usually work through ideas or concepts . . .

A form is open to infinite variations, an idea

isn’t. This is why a concept and a shape are

not the same thing.” Despite these

statements, Verner Panton has to shape the

form of a concept literally with his hands,

in this monolithic chair. Made of a single

material, with no interruptions or joints.

His chair is a true icon, a gesture, a sign that

embodies a turning point that is not only

formal but cultural as well. After leaving the

heroic phase of modernity behind, objects

now just remain images and they perform

an esthetic-narrative role to begin with.

These are things to look at and show before

you use them.

Panton Chair Herman Miller/Vitra,

Verner Panton 1959/1967

“Non sono particolarmente interessato

alle forme. Di solito lavoro per idee o per

concetti … Una forma è aperta ad infinite

variazioni, un’idea no. Per questo un

concetto ed una forma non sono la stessa

cosa”. Eppure, a dispetto di queste

affermazioni, Verner Panton dovette

letteralmente modellare con le sue mani la

forma di un concetto come quello di una

sedia monolitica, realizzata con un solo

materiale, senza stacchi e senza giunture.

La sedia è un’autentica icona, un gesto, un

segno in cui si riassume una svolta non solo

formale ma culturale: superata la fase eroica

della modernità, gli oggetti oramai sono

immagini e svolgono prima di tutto una

funzione estetico – narrativa: cose da

guardare e da mostrare prima che da usare.

111

110

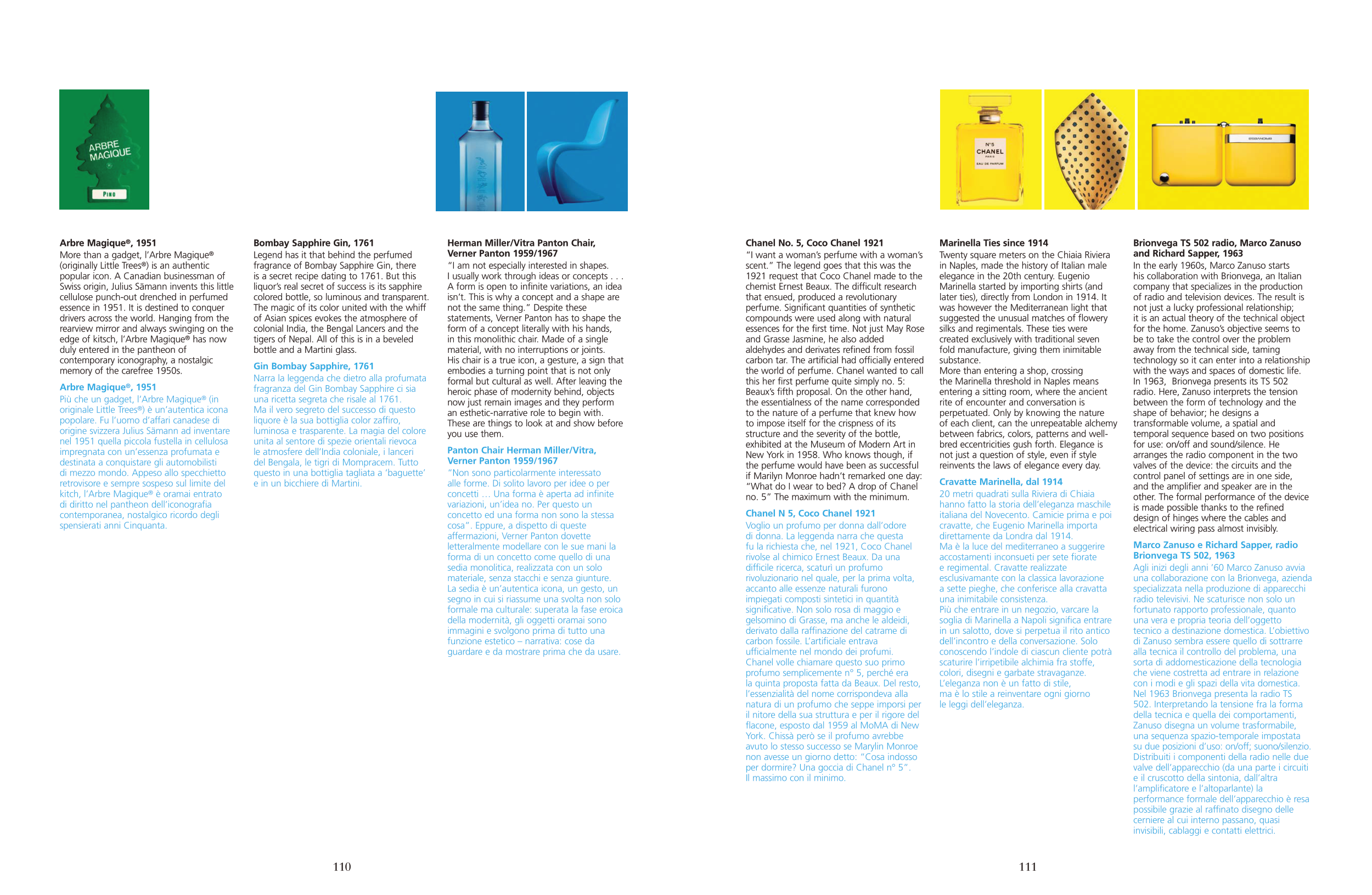

Chanel No. 5, Coco Chanel 1921

“I want a woman’s perfume with a woman’s

scent.” The legend goes that this was the

1921 request that Coco Chanel made to the

chemist Ernest Beaux. The difficult research

that ensued, produced a revolutionary

perfume. Significant quantities of synthetic

compounds were used along with natural

essences for the first time. Not just May Rose

and Grasse Jasmine, he also added

aldehydes and derivates refined from fossil

carbon tar. The artificial had officially entered

the world of perfume. Chanel wanted to call

this her first perfume quite simply no. 5:

Beaux’s fifth proposal. On the other hand,

the essentialness of the name corresponded

to the nature of a perfume that knew how

to impose itself for the crispness of its

structure and the severity of the bottle,

exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art in

New York in 1958. Who knows though, if

the perfume would have been as successful

if Marilyn Monroe hadn’t remarked one day:

“What do I wear to bed? A drop of Chanel

no. 5” The maximum with the minimum.

Chanel N 5, Coco Chanel 1921

Voglio un profumo per donna dall’odore

di donna. La leggenda narra che questa

fu la richiesta che, nel 1921, Coco Chanel

rivolse al chimico Ernest Beaux. Da una

difficile ricerca, scaturì un profumo

rivoluzionario nel quale, per la prima volta,

accanto alle essenze naturali furono

impiegati composti sintetici in quantità

significative. Non solo rosa di maggio e

gelsomino di Grasse, ma anche le aldeidi,

derivato dalla raffinazione del catrame di

carbon fossile. L’artificiale entrava

ufficialmente nel mondo dei profumi.

Chanel volle chiamare questo suo primo

profumo semplicemente n° 5, perché era

la quinta proposta fatta da Beaux. Del resto,

l’essenzialità del nome corrispondeva alla

natura di un profumo che seppe imporsi per

il nitore della sua struttura e per il rigore del

flacone, esposto dal 1959 al MoMA di New

York. Chissà però se il profumo avrebbe

avuto lo stesso successo se Marylin Monroe

non avesse un giorno detto: “Cosa indosso

per dormire? Una goccia di Chanel n° 5”.

Il massimo con il minimo.

Marinella Ties since 1914

Twenty square meters on the Chiaia Riviera

in Naples, made the history of Italian male

elegance in the 20th century. Eugenio

Marinella started by importing shirts (and

later ties), directly from London in 1914. It

was however the Mediterranean light that

suggested the unusual matches of flowery

silks and regimentals. These ties were

created exclusively with traditional seven

fold manufacture, giving them inimitable

substance.

More than entering a shop, crossing

the Marinella threshold in Naples means

entering a sitting room, where the ancient

rite of encounter and conversation is

perpetuated. Only by knowing the nature

of each client, can the unrepeatable alchemy

between fabrics, colors, patterns and well-

bred eccentricities gush forth. Elegance is

not just a question of style, even if style

reinvents the laws of elegance every day.

Cravatte Marinella, dal 1914

20 metri quadrati sulla Riviera di Chiaia

hanno fatto la storia dell’eleganza maschile

italiana del Novecento. Camicie prima e poi

cravatte, che Eugenio Marinella importa

direttamente da Londra dal 1914.

Ma è la luce del mediterraneo a suggerire

accostamenti inconsueti per sete fiorate

e regimental. Cravatte realizzate

esclusivamante con la classica lavorazione

a sette pieghe, che conferisce alla cravatta

una inimitabile consistenza.

Più che entrare in un negozio, varcare la

soglia di Marinella a Napoli significa entrare

in un salotto, dove si perpetua il rito antico

dell’incontro e della conversazione. Solo

conoscendo l’indole di ciascun cliente potrà

scaturire l’irripetibile alchimia fra stoffe,

colori, disegni e garbate stravaganze.

L’eleganza non è un fatto di stile,

ma è lo stile a reinventare ogni giorno

le leggi dell’eleganza.

Brionvega TS 502 radio, Marco Zanuso

and Richard Sapper, 1963

In the early 1960s, Marco Zanuso starts

his collaboration with Brionvega, an Italian

company that specializes in the production

of radio and television devices. The result is

not just a lucky professional relationship;

it is an actual theory of the technical object

for the home. Zanuso’s objective seems to

be to take the control over the problem

away from the technical side, taming

technology so it can enter into a relationship

with the ways and spaces of domestic life.

In 1963, Brionvega presents its TS 502

radio. Here, Zanuso interprets the tension

between the form of technology and the

shape of behavior; he designs a

transformable volume, a spatial and

temporal sequence based on two positions

for use: on/off and sound/silence. He

arranges the radio component in the two

valves of the device: the circuits and the

control panel of settings are in one side,

and the amplifier and speaker are in the

other. The formal performance of the device

is made possible thanks to the refined

design of hinges where the cables and

electrical wiring pass almost invisibly.

Marco Zanuso e Richard Sapper, radio

Brionvega TS 502, 1963

Agli inizi degli anni ’60 Marco Zanuso avvia

una collaborazione con la Brionvega, azienda

specializzata nella produzione di apparecchi

radio televisivi. Ne scaturisce non solo un

fortunato rapporto professionale, quanto

una vera e propria teoria dell’oggetto

tecnico a destinazione domestica. L’obiettivo

di Zanuso sembra essere quello di sottrarre

alla tecnica il controllo del problema, una

sorta di addomesticazione della tecnologia

che viene costretta ad entrare in relazione

con i modi e gli spazi della vita domestica.

Nel 1963 Brionvega presenta la radio TS

502. Interpretando la tensione fra la forma

della tecnica e quella dei comportamenti,

Zanuso disegna un volume trasformabile,

una sequenza spazio-temporale impostata

su due posizioni d’uso: on/off; suono/silenzio.

Distribuiti i componenti della radio nelle due

valve dell’apparecchio (da una parte i circuiti

e il cruscotto della sintonia, dall’altra

l’amplificatore e l’altoparlante) la

performance formale dell’apparecchio è resa

possibile grazie al raffinato disegno delle

cerniere al cui interno passano, quasi

invisibili, cablaggi e contatti elettrici.